The impact women have made in labor history is often missing from textbooks and the media despite the numerous roles women have played to organize, unionize, rally, document, and inspire workers to fight for justice. From championing better workplace conditions to cutting back the 12-hour day to demanding equal pay across racial lines, these are just a few of the women who have contributed to the labor movement. Also visit the And Still I Rise website that features Black women labor leaders.

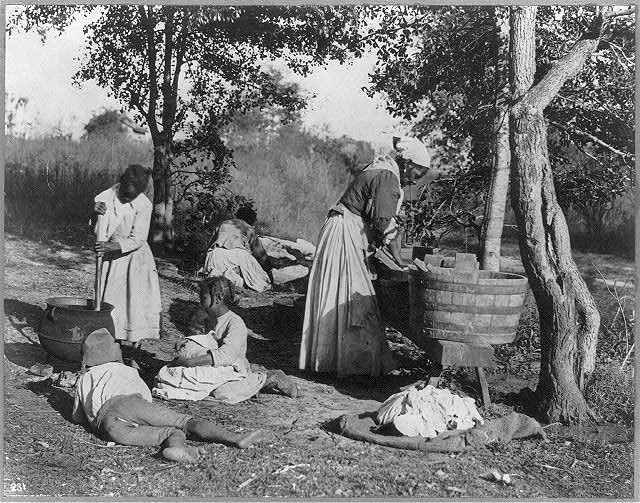

Louise BoylePhotographer Louise Boyle figures prominently among those of her time whose penetrating images documented the devastating effects of the Great Depression on American workers. In 1937, at the height of a wave of labor militancy, Ms. Boyle was invited to photograph the living and working conditions of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union members from several Arkansas communities. Her provocative recording courageous people linking their futures together despite devastating poverty, physical hardship, and brutal police-endorsed reprisals. Most portray African American farmers in their homes, at union meetings and rallies, or at work with their families picking cotton. Boyle returned in 1982 to rephotograph some of the people and places she had documented earlier. [Description by Kheel Center, Cornell University.] See photo collection on Flickr. Find a free lesson on the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union. |

|

Hattie CantyLegendary African-American unionist Hattie Canty migrated to Las Vegas from rural Alabama. In contrast to the AFL-CIO’s George Meany, who bragged that he had never been on a picket line, Canty was one of the greatest strike leaders in U.S. history. Her patient leadership helped knit together a labor union made up of members from 84 nations. “Coming from Alabama,” Canty observed, “this seemed like the civil rights struggle . . . the Labor Movement and the Civil Rights Movement, you cannot separate the two of them.” Read more about Hattie Canty at Online Nevada Encyclopedia.

|

|

|

|

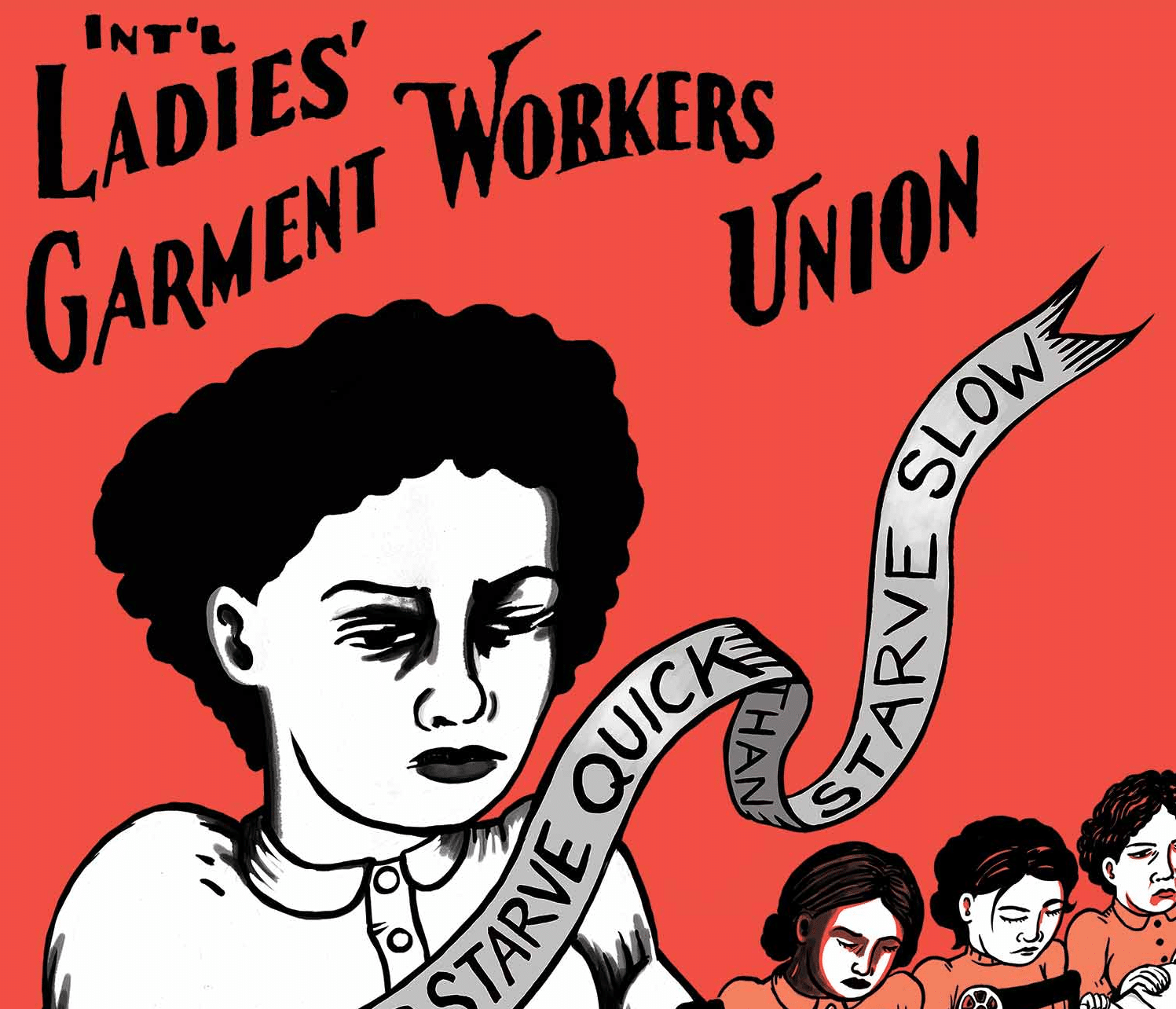

May ChenIn 1982, May Chen led the New York City Chinatown strike of 1982, one of the largest Asian American worker strikes with about 20,000 garment factory workers marching the streets of Lower Manhattan demanding work contracts. Chen, then affiliated with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, was one of the strike organizers. “The Chinatown community then had more and more small garment factories,” she recalled. “And the Chinese employers thought they could play on ethnic loyalties to get the workers to turn away from the union. They were very, very badly mistaken.” Most of the protests included demands for higher wages, improved working conditions and for management to observe the Confucian principles of fairness and respect. By many accounts, the workers won. The strike caused the employers to hold back on wage cuts and withdraw their demand that workers give up their holidays and some benefits. It paved the way for better working conditions such as hiring bilingual staff to interpret for workers and management, initiation of English-language classes and van services for workers. [Description by Cristina DC Pastor, from the Feet in Two Worlds website.] Read more about Asian immigrants in the workforce at the Feet in Two Worlds website. |

Jessie de la CruzOn September 5, 2013, Jessie de la Cruz passed away at age 93. A field worker since the age of five, Jessie knew poverty, harsh working conditions, and the exploitation of Mexicans and all poor people. Her response was to take a stand. She joined the United Farm Workers union in 1965 and, at Cesar Chavez’s request, became its first woman recruiter. She also participated in strikes, helped ban the crippling short-handle hoe, became a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, testified before the Senate, and met with the Pope. She continued to be a political activist until her death in 2013. Read more about Jessie’s life in the book Jessie De La Cruz: A Profile of a United Farm Worker by Gary Soto.

|

|

Dorothy DayDorothy Day worked as a journalist with the Socialist Call and The Liberator, and served as editor of The Masses until it was closed during the Red Scare. She was arrested and jailed after protesting at the White House for women’s right to vote, and she went on hunger strike while incarcerated. In 1933, Day co-founded the radical Catholic Worker movement and newspaper. Day was a leader in the Catholic Worker movement for several decades, influencing Catholic attitudes towards organized labor, war, and, sometimes, religion. Learn more about Dorothy Day at the Catholic Worker. |

|

|

|

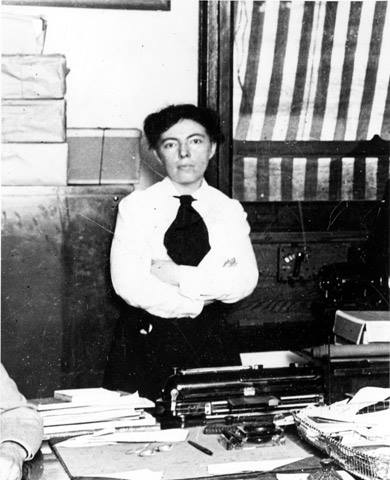

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn“I will devote my life to the wage earner. My sole aim in life is to do all in my power to right the wrongs and lighten the burdens of the laboring class.” In 1907, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn became a full-time organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and in 1912 traveled to Lawrence, Massachusetts during the Great Textile Strike. With the arrests of Joseph Ettor and Arturo Giovannitti Flynn at the end of January she became “the strike’s leading lady.” She was a major organizer of the various trips by children of textile workers to supportive cities like New York. She called the children’s demonstrations “the most wonderful that I have ever seen. I have been in strikes and battles for free speech but I have never seen such an outburst of human brotherhood as I saw Saturday.” Read more about Elizabeth Gurley Flynn at the Bread and Roses Centennial website.

|

|

|

Vicki GarvinVictoria (Vicki) Garvin was an African-American trade union and political activist as well as a pan-Africanist and internationalist. From 1946-1950, Garvin served as a research director of the United Office and Professional Workers of America. In 1951, she took part in the formation of the National Negro Labor Council and became a national vice president and executive secretary of the New York City chapter. She taught English in Ghana between 1963-1964, and from 1964-1970, she taught English to advanced Chinese students at the Shanghai Foreign Languages Institute. [Description from the New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts.] Learn more about Garvin at the Freedom Archives. |

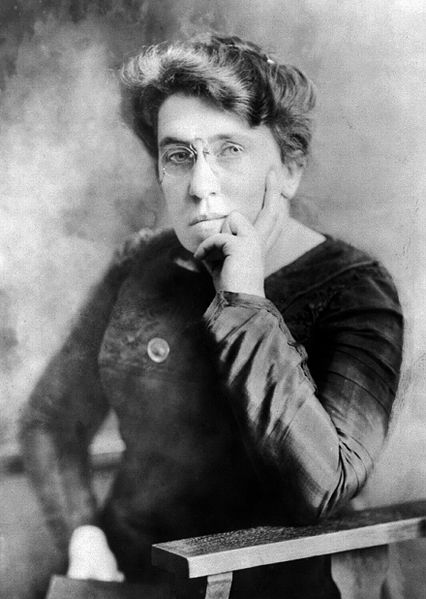

Emma Goldman“Still more fatal is the crime of turning the producer into a mere particle of a machine, with less will and decision than his master of steel and iron. Man is being robbed not merely of the products of his labor, but of the power of free initiative, of originality, and the interest in, or desire for, the things he is making.” In 1886, a year after her arrival from Lithuania, Emma Goldman was shocked by the trial, conviction, and execution of labor activists falsely accused of a bombing in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, which she later described as “the events that had inspired my spiritual birth and growth.” A born propagandist and organizer, Goldman championed women’s equality, free love, workers’ rights, free universal education regardless of race or gender, and anarchism. For more than thirty years, she defined the limits of dissent and free speech in Progressive Era America. Goldman died on May 14, 1940, and is buried in Forest Park, Illinois. [Description adapted from PBS American Experience.] Read more about Emma Goldman at University of California’s Emma Goldman Papers website.

|

|

Velma Hopkins, center, became active in the Civil Rights Movement. Here she is escorting the first Black student to the newly desegregated R. J. Reynolds High School in North Carolina. Image: Digital Forsyth. |

Velma Hopkins“I know my limitations and I surround myself with people who I can designate to be sure it’s carried out. If you can’t do that, you’re not an organizer.” Velma Hopkins helped mobilize 10,000 workers into the streets of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, as part of an attempt to bring unions to R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. The union, called Local 22 of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural, and Allied Workers of America-CIO, was integrated and led primarily by African American women. They pushed the boundaries of economic, racial and gender equality. In the 1940s, they organized a labor campaign and a strike for better working conditions, pay, and civil rights. It was the only time in the history of Reynolds Tobacco that it had a union. Before Local 22 faced set-backs from red-baiting and the power of Reynolds’ anti-unionism, it gained national attention for its vision of an equal society. This vision garnered the scrutiny of powerful enemies such as Richard Nixon and captured the attention of allies such as actor Paul Robeson and songwriter Woody Guthrie. Although Local 22 ultimately failed to slay the giant, the union influenced a generation of civil rights activists. [Description adapted from Jonathan Michels article, “Marker to honor 1940s labor union in city,” Winston-Salem Journal. Quote excerpted from the book Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth-Century South by Robert Rodgers Korstad.]

|

Dolores HuertaBefore becoming a labor organizer, Dolores Huerta was a grammar school teacher, but soon quit after becoming distraught at the sight of children coming to school hungry or without proper clothing. “I couldn’t stand seeing kids come to class hungry and needing shoes. I thought I could do more by organizing farm workers than by trying to teach their hungry children.” In 1955, Huerta launched her career in labor organizing by helping Fred Ross train organizers in Stockton, California, and five years later, founded the Agricultural Workers Association (AWA) before organizing the United Farm Workers (UFW) with Cesar Chavez in 1962. Some of her early victories included lobbying for voting rights for Mexican Americans as well as for the right of every American to take the written driver’s test in a native language. A champion of labor rights, women’s rights, racial equality, and other civil rights causes, Huerta remains an unrelenting figure in the farm workers’ movement. Biography adapted from City University of New York’s “Women’s Leadership in American History” (website unavailable) and the National Women’s History Museum.

|

|

Sonia IvanySonia Ivany was one of the first female members of the militant Puerto Rican organization the Young Lords. As a young Cuban mother and university student, she volunteered for the New York chapter’s early “garbage offensive.” In 1972, Ivany was a rank-and-file leader in an organizing campaign that unionized the largest voluntary hospital in the country, Columbia Presbyterian, into 1199. Ivany has been involved in the labor movement ever since, from being an organizer with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union to regional coordinator for the NYS Workforce Development Institute, AFL-CIO, and president of the NYC Labor Council for Latin American Advancement. She has also served on the national executive board of the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement. Watch Ivany tell her story in this video. |

|

Mother Jones“I asked the newspaper men why they didn’t publish the facts about child labor in Pennsylvania. They said they couldn’t because the mill owners had stock in the papers.” “Well, I’ve got stock in these little children,” said I, “and I’ll arrange a little publicity.” On July 7, 1903, Mary Harris “Mother” Jones began the “March of the Mill Children” from Philadelphia to President Theodore Roosevelt’s Long Island summer home in Oyster Bay, New York, to publicize the harsh conditions of child labor and to demand a 55-hour work week. During this march she delivered her famed “The Wail of the Children” speech. Roosevelt refused to see them. Read about the march here (thanks to Bread and Roses 1912-2012 for the link) at the Global Nonviolent Action database. Learn more about Mother Jones at the Zinn Education Project website.

|

|

Mary Lease“Wall Street owns the country. It is no longer a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street, and for Wall Street.” These words were spoken more than 120 years ago by Mary Lease, a powerful voice of the agrarian crusade and the best-known orator of the era, first gaining national attention battling Wall Street during the 1890 Populist campaign. As a spokesperson for the “people’s party,” she hoped that by appealing directly to the heart and soul of the nation’s farmers, she could motivate them to political action to protect their own interests not only in Kansas but throughout the U.S. “You may call me an anarchist, a socialist, or a communist, I care not, but I hold to the theory that if one man has not enough to eat three times a day and another man has $25,000,000, that last man has something that belongs to the first.” Mary spent most of her life speaking out in favor of social justice causes including woman suffrage and temperance, and her work reflected the multifaceted nature of late nineteenth-century politics in the U.S. [Description adapted from the Kansas Historical Society.]

|

|

Clara Lemlich“I have listened to all the speakers, and I have no further patience for talk. I am a working girl, one of those striking against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in generalities. What we are here for is to decide whether or not to strike. I make a motion that we go out in a general strike.” Clara Lemlich was a firebrand who led several strikes of shirtwaist makers and challenged the mostly male leadership of the union to organize women garment workers. With support from the National Women’s Trade Union League (NWTUL), in 1909 she led the New York shirtwaist strike, also known as the Uprising of the 20,000. It was the largest strike of women at that point in U.S. history. The strike was followed a year later by the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire that exposed the continued plight of immigrant women working in dangerous and difficult conditions. Read more at PBS American Experience.

|

|

|

|

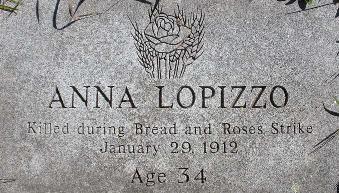

Anna LoPizzoAnna LoPizzo was a striker killed on Jan. 29, 1912 during the 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike, considered one of the most significant struggles in U.S. labor history. Three strike leaders — Joe Ettor, Joe Caruso and Arturo Giovannitti — were charged as accessories before the fact in LoPizzo’s death. Students could learn a lot from reading about their extraordinary case. Image and description from the Bread and Roses 1912-2012 Centennial Exhibit page.

|

|

|

Luisa MorenoLuisa Moreno, a Guatemalan immigrant, had her first experience with labor activism in 1930 at Zelgreen’s Cafeteria in New York City with her co-worker to protest exploiting its workers with long hours, constant sexual harassment, and the threat, should anyone object, of dismissal. Hearing that workers would picket the cafeteria, police formed a line on the sidewalk that allowed customers to pass through. Luisa, in a fur collar coat, strolled through the cordon of policemen as if she was going to enter the cafeteria. When she was directly in front of the door she pulled a picket sign from under her coat and thrust it in plain view, yelling, “Strike!” Two burly policemen grabbed her by the elbows. They lifted her off the sidewalk and hustled her into the entranceway of a nearby building. She came out with her face bleeding and considered herself fortunate that she was not disfigured. Moreno spent the next 20 years organizing workers across the country before taking a “voluntary departure under warrant of deportation” on the grounds that she had once been a member of the Communist Party. [Description adapted from San Diego Reader and SanDiegoHistory.org.] Read more about Louisa Morena at SanDiegoHistory.org. |

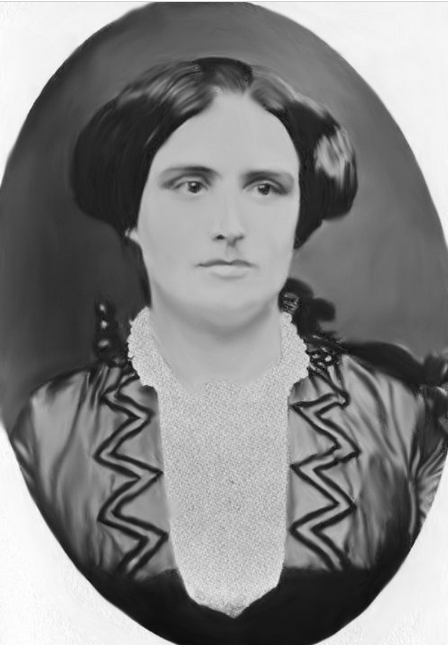

Kate MullaneyIrish American laundry worker Kate Mullaney became a union organizer and labor activist out of necessity in February 1864, when she was inspired by a men’s union to take her fellow laborers on strike. From The New York State Public Employees Federation pamphlet, “Kate Mullany: A True Labor Pioneer:” Shortly after forming the union, at noon on Wednesday, February 23, 1864, approximately 300 women went on strike from the 14 commercial laundry establishments. That afternoon Kate met with the women to discuss their demands for a 20 to 25 percent wage increase and their concerns with the introduction of the starching machines, which were scalding hot to handle. . . on February 28th a few of the proprietors gave in to their workers’ demands and the following day other employers followed. Their first strike was successful and Mullaney continued to put pressure on the local laundry and starch-collar industry. She garnered national recognition when the National Labor Congress appointed her as an assistant secretary. In that position, she corresponded with and organized laboring women across the country. See the book Working Women of Collar City: Gender, Class, and Community in Troy, New York, 1864-1886 by Carole Tubin and visit the Kate Mullaney National Historic Site (an affiliated area with the National Park Service) for more information. |

|

Agnes Nestor“Any new method which the company sought to put into effect and disturb our work routine seemed to inflame the deep indignation already burning inside us. Thus, when a procedure was suggested for subdividing our work, so that each operator would do a smaller part of each glove, and thus perhaps increase the overall production — but also increase the monotony of the work, and perhaps also decrease our rate of pay — we began to think of fighting back.” This reminiscence by Nestor described how the oppressive conditions of the glove factory pushed her to take a leading role in a successful strike of female glove workers in 1898. Soon she became president of her glove workers local and later a leader of the International Glove Workers Union. She also took a leading role in the Women’s Trade Union League, serving as president of the Chicago branch from 1913 to 1948. Read more of Agnes Nestor’s story at History Matters at George Mason University.

|

|

Pauline Newman“All we knew was the bitter fact that after working 70 or 80 hours in a seven-day week, we did not earn enough to keep body and soul together.” Pauline Newman, a Russian immigrant, began working at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1903 when she was thirteen years old. Finding that many of her co-workers could not read, she organized an evening study group where they also discussed labor issues and politics. Newman was active in the shirtwaist strike and the Women’s Trade Union League. She became a union organizer for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and director of the ILGWU Health Center. Courtesy of the Kheel Center. View photos of the fire at the Remembering 1911 Triangle Factory Fire website. Read more about Pauline Newman at PBS American Experience.

|

|

Lucy ParsonsOn May 1, 1886, Lucy Parsons helped launch the world’s first May Day and the demand for the eight-hour work day. Along with her husband, anarchist and activist Albert Parsons, and their two children, they led 80,000 working people down Chicago streets and more than 100,000 also marched in other U.S. cities. A new international holiday was born. Parsons went on to help found the International Workers of the World (IWW), continued to give speeches, and worked tirelessly for equality throughout the rest of her life until her death in 1942. Read more about Lucy Parsons in this profile by William Katz at the Zinn Education Project website.

|

|

Frances PerkinsOn March 4, 1933, Frances Perkins became the U.S. Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945, and the first woman appointed to the U.S. Cabinet. Having personally witnessed workers jump to their death during the Triangle Shirtwaist fire, Perkins promoted and helped passed strong labor laws. Read more at the Frances Perkins Center website.

|

|

Rose PesottaRose Pesotta arrived in Los Angeles in 1933 to organize employees in the garment industry with a workforce of 75 percent Latinas. The local leadership of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), mostly white men, had no interest in organizing female dressmakers, feeling that most either leave the industry to raise their families or shouldn’t be working in the first place. On October 12, 1933, a month after Pesotta arrived, 4,000 workers walked off the job and went on strike. Their demands included union recognition, 35-hour work weeks, being paid the minimum wage, no take home work or time card regulation, and disputes to be handled through arbitration. The strike ended on Nov. 6 with mixed results. The workers gained a 35-hour workweek and received the minimum wage. While the end seemed less than eventful, the message sent was far more powerful than the end result. What Rose Pesotta knew all along was now clear to the garment bosses and her male union counterparts; women, specifically women of color, should not be discounted. When it comes to the demands of dignity and respect, these workers would not be ignored. Read more at the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, 324.

|

|

|

|

Ai-Jen PooWhen Ai-Jen Poo started organizing domestic workers in 2000, many thought she was taking on an impossible task. Domestic workers were too dispersed, spread out over too many homes. Even Poo had described the world of domestic work as the “Wild West.” Poo’s first big breakthrough with the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) happened on July 1, 2010, when the New York state legislature passed the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. The bill legitimated domestic workers and gave them the same lawful rights as any other employee, such as vacation time and overtime pay. Though the bill was considered a major victory, the NDWA did not stop there, expanding operations to include 17 cities and 11 states. Read more about the NDWA here: http://www.domesticworkers.org/ [Description from Americans Who Tell the Truth website.]

|

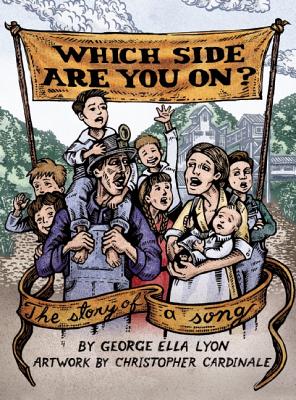

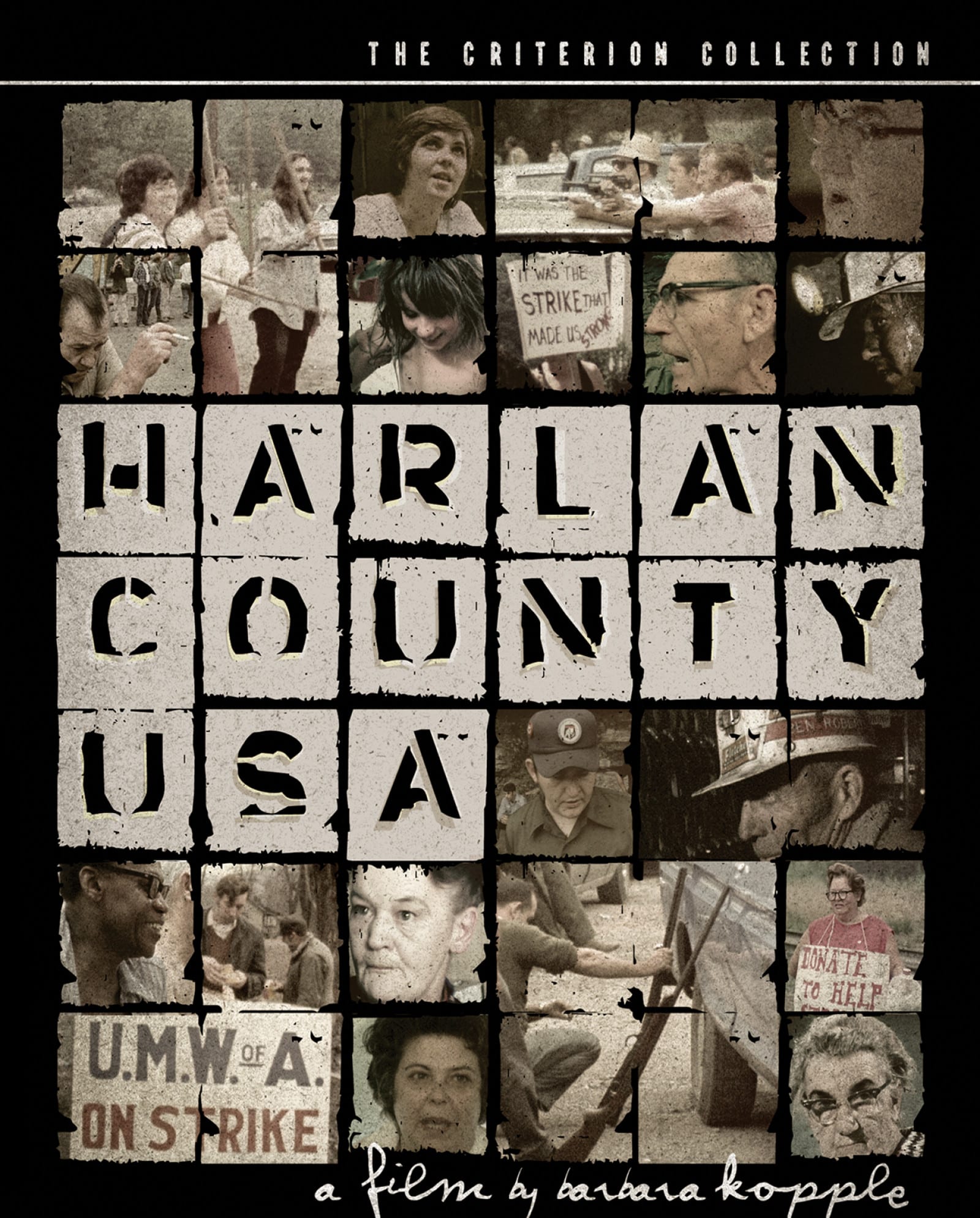

Florence ReeceFlorence Reece was an activist, poet, and songwriter. She was the wife of one of the strikers and union organizers, Sam Reece, in the Harlan County miners strike in Kentucky. In an attempt to intimidate her family, the sheriff and company guards shot at their house while she and her children were inside (Sam had been warned they were coming and escaped). During the attack, she wrote the lyrics to Which Side Are You On?, a song that would become a popular ballad of the labor movement. Song Lyrics CHORUS: Which side are you on? (4x) My daddy was a miner/And I’m a miner’s son/And I’ll stick with the union/‘Til every battle’s won [Chorus] They say in Harlan County/There are no neutrals there/You’ll either be a union man/Or a thug for JH Blair [Chorus] Oh workers can you stand it?/Oh tell me how you can/Will you be a lousy scab/Or will you be a man? [Chorus] Don’t scab for the bosses/Don’t listen to their lies/Us poor folks haven’t got a chance/Unless we organize [Chorus]

|

|

|

|

Harriet Hanson RobinsonAt the age of 10, Harriet Hanson Robinson got a job in textile Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts to help support her family. When mill owners dropped wages and sped up the pace of work, Harriet and others participated in the 1836 Lowell Mill Strike. Later as an adult, Harriet became an activist for women’s suffrage and would recount her mill work experience in Loom and Spindle or Life Among the Early Mill Girls. Harriet concludes: Such is the brief story of the life of every-day working-girls; such as it was then, so it might be to-day. Undoubtedly there might have been another side to this picture, but I give the side I knew best — the bright side! Download a PDF of Loom and Spindle or Life Among the Early Mill Girls from the University of Massachusetts—Lowell.

|

Fannie SellinsFannie Sellins was known as an exceptional organizer that also made her “a thorn in the side of the Allegheny Valley coal operators.” The operators openly threatened to “get her.” After being an organizer in St. Louis for the United Garment Workers local and in the West Virginia coal fields, in 1916 Sellins moved to Pennsylvania, where her work with the miners’ wives proved to be an effective way to organize workers across ethnic barriers. She also recruited black workers, who originally came north as strikebreakers, into the United Mine Workers America. During a tense confrontation between townspeople and armed company guards outside the Allegheny Coal and Coke company mine in Brackenridge on August 26, 1919, Fannie Sellins and miner Joseph Strzelecki were brutally gunned down. A coroner’s jury and a trial in 1923 ended in the acquittal of two men accused of her murder. [Adapted from ExplorePAHistory.com and University of Pittsburgh’s Labor Legacy website.]Read more about Fannie Sellins at the Illinois Labor History Society. and introduce her story to young people with Fannie Never Flinched: One Woman’s Courage in the Struggle for American Labor Union Rights.

|

|

Kate Hyndman, Stella Nowicki, and Sylvia Woods from the documentary, “Union Maids.” |

Vicky Starr“When I look back now, I really think we had a lot of guts. But I didn’t even stop to think about it at the time. It was just something that had to be done. We had a goal. That’s what we felt had to be done, and we did it.” “Stella Nowicki” was the assumed name of Vicki Starr, an activist who participated in the campaign to organize unions in the meatpacking factories of Chicago in the 1930s and ‘40s. Here’s a video clip of actress Christina Kirk reading Vicky Starr’s account of the conditions of working in the plants and tactics used to organize workers.

|

|

|

Emma Tenayuca“I was arrested a number of times. I never thought in terms of fear. I thought in terms of justice.” Emma Tenayuca was born in San Antonio, Texas on Dec. 21, 1916. Through her work as an educator, speaker, and labor organizer, she became known as “La Pasionaria de Texas.” From 1934–48, she supported almost every strike in the city, writing leaflets, visiting homes of strikers, and joining them on picket lines. She joined the Communist Party and the Workers Alliance (WA) in 1936. Tenayuca and WA demanded that Mexican workers could strike without fear of deportation or a minimum wage law. In 1938 she was unanimously elected strike leader of 12,000 pecan shellers. Due to anti-Mexican, anti-Communist, and anti-union hysteria Tenayuca fled San Antonio for her safety but later returned as a teacher. Learn more about her life and view and primary documents in the children’s book, That’s Not Fair! Emma Tenayuca’s Struggle for Justice/¡No Es Justo!: La lucha de Emma Tenayuca por la justicia on the Zinn Education Project website.

|

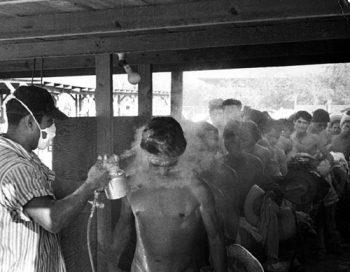

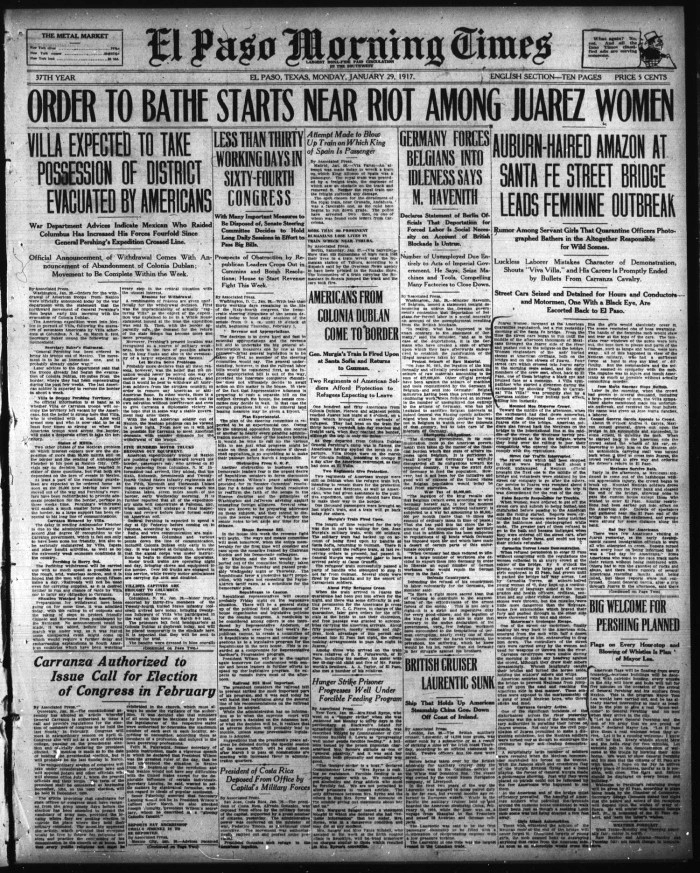

Carmelita TorresOn Jan. 28, 1917, 17-year-old Carmelita Torres led the Bath Riots at the Juarez/El Paso border, refusing the toxic “bath” imposed on all workers crossing the border. Here is what the El Paso Times reported the next day: When refused permission to enter El Paso without complying with the regulations the women collected in an angry crowd at the center of the bridge. By 8 o’clock the throng, consisting in large part of servant girls employed in El Paso, had grown until it packed the bridge half way across. Led by Carmelita Torres, an auburn-haired young woman of 17, they kept up a continuous volley of language aimed at the immigration and health officers, civilians, sentries and any other visible American.  Mexican laborers being fumigated with the pesticide DDT in Hidalgo, Texas, in 1956. Learn more in this article by David Dorado Romo, author of Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juarez: 1893-1923. Read the newspaper article at the El Paso Times website.

|

|

Ella May Wiggins“She died carrying the torch for social justice.” Ella May Wiggins was an organizer, speaker, and balladeer, known for expressing her faith in the union, the only organized force she had encountered that promised her a better life. On Sept. 14, 1929, during the Loray Mill strike in Gastonia, North Carolina, a Textile Workers Union members were ambushed by local vigilantes and a sheriff’s deputy. The vigilantes and deputy forced Ella May Wiggins’ pickup truck off the road, and murdered the 29 year-old mother of nine. Though there were 50 witnesses during the assault and five of the attackers were arrested, all were acquitted of her murder. After her death, the AFL-CIO expanded Wiggins’ grave marker in 1979, to include the phrase, “She died carrying the torch of social justice.” Her best-known song, A Mill Mother’s Lament, was recorded by Pete Seeger, among others. Read more at NCpedia.org.

|

|

Sue Cowan WilliamsSue Cowan Williams represented African-American teachers in the Little Rock School District as the plaintiff in the case challenging the rate of salaries allotted to teachers in the district based solely on skin color. The suit, Morris v. Williams, was filed on Feb. 28, 1942, and followed a March 1941 petition filed with the Little Rock School Board requesting equalization of salaries between Black and white teachers. While she initially lost the case, she won in a 1943 appeal. Read more at the Encyclopedia of Arkansas website.

|

You forgot Eleanor Roosevelt. Sadly most think of her as only a First Lady, but she was far from lady-like!

There is a wonderful example of a worker named Luisa Capetillo in the Early XX century she single-handedly organized the whole northeastern part of Puerto Rico. She confronted the strikebreakers face to face and acted in dramas promoting equal opportunities for the working class. She was the first woman to dress like a man. She did it to get attention for her policies! At a time when women couldn’t read or write, she published four books on modernist thought and worker’s rights. She died young at the age if 42 but left a legacy no one would forget!.

Good choices. Very important and interesting. But I miss Mary Anderson, labor leader in WTUL and Boots and Shoe Worker´s Union and later on the boss om Women´s Bureau in US Labor Department 1920-1964.

I think Helen Keller, Frances Perkins and Dolores Huerta should definitely be on this list!

Look into what’s happened with Jefferson County School District near Denver, CO. Outside money was poured into the school board election and three extremely conservative anti-union board members were voted in. They have now hijacked a great district, refute third party fact finders’ and arbitrators’ reports, and won’t renew teacher contracts. These people have never taught children, yet espouse that they know what’s best. Jeffco is one of the largest districts in the US, and Americans need to pay attention to what is happening there.