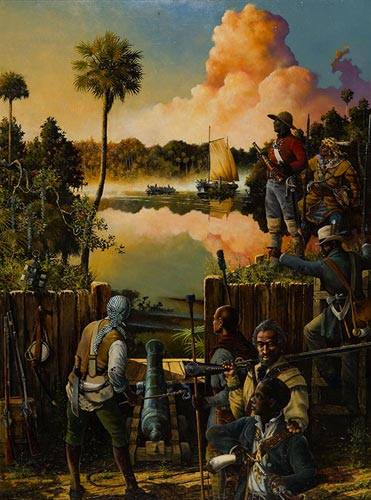

Attack on Apalachicola River. The fort had provided home and safety to more than 300 African and Choctaw families. Painting by Jackson Walker, Museum of Florida Art.

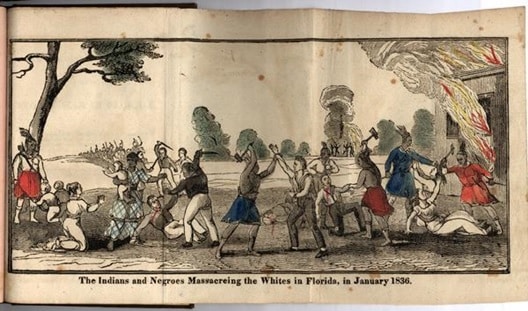

Colonial laws prohibiting Black and white people from marrying one another suggest that some Black and white people did marry. Laws imposing penalties on white indentured servants and enslaved Africans who ran away together likewise suggest that whites and Blacks did run away together. Laws making it a crime for Indians and Black people to meet together in groups of four or more indicate that, at some point, these gatherings must have occurred. As Benjamin Franklin is said to have remarked in the Constitutional Convention, “One doesn’t make laws to prevent the sheep from planning insurrection,” because this has never occurred, nor will it occur.

The social elites of early America sought to manufacture racial divisions. Men of property and privilege were in the minority; they needed mechanisms to divide people who, in concert, might threaten the status quo.

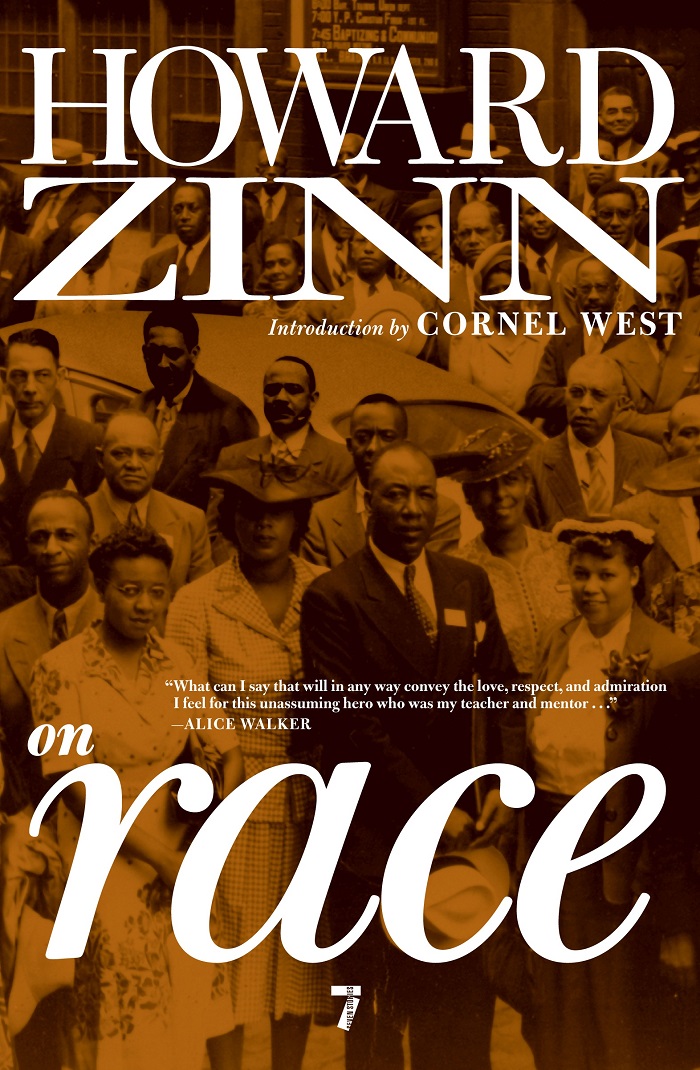

Individuals’ different skin colors were not sufficient to keep these people apart if they came to see their interests in common. Which is not to say that racism was merely a ruling class plot, but as Howard Zinn points out in chapters 2 and 3 of A People’s History of the United States, and as students see in this lesson, some people did indeed set out consciously to promote divisions based on race.

Because today’s racial divisions run so deep and can seem so normal, providing students an historical framework can be enlightening. We need to ask, “What are the origins of racial conflict?” and “Who benefits from these deep antagonisms?” A critical perspective on race and racism is as important as anything students will take away from a U.S. history course. This is just one early lesson in our quest to construct that critical perspective.

Classroom Stories

The Color Line lesson is one of my all-time favorite middle-school social studies lessons.

It gets to the heart of a core issue in U.S. history and contemporary politics: “divide and conquer” tactics, which elites use to maintain power and control. The lesson asks students to put themselves in the minds of the elites and brainstorm laws to prevent oppressed groups from joining together. It refers to primary source texts in a meaningful, accessible way.

If I just had one hour to teach all of U.S. History, I’d probably choose this lesson.

The Color Line lesson led to a discussion about how oligarchs defend their interests. We would come back to that throughout the school year because the students noticed how race was being used as a wedge issue again and again. . .

The Color Line lesson led to a discussion about how oligarchs defend their interests. We would come back to that throughout the school year because the students noticed how race was being used as a wedge issue again and again. . .

When students learned how race had been created, how the structure of white supremacy had been constructed, they began to realize that it could also be destroyed.

— Julian Hipkins III

High School U.S. History Teacher, Washington, D.C.

Originally quoted in “How American oligarchs created the concept of race to divide and conquer the poor” by Courtland Milloy in The Washington Post.

I had my students read chapter 2, then create board games where they made up laws that would “Divide and Conquer.” After playing the games, we took a look at actual laws to see if the students or the colonists were the most brutal.

I asked my students to create a timeline of slavery using Zinn’s chapter 2 and asked at least three questions so that they could use the timeline and online further research to answer these questions.

I have my students write an essay on how slavery changed from black and white to only black and use Howard Zinn’s Chapter 2 and 3 as supporting evidence. My students are always amazed at the origins of racism in North America. – Miroslaba Velo