Trail of Tears 1839. Painting: “Forced Move” by Max Standley courtesy R. Michelson Galleries.

In her book A Century of Dishonor, published in 1881, Helen Hunt Jackson wrote, “There will come a time in the remote future when, to the student of American history [the Cherokee removal] will seem well-nigh incredible.”

The events leading up to the infamous Trail of Tears, when U.S. soldiers marched Cherokee Indians at bayonet-point almost a thousand miles from Georgia to Oklahoma, offer a window into the nature of U.S. expansion — in the early 19th century, but also throughout this country’s history.

The story of the Cherokees’ uprooting may seem “well-nigh incredible” today, but it shares important characteristics with much of U.S. foreign policy: economic interests paramount, race as a key factor, legality flaunted, the use of violence to enforce U.S. will, a language of justification thick with democratic and humanitarian platitudes. The U.S. war with Mexico, the Spanish-American War, Vietnam, support of the Contras in Nicaragua, the Gulf War, and the invasion and occupation of Iraq come readily to mind. These are my conclusions; they needn’t be my students’. Our task as teachers is not to tell young people what to think but to equip them to search for patterns throughout history, patterns that continue into our own time.

Waynetta Lawrie, left, of Tulsa, Okla., stands with others at the state Capitol in Oklahoma City, in March 2007, during a demonstration by Cherokee Freedmen and their supporters. Source: Associated Press

The Cherokees were not the only Indigenous people affected by the Indian Removal law and the decade of dispossession that followed.

The Seminoles, living in Florida, were another group targeted for resettlement. For years, they had lived side by side with people of African ancestry, most of whom were escaped slaves or descendants of escaped slaves. Indeed, the Seminoles and Africans living with each other were not two distinct peoples. Their inclusion in this role play allows students to explore further causes for Indian removal, to see ways in which slavery was an important consideration motivating the U.S. government’s hoped-for final solution to the supposed Indian problem. Download to read in full.

One pedagogical note. Recently, there has been much discussion — and controversy — about role plays. It’s a term that embraces strategies the Zinn Education Project supports, and others we oppose. Some school activities — “role plays” — demand that students “recreate traumatic experiences,” in the words of Hasan Kwame Jeffries, The Ohio State University professor. No Zinn Education Project activity engages in this kind of teaching. In this and other ZEP role plays, we do not ask students to perform. Although the role play deals with issues of enslavement, theft, and violent dispossession, students do not act any of this out in this role play. Instead, the role play asks students to attempt to represent different individuals’ and social groups’ points of view, to surface underlying motives and objectives. The “drama” in this activity is sparked by the intellectual and ethical questions students discuss, not by reenacting historical events. Read more in “How to — and How Not to — Teach Role Plays.”

Classroom Stories

I have used several interactive lessons from the Zinn Education Project, but one that has stood out the most this year has been the Cherokee Seminole Removal Role Play.

In this lesson, the students stepped back to 1830 and were challenged to take on roles of five groups deeply conflicted over the Congressional bill to implement President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. Putting their own biases aside they were expected to argue the position from groups such as a Northern missionary, a Black Seminole, and a Southern plantation owner. Students gained not online history content knowledge but an understanding of the complexity of the situation and how economic gains perpetuate our country’s institutionalized racism and public policy.

The author of this activity, Bill Bigelow, always consistently crafts interactive lessons that are both rigorous and engaging, and the Cherokee Seminole Removal Role Play is no different. The teacher portion includes thorough background information to prep the students, essential questions and instructions regarding the logistics of transitioning students between the different group tasks.

The role play is a powerful and relevant lesson that has become a mainstay of my U.S. history curriculum and is one that my students described as one of their favorite activities of the year.

The Cherokee/Seminole Removal Role Play enabled my students to put themselves in the shoes of the oppressed (Cherokees and Seminoles) and to demonstrate and defend their position of maintaining their homeland despite broken government treaties. It pitted minority groups against government bigwigs in a courtroom setting.

It tested a biased, “democratic” process we still face today. The results were awesome! Never, and I mean NEVER before have I witnessed such engagement in students during my 18 years in the classroom. The visiting principal and our own principal each spoke to the class. They were in awe! They invited us to their school to demonstrate the ability of complete student interaction. It was a very proud day for all.

I have used the role play of the Indian Removal Act. . . It is so powerful!

100 times better than History Alive which barely addresses the affects on Native Americans.

Students went deep into comparing our watered down textbooks to the dynamic social justice perspective of the Zinn curriculum. They are very critical thinkers — they wondered why our textbook doesn’t go in depth on the affects this had on Native Americans, or how the decisions of rich white men have affected the development of our country.

As an 8th grade Social Studies and U.S. History teacher in Hartford, I proudly used the Zinn Education Project to connect with my students and teach them the history of the U.S. through their own eyes. The eyes of immigrants, workers, and non-paid workers. Each time we used a lesson in class students became more engaged and began to view history through new and different perspectives. They wanted to learn more, to read more, to write more because they connected with the content.

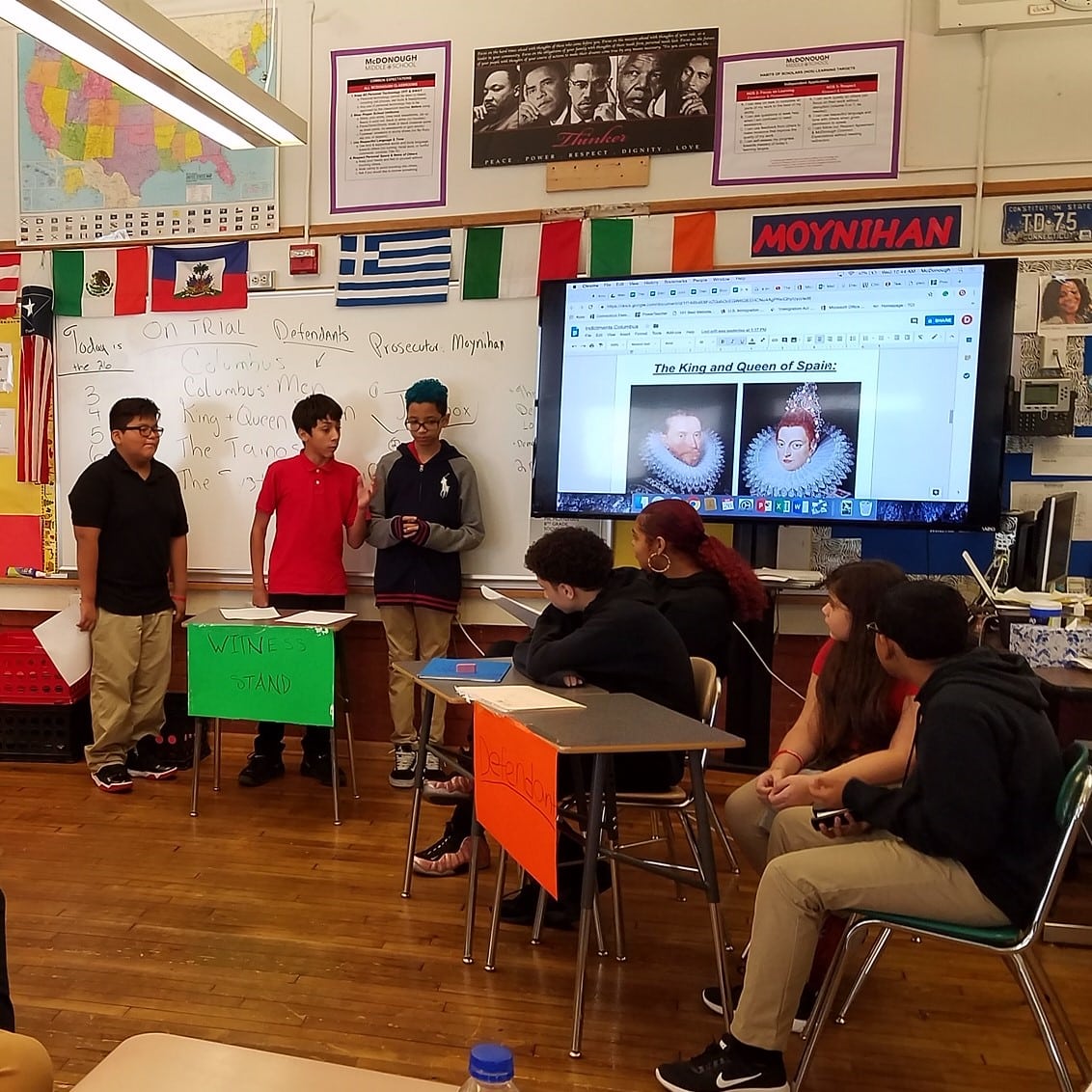

In the Trial of Columbus students learned the real and true story of Columbus’ first landing. Many of my Latino students had heard of the Tainos, the native people of Hispaniola, but they never ever studied about them, now they were into it! During the Cherokee/Seminole Role Play students learned about groups of people that they never knew existed in our country, like the Black Seminoles and the Missionaries and Northern Reformers, and of course Andrew Jackson.

The Zinn Education Project is “what democracy looks like.” It is no surprise that the current Presidential Administration is seeking to destroy it, they are in the process of destroying our democracy and the values which our country was founded on and my students learned about.

Thank you to the Zinn Education Project for helping me reach my students and engage them in learning about the factual history of the United States of America.

I used the lesson about the Indian Removal Act that led to the forced removal of Cherokee Indians and the Trail of Tears. It was the most engaged I had seen my 9th graders in a while. They actively wanted to learn more about the proposed law, how it would affect different groups, and the relative amounts of power different groups held. They argued and negotiated their way through the simulation, absorbing the information and practicing their negotiation and writing skills. In short, it was awesome.

The last two days of the unit culminated in a role play activity from the Zinn Education Project website titled The Cherokee/Seminole Removal Role Play. I love this website. I have previously explained the reaction that the reading passages had on my students and their genuine interest in Zinn’s text. The role play activity from the website took the learning to a new level.

The discussions during the “Congressional Hearing” were lively to say the least. My reward was seeing my students engaged in their own learning throughout the unit thanks to the readings from A People’s History of the United States and the Zinn Education Project website.

I knew I achieved nirvana not only when my principal acknowledged the great job I did, but also when Chuck, the colleague next door who had presented me with Zinn’s book early in the year, came into my classroom to shake my classroom to shake my hands and said to me, “Congratulations, you have taught a great classroom. Your students came into my classroom and couldn’t stop speaking about their roles. They were still arguing against each other and finally I had to say, ‘Enough social studies already!’ You did a great job.” I was beaming and I think I still am.

Originally published by Teaching for Change in Beyond Heroes and Holidays: A Practical Guide to K-12 Multicultural, Anti-Racist Education and Staff Development.

How about something on the Nez Perce Trail ‘of tears’? It’s also known as the Nez Perce War. You all know about Chief Joseph and his famous speech, “I will fight no more forever.” Well that’s where it comes from.

With the Indian Removal Act I guided the students through understanding their role, read primary sources, then students created questions, using evidence from the role cards and primary sources, in order to ask the other groups. We then held a mock congressional hearing in which Jackson and his administration were able to ask and answer questions in regards to the Indian Removal Act. All students got into character really well, gave their reasoning on why Natives should be moved or why they should stay. This lesson really allowed students to see the different perspectives concerning this event. They were also able to justify their decisions with evidence. —Venessa Urioste, high school social studies teacher, Albuquerque, NM

Students dove into the work with a fervency, really taking the issues to heart. —Douglas Tyson, middle school social studies teacher, Ridley Park, PA

I have used this lesson for two years now and it has really made the event come to life and has students wanting to learn more. Many of my students begin to ask if we can do more “things like this” after this lesson. The lesson engages students in real life events that can be tied to the present which is difficult but important as a U.S. history teacher. The discourse after the simulation also provides students with a better understanding of other topics in history such as the civil rights movement and civil war. After teaching this lesson I implemented more Zinn Education Project activities which has really helped my students understand complex ideas and has engaged them more in the study of American history.” —Pate Thomas, high school social studies teacher, Las Vegas, NV

I modified the trial into a larger unit of historical thinking. Students were given the role of investigative journalists or detectives building a case for/against Andrew Jackson or the United States in general (this wasn’t only Jackson that railed against Indians).

We used primary sources including:

1. Elias Boudinot’s letter to Cherokee in 1837 (Stanford’s Reading Like a Historian lesson on Indian Removal)

2. Jackson’s speeches in 1830 (January & December) to congress.

3. Worcester vs Georgia Supreme Court case

4. Supporting and Opposing viewpoints from congressmen of the time (Lewis Cass, Sec of War for Jackson, Theodore Frelinghuysen,

5. Propaganda – Andrew Jackson as “The Great Father” painting, “Hunting Indians in Florida with Bloodhounds”

6. Past/Future president’s remarks about Native American removal – Washington, Jefferson, Monroe, Jackson, Van Buren, Taylor, etc

Then congress had their hearings (instead of the trial) in 1840 so the different interest groups could have hindsight to all the events as they presented their case for/against removal. Congress also had to look up actual congressmen from the 26th congress (1840) and take on that role during the hearings.

I’d love any additional resources people have found regarding primary sources and the 5 roles used in this simulation. I’d like to give students the option of additional sources to use and have found some good sources (text on treaties, some speeches by Congressmen both for/against, etc). I’m really needing some additional sources for Black Seminoles, Missionaries, and Southern Planters. If anyone has any sources (particularly online!) I’d be very grateful! Kate Harrigan (8th Grade teacher)