Textbooks and state curricula devote little attention to the abolition movement, let alone to Black abolitionists. To counter the invisibility of Black abolitionists who were central to the abolition movement and the ending of slavery, we feature two dozen Black abolitionists here. This collection is not comprehensive, indeed there are many more Black abolitionists who fought against slavery, assisted people in the Underground Railroad, or supported the movement in a myriad of ways. Learn more about the abolition movement, outside the textbook, in the lesson, “‘If There Is No Struggle . . .’: Teaching a People’s History of the Abolition Movement.”

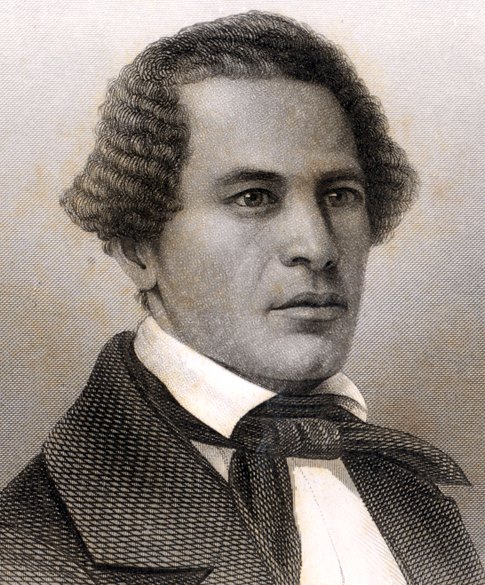

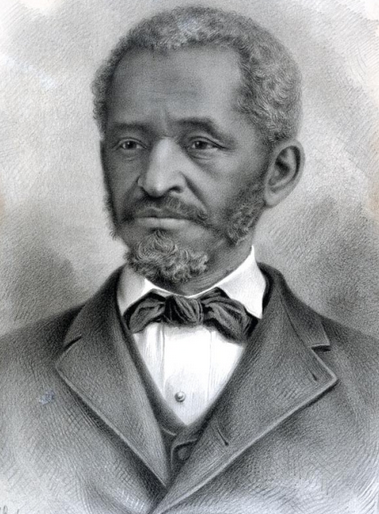

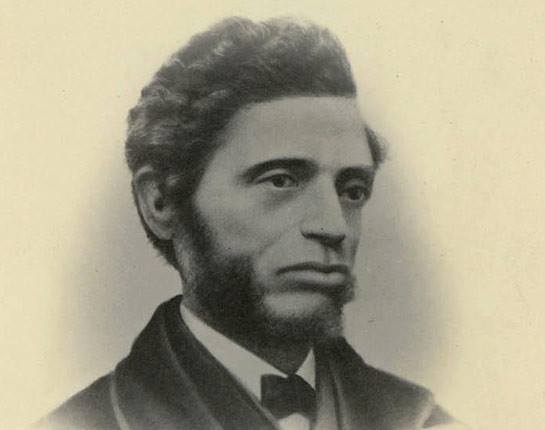

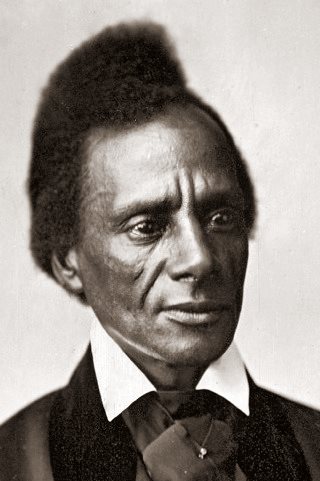

Engraving by John Chester Buttre. Source: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College |

William Wells BrownWilliam Wells Brown was born in bondage in 1814. Much of his childhood was spent working in St. Louis, Missouri. In one of his numerous attempts to escape, he and his mother were caught. She was shipped south to New Orleans and he never saw her again. Brown was finally able to escape on New Year’s Day in 1834. He went to Buffalo, NY, where he worked on steamboats and assisted in the work of the Underground Railroad. In the 1840s, Brown joined the abolitionist movement, attending conventions, working on committees, and giving speeches. In 1847 he was hired by the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society as a public speaker and moved to Boston. That same year he published his “Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave,” which was widely read and revered. Due to the threat of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, he went to England for five years. After the end of the Civil War, Brown continued to write, publishing three volumes on Black history, a novel, travelogues, a play, and a collection of abolitionist songs. Before Brown passed away in 1884, he was regarded as the foremost Black writer in the United States. He also became a physician. Learn more at the State Historical Society of Missouri. |

Paul CuffeeNo Taxation Without Representation! On Feb. 10, 1780, Paul Cuffee and others petitioned the Massachusetts government either to give African and Native Americans the right to vote or to stop taxing them. The petition was denied, but the case helped pave the way for the 1783 Massachusetts Constitution, which gave equal rights and privileges to all (male) citizens of the state. Here is an excerpt from the transcript of the petition submitted to the Mass. legislature: To the Honorable Council and House of Representatives, in General Court assembled, for the State of the Massachusetts Bay, in New England: The petition of several poor negroes and mulattoes, who are inhabitants of the town of Dartmouth, humbly showeth,—That we being chiefly of the African extract, and by reason of long bondage and hard slavery, we have been deprived of enjoying the profits of our labor or the advantage of inheriting estates from our parents, as our neighbors the white people do, having some of us not long enjoyed our own freedom; yet of late, contrary to the invariable custom and practice of the country, we have been, and now are, taxed both in our polls and that small pittance of estate which, through much hard labor and industry, we have got together to sustain ourselves and families withall. . . . Written by hand is: This is the copy of the petition which we did deliver unto the Honorable Council and House, for relief from taxation in the days of our distress. But we received none. JOHN CUFFE. Read more on Infoplease.com. Read more about Cuffee on BlackPast.org. |

|

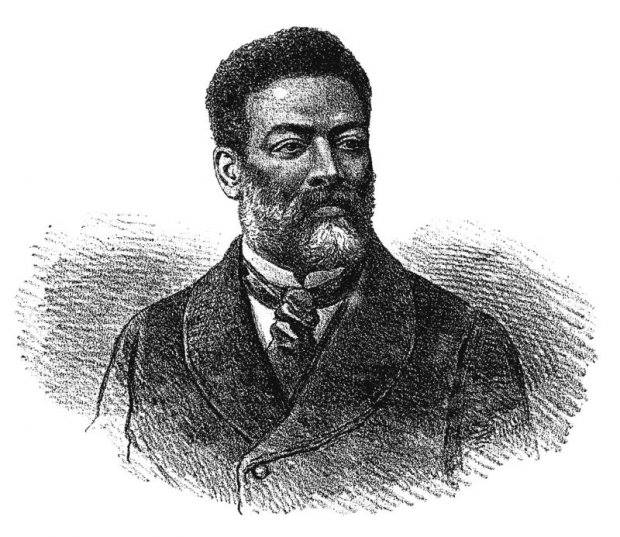

Luís GamaLuís Gama (June 21, 1830—August 24, 1882) abolitionist, journalist, lawyer, and poet. Gama was born in Salvador, Brazil in 1830, his biological father a wealthy Portuguese man and his mother, Luisa Mahin, a revolutionary Black woman from Ghana. Mahin played a major role in a number of slave uprisings, including the Malê Revolt. At the age of 10, Gama’s father sold him into slavery. In 1848, Gama escaped his enslavement and was able to win his legal freedom after proving to a court that he was born free. As noted on the AfroEurope International blog, “Gama published a collection of poems, mocking Pardos (mixed race) who wanted to be white and sold out their Black brother and sisters by denying their roots so they could join the elite.” Gama gained a reputation in Brazil as a Rabula, or a lawyer without a law degree who represented people who were enslaved against their “masters.” By the end of his life, he had helped to free upwards of 1,000 enslaved people and become one of Brazil’s most prominent abolitionists and revolutionaries. Read much more about Gama’s life at the AfroEurope International blog.

|

|

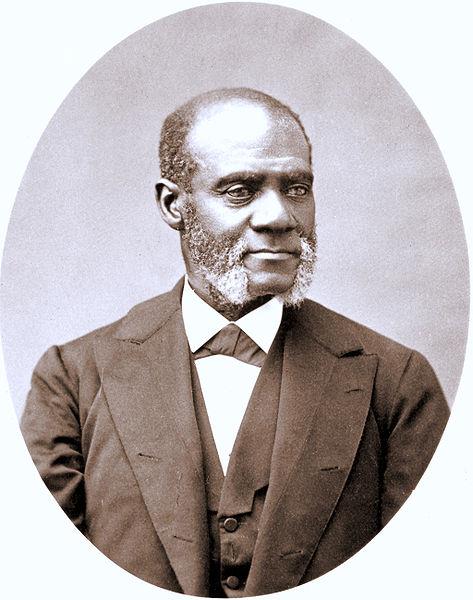

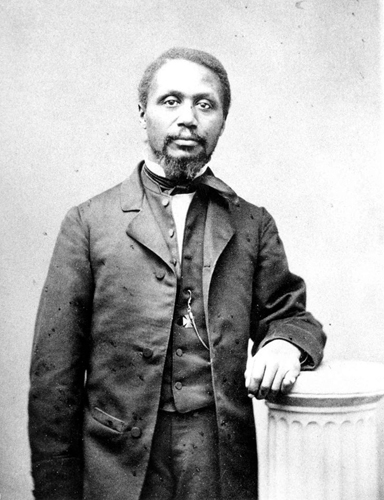

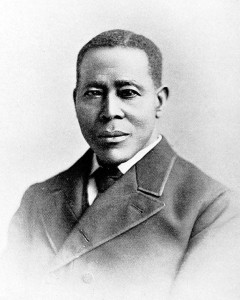

William Howard DayAttorney, newspaper editor, minister, and abolitionist William Howard Day traveled to Britain in 1859 where he lobbied for a boycott of cotton from the U.S. to break the economic profitability of human bondage. Read a report on those talks from the Black Abolitionist Archive. On July 4, 1865, he gave a speech on the White House grounds to thousands of people including African Americans recently freed from bondage, congressmen, and government officials. Day reminded those assembled that “the Declaration of Independence is not yet fully carried out, nor will it be, until . . . the Black man, as well as the white, is permitted to enjoy all the franchises pertaining to citizens of the United States of America.” Day later worked for the Freedmen’s Bureau. Learn more at the Colored Conventions Project.

|

|

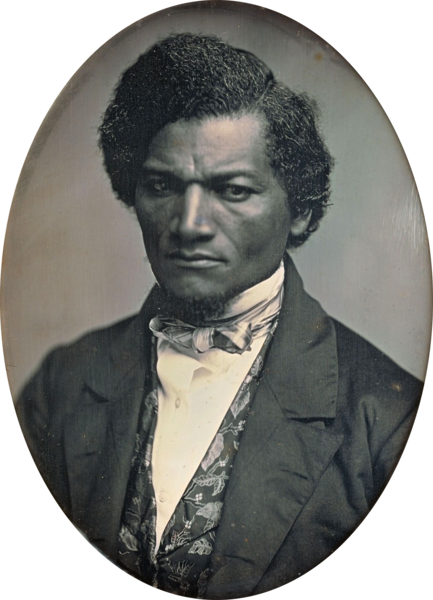

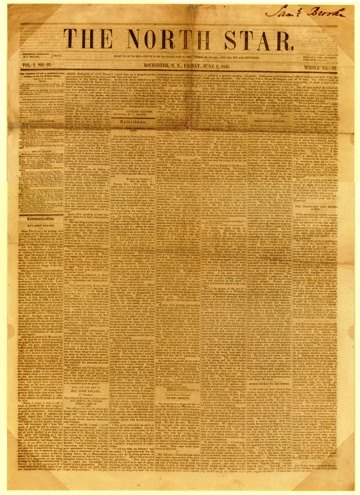

Frederick DouglassFrederick Douglass, abolitionist, orator, writer, newspaperman, and statesman, selected February 14 to mark the day of his birth, 1818. Here is a free downloadable lesson for teaching about Douglass’ fight for freedom and a video clip of Danny Glover reading his July 4 speech. Given the breadth of Douglass’s scholarship and activism, he is also included in other lessons on the Zinn Education Project website such as the role plays on the Seneca Falls Convention and the U.S.-Mexico War, see these and more here.

|

|

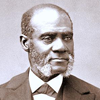

Henry Highland GarnetHenry Highland Garnet was born in captivity in Maryland in 1815. When he was nine, his family secured their freedom via the Underground Railroad. Garnet entered the African Free School in New York City in 1826. In 1834, Garnet and some of his classmates formed their own club, the Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association. Because the society was named after a controversial abolitionist, the public school where the group wanted to meet insisted that the group first change their name. To do otherwise would be to risk mob violence. The club decided to keep their name and instead change their venue. The first meeting of the group garnered over 150 African Americans under 20. Garnet is perhaps most famous for his radical speech of 1843, “An Address to the Slaves of the USA.” In this speech, Garnet speaks directly to those enslaved, urging them to rebel against their masters. Because of Garnet’s outspoken views and national reputation, he was a prime target during the 1863 New York City draft riots. Rioters mobbed the street where Garnet lived and called for him by name. Fortunately several neighbors helped to conceal Garnet and his family. Garnet was also involved in the fight to desegregate streetcars. This description is from The New York African Free School Collection. Read more here and here. Photo from National Portrait Gallery. |

|

Leonard GrimesLeonard Grimes (1815-1873), born in Virginia, was an abolitionist and pastor who played an active role on the Underground Railroad. After witnessing the horrors of slavery as a young man, Grimes determined to do all he could to help people escape. He got a job as a hackman (horses and carriages for hire) to provide cover for his work on the Underground Railroad. In 1839 he was arrested in Washington, D.C. (yes, our nation’s capitol) for transporting a family to freedom and sent to Virginia, where he was sentenced to two years of hard labor in the Richmond penitentiary. After his release, he and his family moved to Boston, where he became the first pastor of Twelfth Baptist Church, known as The Fugitives Church. There he continued his abolitionist work and open defiance of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. He was credited with helping hundreds of freedom seekers make their way to Canada. [Description adapted from Cultural Tourism DC.] We highly recommend this short essay about his life by Deborah A. Lee. |

|

Charlotte Forten GrimkéAbolitionist and educator Charlotte Forten Grimké was the granddaughter of Philadelphia abolitionist James Forten. She was active in the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society. After the start of the Civil War, Forten taught a community of African Americans living on the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina who had been liberated in 1862. She wrote about the experience in her article “Life on the Sea Islands,” published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1864. Read more at BlackPast.org.

|

|

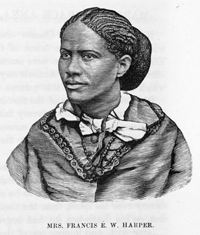

Frances Ellen Watkins HarperFrances Ellen Watkins Harper was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1825. After teaching in Pennsylvania and Ohio for two years, she traveled the U.S. speaking on the abolitionist circuit and assisting in the Underground Railroad. In addition, Harper was a prolific and celebrated writer. Throughout her life she published numerous collections of poetry, including Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects and Sketches of Southern Life. In short time, Harper became the most celebrated female African American writer in the United States. Here is an excerpt from a poem she wrote about slavery: And mothers stood with streaming eyes After the end of the Civil War, Watkins supported the advancement of civil rights for African Americans, women’s rights, and equality in education for all. Read more at the Archives of Maryland and ExplorePAHistory.com. Image source: New York Public Library Digital Gallery. |

|

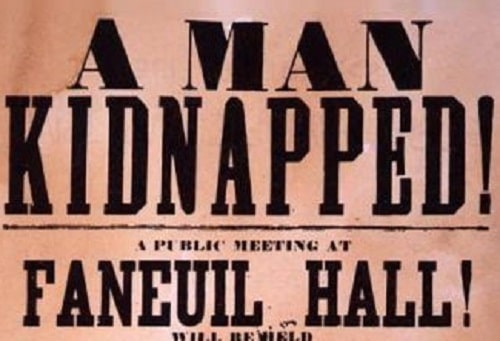

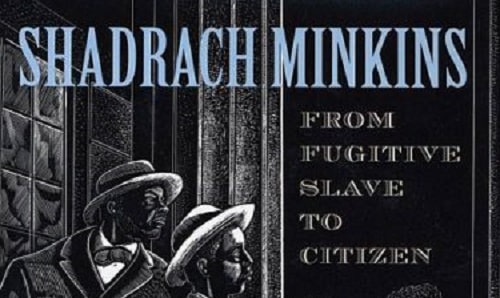

Lewis HaydenLewis Hayden was born in bondage in 1811 in Lexington, Kentucky. His first wife and son were sold by U.S. Senator Henry Clay into the deep south and Hayden never saw them again. He married Harriet Bell in 1840. The couple escaped on the Underground Railroad in 1844, fleeing to Canada before they made their way to Boston. (The two abolitionists who assisted Hayden’s escape were arrested and jailed.) In Massachusetts, Hayden and his family ran a clothing store where they held abolitionist meetings and provided refuge for people escaping from slavery. It was rumored that the Haydens’ stored two kegs of gunpowder in their home in the case that slave catchers would ever attempt to capture the people they sheltered —- they’d have rather blown up the house than surrender the persons they were protecting. Hayden assisted high profile people including Ellen and William Craft, Shadrach Minkins, and Anthony Burns. Additionally, Hayden raised funds for John Brown’s Harper’s Ferry Raid. During the Civil War Hayden helped recruit Black soldiers and later served a term in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He worked for a monument to honor Crispus Attucks and supported women’s suffrage. Hayden passed away in 1889. On Harriet Hayden’s death, she bequeathed funds to form a scholarship for African American students at Harvard Medical School. |

|

Josiah HensonBorn into slavery in 1789 in Maryland, Josiah Henson fled to Canada with his family where he founded the Dawn Institute, a settlement house which taught trades to people who had escaped enslavement. A Methodist preacher, he traveled throughout the United States and Great Britain lecturing against slavery. With the underground railroad he assisted over two hundred people in their flight to Canada. [Description from the National Park Service.] Henson’s description of his experiences, an early slave narrative, served as the basis for the book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Read more about Josiah Henson at the Documenting the American South website. |

|

|

|

Paul JenningsPaul Jennings (1799 – 1874) was held in bondage by President James Madison during and after his White House years. After securing his freedom in 1845, Jennings published the first White House memoir. His book, A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison, is described as “a singular document in the history of slavery and the early American republic.” Read excerpts at Documenting the American South. Jennings also played a lead role in planning the Pearl incident “the largest recorded escape attempted by people from enslavement in U.S. history.” Read more at the Zinn Education Project. |

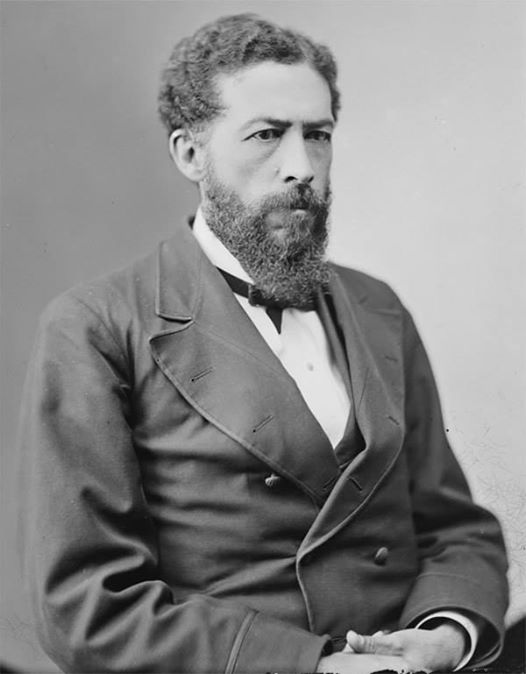

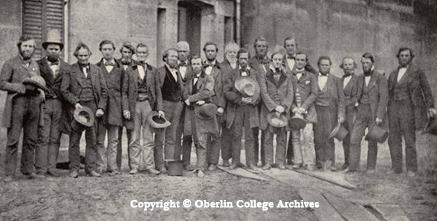

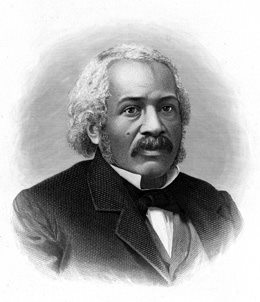

John Mercer Langston“It has been discovered, at last, that slavery is no respecter of persons, that in its far reaching and broad sweep it strikes down alike the freedom of the Black man and the freedom of the white one. This movement can no longer be regarded as a sectional one. . . it must be evident to every one conversant with American affairs that we are now realizing in our national experience the important and solemn truth of history, that the enslavement and degradation of one portion of the population fastens galling festering chains upon the limbs of the other. For a time these chains may be invisible; yet they are iron-linked and strong; and the slave power, becoming strong-handed and defiant, will make them felt.” John Mercer Langston (abolitionist, politician, and attorney) in a speech delivered in August of 1858. Read full speech at the The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue website. Read Langston’s bio at BlackPast.org. Photo from Brady-Handy Collection at the Library of Congress.

|

|

Robert MorrisRobert Morris (June 8, 1823 – Dec. 12, 1882) was one of the first African American lawyers in the United States. He was one of the abolitionists who helped Shadrach Minkins escape from the courthouse on Feb. 15, 1851, where he had been brought under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Morris was tried and acquitted for his role in the Minkins escape. Morris was also one of the attorneys for Benjamin Roberts who filed the first school integration suit on Feb. 15, 1848 (Roberts v. Boston) after Roberts’ daughter Sarah was barred from a white school in Boston, Mass. Read more in the book Sarah’s Long Walk (Beacon Press) and at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Read more about Robert Morris at BlackPast.org and at Boston College Law School. Photo in public domain.

|

|

William Cooper NellWilliam Cooper Nell, African-American abolitionist, journalist, author, and civil servant was born on December 16, 1816. Nell was one of the first people to record extensive African American history (a people’s historian!) and an activist for school desegregation in Boston. Read more on BlackPast.org. |

|

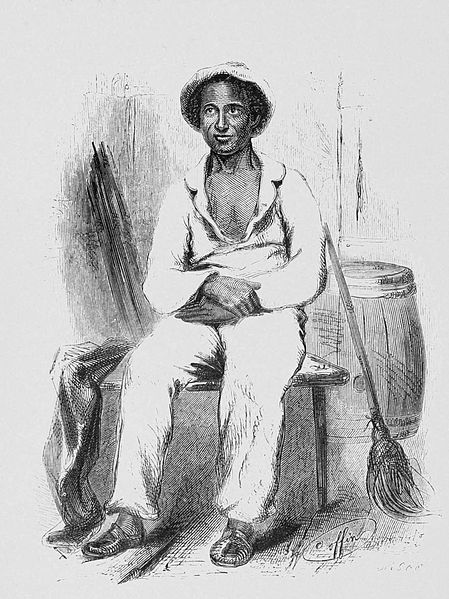

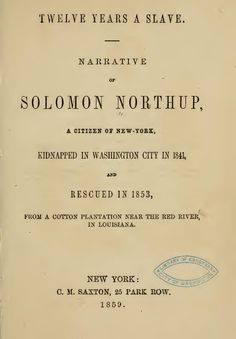

Solomon Northup

Missing from the film was his abolitionist activity after his emancipation. Northup wrote his book to expose the brutal conditions of enslavement and he spoke across the U.S. His campaign for reparations, supported by Frederick Douglass and Free Soil Party U.S. Congressman Gerrit Smith, was a precursor to the national reparations campaign for all African Americans. Read “We Need to Include Reparations in the Story of Solomon Northup.” |

|

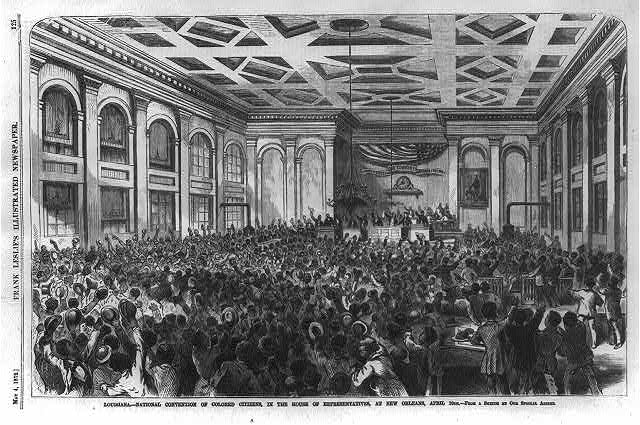

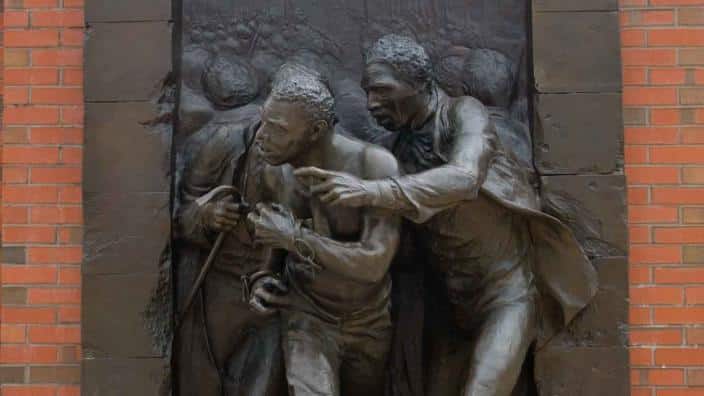

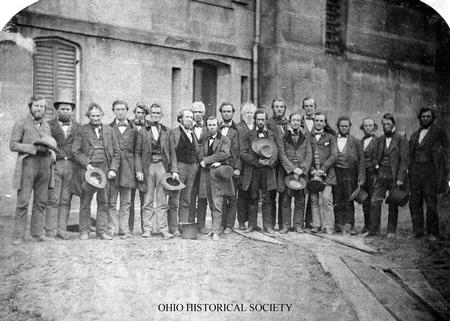

Oberlin-Wellington RescuersOn September 13, 1858, group of the citizens of Oberlin, Ohio, stopped Kentucky “slave-catchers” from kidnapping John Price. Oberlinians, Black and white, from town and from the local College, pursued the kidnappers to nearby Wellington at word of his abduction. Read more about the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue. |

|

Sarah Parker RemondBorn into a family of abolitionists who were also active in the Underground Railroad, Sarah Parker Remond gave her first abolitionist speech at the age of sixteen. This was a radical action at the time not just because she was young and black, but also because she was a woman. Remond was a member of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, in addition to other antislavery organizations. When Remond was 27 she refused to accept segregated seating at an event at Boston’s Howard Athenaeum. While being forcibly removed, Remond was pushed down a flight of stairs by a police officer. After taking the city of Boston to court she was awarded a settlement of $500 in a case that drew national attention. Remond traveled across the country as an abolitionist lecturer and also to England. She eventually moved to Italy and became a physician. Read more at the BlackPast.org. Photo: © Peabody Essex Museum, 1865.

|

|

Charles Lenox RemondCharles Lenox Remond (1810-1873) joined the abolitionist movement while in his early twenties, working as an agent for Garrison’s Liberator in 1832 and later as a lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society. These experiences helped earn him a nomination as the only African American delegate to the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. During this conference and his subsequent United Kingdom lecture circuit, he developed a reputation as an eloquent orator, additionally demonstrating his commitment to women’s rights by protesting the conventions rejection of female delegates. Upon his return to the United States, Remond labored not only to end slavery, but to improve the lives of free-Blacks in the north, lobbying the Massachusetts House of Representatives to end segregation on trains. Biography from the Colored Conventions Project. Read more about Charles Lenox Remond at BlackPast.org. Photo from Boston Public Library.

|

|

David Ruggles“David Ruggles (1810-1849) was an abolitionist, editor, writer, organizer of the New York Committee of Vigilance and famed conductor of the Underground Railroad. He was renown for his unflinching courage in the battle against kidnappers and illicit traders of enslaved people. He was the first Black bookseller and operated the first Black lending library in the nation. His magazine, the Mirror of Liberty, was the first periodical published by an African American. . . . New York’s economy depended directly or indirectly on slavery. Mobs did not hesitate to attack abolitionists, especially one as provocative as Ruggles. His store was burned down three times; he was beaten in jail twice and once nearly kidnapped to be sold into slavery.” Description by Graham Russell Gao Hodges, author of David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York City. Read full interview and learn more about the book at the University of North Carolina Press website. Learn more about his work fighting the police in the Time article, “The Black New Yorker Who Led the Charge Against Police Violence in the 1830s” by Jonathan Daniel Wells.

|

|

Mary Ann ShaddMary Ann Shadd Cary was born in Wilmington, Delaware in 1823 where her parents were abolitionists and their home was a station on the Underground Railroad. They moved to Pennsylvania so that their children could attend school because the education of Black children was illegal in Delaware. Cary studied at a Quaker school and became an educator, teaching for 12 years. After the passage of Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which was a threat to the safety of all African Americans, the Shadds moved to Canada. Cary wrote and published a pamphlet encouraging other Blacks to settle in Canada and founded Canada’s first anti-slavery newspaper, the Provincial Freeman. She supported John Brown’s raid on the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry and helped Osborne P. Anderson publish his firsthand account of the raid. She returned to the U.S. where she became active in the Women’s Suffrage Movement and she studied law at Howard University. After initially being denied access to the bar, she received her law degree in 1883. For more information on Shadd Cary’s life, read here. |

|

William StillFervent abolitionist. William Still was born free in 1821 and was known as the “Father of the Underground Railroad.” Still helped more than 800 people escape slavery and continue on the road to freedom. He also served as chairman of the Vigilance Committee for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. A meticulous record keeper, Still once discovered that he aided in the escape of an older brother who was left behind when their parents escaped slavery.

In 1872, Still published an account of his work on the Underground Railroad in The Underground Railroad Records. A leader in the community, Still also helped to establish an African American orphanage and open the first YMCA for Blacks in Philadelphia. For more information on William Still’s life, read here. |

|

James McCune SmithThe African Free School opened on this day in 1788 in New York for the children of people who were enslaved and free Blacks. By the time it was incorporated into New York Public Schools in 1835, it had educated thousands of people including doctor and abolitionist James McCune Smith. Learn more about the school’s history and see samples of student work in a New York Historical Society online archive. Related resource: New York and Slavery: Time to Teach the Truth by Alan Singer |

|

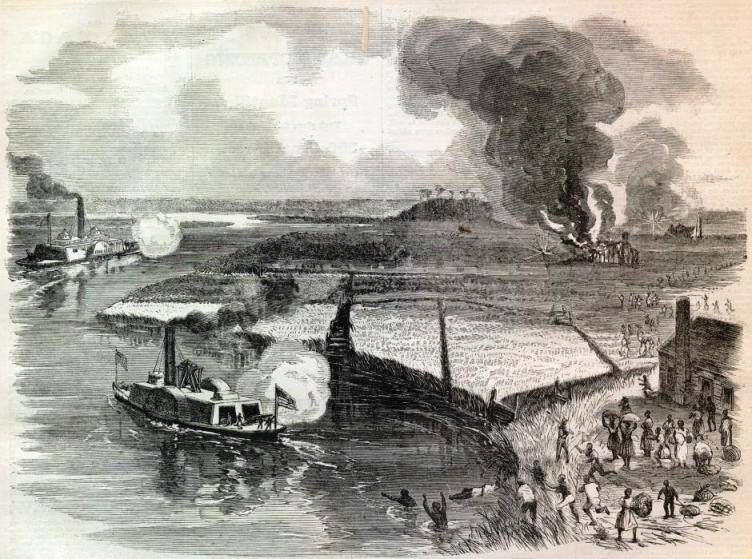

Harriet TubmanPerhaps one of the most famous abolitionists and Underground Railroad operators, Harriet Tubman, was born into slavery in the early 1820s in Dorchester County, Maryland. In 1849 Tubman fled Maryland for the north. She would return south on countless trips to bring people to freedom on the Underground Railroad. Less known is her role during the Civil War when she led the Union army in the Raid at Combahee Ferry that freed more than 700 people from slavery. This was the only Civil War military operation led by a woman and it was extremely successful. Read more here. Later in her life she also became active in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. Read more at BlackPast.org. |

|

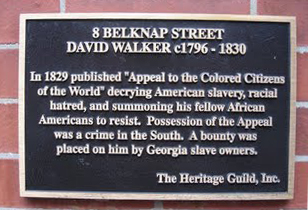

David Walker

At the time, the “Appeal” was the most widely read anti-slavery document in the United States. Walker, with the help of sailors, church leaders, and more was able to smuggle copies of his “Appeal” to plantations in the South. As a result, Walker’s “Appeal” was banned in the South and laws were passed which made it illegal for Blacks to learn how to read. A bounty was put on Walker’s head. In addition to penning the “Appeal,” Walker was a leading abolitionist and noted public speaker in Boston. He wrote and helped support the first African American newspaper, “Freedom’s Journal.” Three editions of Walker’s “Appeal” were published before he passed away in 1830. Learn more at The David Walker Memorial Project. When teaching Walker’s Appeal, it would be important to note that Native Americans were also frequently described with non-human terms such as “beasts” or as “savages.” And the tactic of renaming a group in order to dehumanize and oppress them can be seen in other settings, such as “gooks” in Vietnam. But the wholesale renaming of a people, to the point that even today many refer to “slaves” instead of “people” continues today with reference to enslaved Africans. For example, “slaves brought from Africa” or “George Washington had slaves” when in fact “people were brought in bondage from Africa” and “George Washington ‘owned and sold’ people.” |

|

This article is also available at Newsela. It was adapted for several additional reading levels by Newsela staff in September 2019.

Paul Cuffee

Paul Cuffee

My story of slavery centres around the Seychelles where my family are from so my own personal journey about slavery will start from there and I’m not sure what I will discover when I go back in January 2017.

Thank you for presenting the list of black Abolitionist, I was not aware of these amazing peoples existence. I am now in awe of the depth and breadth of bravery, humanity, courage and intellectual stamina shown by these activist. They took action via the Underground railways and also lobbied the white establishment to try and change hearts and minds. America should honour them and their stories should be part of American folklore.The work you are doing is priceless, thank you so much for preserving our history.

Death, Hatred, Slavery, Racism, Ignorance, Stupidity, Insanity and Madness is Abolished.

WDivinelove

This is fantastic! My students and I are doing a unit on slave narratives in American literature. I wanted to include the experiences of free African Americans and the heroism of African-American abolitionists. Thank you for this invaluable resource.

This is a very useful list. Might I suggest adding Alexander Crummell and Samuel Ringgold Ward?

There are many more Black Abolitionist in the West and Upper Canada. How can we keep growing this wonderful list? ex. Peter H. Clark–Black American Socialist.

Suggest you add John Parker and the Ripley (Ohio) Group. I learned about him at the Freedom Center in Cincinnati, and more from Ann Hagedorn’s Beyond the River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad.(2002). There were substantial interactions among the Ripley line and the people in Oberlin and those involved in the Wellington Rescue.

This is excellent information for young and old. Thank you.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade included the Africans who were taken to the Caribbean. The Abolitionist list is even higher than you think. The people who were on board the Marlborough and Armistad. Toussaint L’Overture, Cuffy, Paul; Bogle, Nanny of the Maroons to name a few.