On June 12, 2023, Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw joined Cierra Kaler-Jones, Rethinking Schools executive director, and Jesse Hagopian, Rethinking Schools editor and high school teacher, to talk about critical race theory and the attacks on teaching about U.S. history. This Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class was one of our 2023 Teach Truth Day of Action activities.

On June 12, 2023, Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw joined Cierra Kaler-Jones, Rethinking Schools executive director, and Jesse Hagopian, Rethinking Schools editor and high school teacher, to talk about critical race theory and the attacks on teaching about U.S. history. This Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class was one of our 2023 Teach Truth Day of Action activities.

Crenshaw sounded the alarm about the times we are in,

We have the Lost Cause on steroids, because we’re talking about a very few, a minority of a minority, being able to dictate the terms by which we can know our own lives and the terms by which we can create our own futures.

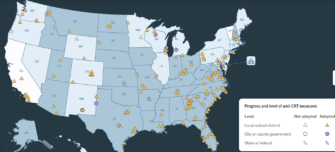

It’s important to look at those maps and see that the same states that are behind the effort to suppress the right to vote are the same states that are behind anti-woke laws. They’re the same states that are banning the books. They’re the same people who are banning the right to choose.

Participants shared what they learned and the impact of the session:

This class re-lit my fire and my determination to keep going!!

A reminder that knowledge is power. Something I obviously know, but the connection to obstructing avenues to knowledge actually being an obstruction to accessing and exercising your power was enforced tonight.

As much as the incisive ideas, being in community with people across the country doing such radical and important work was incredibly edifying.

This history is continual. I loved when Dr. Crenshaw stated, “You can’t be surprised at the January 6th [attempted insurrection] if you know about the period of Redemption.” It is so imperative that we teach Reconstruction and we demonstrate that there has been a concerted effort in this country to miseducate our citizenry when it comes to justice issues.

In addition to the conversation with Crenshaw, participants heard from teachers Lindsay Paiva and T. J. Whitaker — Teaching for Black Lives study group leaders from Rhode Island and New Jersey, respectively. They described the #TeachTruth Day of Action events that they helped to coordinate on Saturday, June 10.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: Well, I’m really happy to get to welcome Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw, the co-founder and executive director of the African American Policy Forum and a bicoastal professor of law at both UCLA and Columbia. She’s a brilliant scholar and writer on civil rights, Critical Race Theory, Black feminist legal theory, race, racism and the law. I also just want to say that her work has meant a lot to me as a teacher in my own classroom. For years, I’ve begun every school year with using her writing and an online speech that she gave from the Women of the World [WOW] Conference in 2016 to introduce my students to the concept of intersectionality, and then using that concept throughout the year, tracing intersectional identities in every unit that we’re studying. It’s just been so foundational to my students’ understanding of the world. So thank you for that, and welcome, Dr. Crenshaw.

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Thank you, Jesse. From here on in, it’s Kim and Jesse.

Jesse Hagopian: Right on, I appreciate you. I have an opening question for you about the moment that we’re in. So, let’s just jump right into it. When the Republican Party began labeling everything that scares them as Critical Race Theory, and then attacking it, I think too few people had any idea what CRT was, including the conservatives launching the attack and most of the teachers who are being targeted as teaching Critical Race Theory. So, while antiracist teachers certainly share a commitment with critical race theorists to teach a structural analysis of racism, I think very few have ever really been formally educated themselves about CRT. As one of the founding practitioners in the field, I was hoping you could talk to us about what Critical Race Theory is and how learning CRT could improve teaching and learning in the classroom.

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Thank you, Jesse. And thank you for starting with the observation that the attack on Critical Race Theory has nothing to do with what Critical Race Theory actually is. Also, I think acknowledging one of the challenges that those of us who were and are attacked by Critical Race Theory face, which, an attack was made. People didn’t know what the attack was about, neither side knew. That didn’t stop the conservatives from making the attack, but it did stop those who were being attacked from knowing what to say and how to defend the work that is vital and that’s necessary.

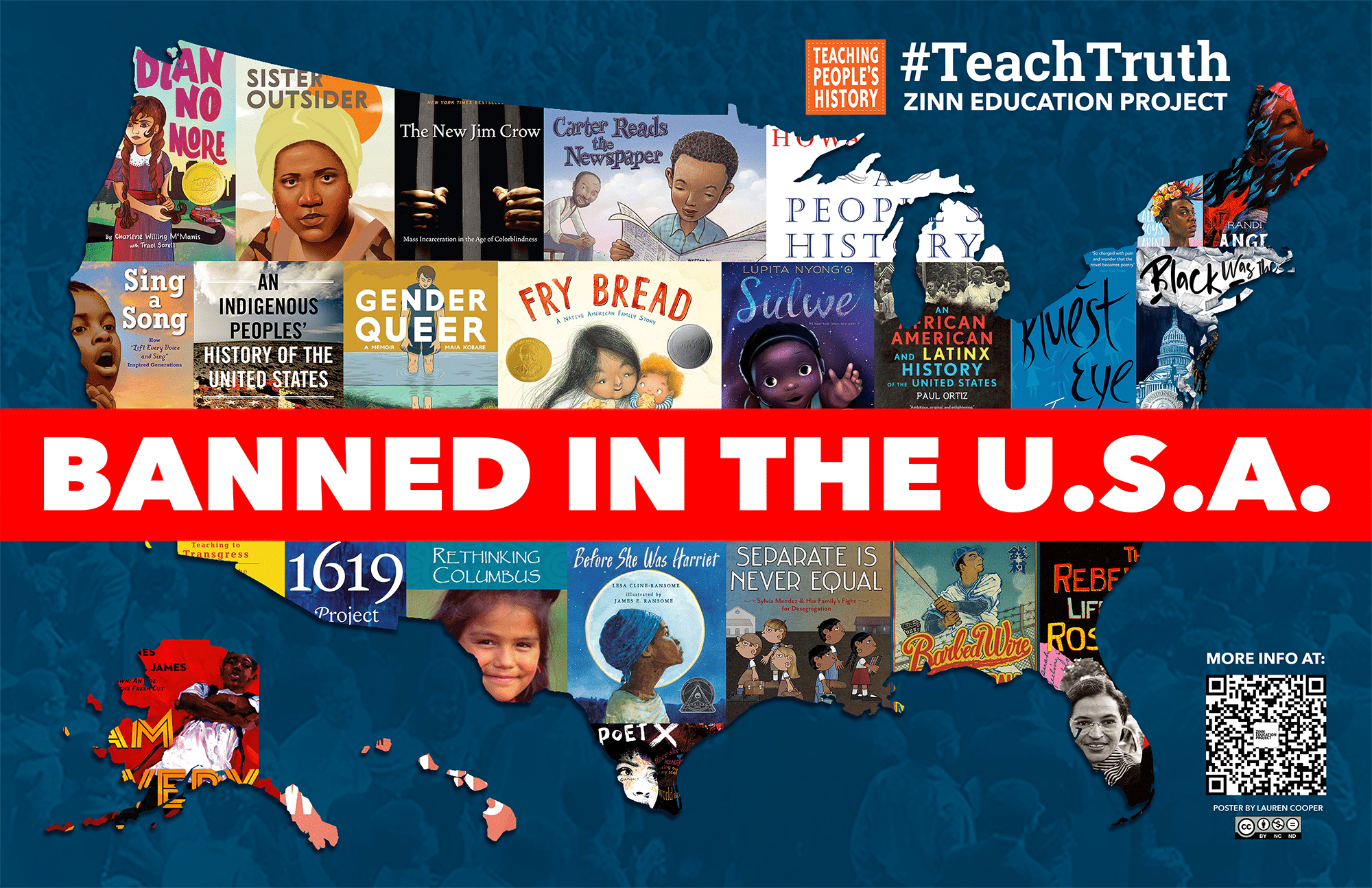

And Jesse, I think you remember when we first started working together, one of the real challenges that we were facing with so many teachers and defenders saying, “Well, Critical Race Theory isn’t even taught in K through 12,” which, you know, we called it the pivot. Even the first couple of months, I was saying, “Well, look, I’m not seeing . . . our book isn’t flying off the shelves. So I don’t know what’s going on.” It took us all a while to realize that Critical Race Theory was being used as a generic term for anything that was antiracist, any antiracist education, any education that elevated structural racism, any education that dealt with the policies and the practices that were grounded in the past that continue to produce racially inequitable outcomes and institutions. All of that was packaged into the category, the Trojan horse, called Critical Race Theory. So, while we were saying, “Oh, it’s not even being taught in K through 12,” in fact, they were going after what was being taught in K through 12. They were going after Ruby Bridges. They were going after the Montgomery Bus Boycott. They were going after Tulsa. They were going after the Federal Housing Act in the way that it created racially segregated housing stock that now is more consequential today than it was even when it happened. Because, as we know, the huge wealth disparity between African Americans and white Americans can trace its way back to the 1940s, when the white middle class was created out of federal housing policy.

So, it’s taken us two years for all of us to realize that there’s a shell game going on here. What they are calling Critical Race Theory is everything that is about our racial history and our contemporary racial reality. So we have shifted the way that we respond to it: rather than saying, “We don’t teach Critical Race Theory,” we take seriously what they say thereafter, and then we talk about, “Well, what does it mean to give your child a talk, if you’re African American, what does it mean to acknowledge that when you see the sirens in the rearview mirror, you put your hands at the ten and two o’clock position? What does it mean to tell our children that we have to be twice as good to go half as far?” These are all moments of acknowledging that we do not live in a colorblind world, these are moments of acknowledging that race continues to shape the life chances of people differentially on the basis of race. That is structural racism. That is also implicit bias. That is also history creating the platform through which competition today is racialized. That is all part of Critical Race Theory.

So, we do exercises in many of our classes or talks in which we give people a whole range of scenarios and give them an A or B option. The A option is usually the colorblind, race denial option; the B is race realism. And most people opt for the B option. We say, “Congratulations, you are critical race theorists. If you understand these scenarios you are critical race theorists.” So that’s the broad way we’ve been talking about it.

There is a legal part of it that is historically what was Critical Race Theory. It’s basically the way that law reinforces structural forms of racism. Law tells us that these are race neutral and defensible. Law establishes, reinforces and protects racial privilege. That’s how Critical Race Theory was traditionally analyzed and talked about. It’s just the last disciplinary contribution to our overarching understanding about how race is constructed, how racism is rationalized, and how it can be reinforced unless we have the tools to identify it, dismantle it, and create structures that are opportunity positive.

Jesse Hagopian: Thank you so much for that.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Yeah, thank you for breaking that down for us, just the language that CRT gives us to be able to do this type of analysis. You mentioned the historical context of CRT and the legal aspect of it, so, as a follow up, I’d actually love for us to look at some of the language in Iowa’s divisive concepts bill. This is something, as educators, we can do in our classrooms with students and see and analyze what the bill text actually says and have those critical conversations. Also, recognizing that in many places it is illegal and many educators are under fire and having legal repercussions to teaching this truth. But, I’d really love for us to go through this together. I’ll just read the bill text quickly, some examples.

So, “divisive concepts” includes all of the following. “One, that one race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex. Two, that the United States of America and the state of Iowa are fundamentally or systemically racist or sexist. Three, that an individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist or oppressive, rather, consciously or unconsciously,” and then skipping forward to “eight, that any individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of that individual’s race or sex.” And then “number nine, that meritocracy, or traits such as hard work ethic are racist or sexist, or were created by a particular race to oppress another race.” So, when we apply Critical Race Theory to this law, what insights does CRT give us?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Well, let’s start with the fact that this effort to effectively preclude certain topics and viewpoints is itself an embodiment of one of the main observations of Critical Race Theory, which is race, racism, racial power, racial privilege, racial domination, racial subordination facilitated by and through the law. It’s almost ironic, to say the least, that the anti-woke forces are actually using law to say that a discipline in law that looks at the way that racial power is encoded in law should be illegal. Proving the point. So, I mean, that’s like eyebrows off your head, like, really, this is the move that you’re going to make to disprove Critical Race Theory? Then when we start looking inside of it, Critical Race Theory is implicated in number one, the idea.

Let’s see, number eight, “that any individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress.” Now, this is an effort to create a right against the outcomes of education, it is an effort to say that certain people’s feelings will be protected against critical inquiry. Now, one move that one might make is to suggest that never has there been a time that the feelings of racialized, marginalized people has ever been the baseline for determining what is legitimate to teach and what is not. If anything, the entire field out of which many of us come — I come out of Africana Studies, other people come out of various ethnic studies traditions — remember when it first got started, but even today, they called that “me search.” They undermine the legitimacy of actually studying the histories in the political economy of socially marginalized groups. But, suddenly, when psychological distress becomes a concern, it is the psychological distress of those who are racialized as white rather than those who are marginalized.

So, Critical Race Theory looks at the distributional consequences of particular rules. It asks, who is benefited and who is harmed? It goes beneath the surface neutrality of the law to ask, what are its consequences and what are the levers that produced this particular effort to use the state to control ideas? There’s no better example of Critical Race Theory being used to see how law is embodying racial interests and disadvantaging particular racial interests.

The last thing that I’ll say is Critical Race Theory elevates history. It looks at patterns and repetitious dimensions of how disempowerment happens. Divisive concepts, as we all know, was the idea that segregation is used against the Civil Rights Movement. Divisive was the idea that the sit-ins and the Freedom Riders were basically the product of outside agitators. Well, let’s think about it in the context of racial power — to define these moments and these movements as divisive means that your understanding of unity turns on and is dependent on maintaining the racial power that preexisted. So, when the Civil Rights Movement was framed as divisive, what did that mean unity turned on? Unity turned on non-contested white supremacy. When these ideas are brought forward to this moment — when critical thinking about race, when so-called wokeism is framed as divisive — what it is telling us is that the baseline against which this is called divisive is actually acceptable, defensible, and requires insulation.

Well, what are all those things? A world without antiracism, a world without critical thinking about race, a world without race consciousness is a world in which life chances are racialized, a world in which lives are shorter, a world in which health is less robust, a world in which wealth is tremendously disproportionate, a world in which police can take lives without having to think twice about it. That is the world that’s being defended as the world that is non-divisive, that is uniform, that is universal. Well, we know when they say that what we’re doing is divisive, what we’re actually interrupting is the assumption that white supremacy and its contemporary manifestations is completely and totally defensible, and our efforts to interrupt it is what is being divisive. Critical Race Theory brings that analysis into those claims and gives us the tools that are necessary to disrupt the hold that that has on our demands for justice.

Jesse Hagopian: That’s so useful. I can see myself using that law from Iowa in the classroom and having the students analyze it and then showing this very segment to the students to have them think more deeply about the context of those laws. I always love how you thoroughly research the history that has led up to the moments that we’re talking about and use the history to understand what’s going on today.

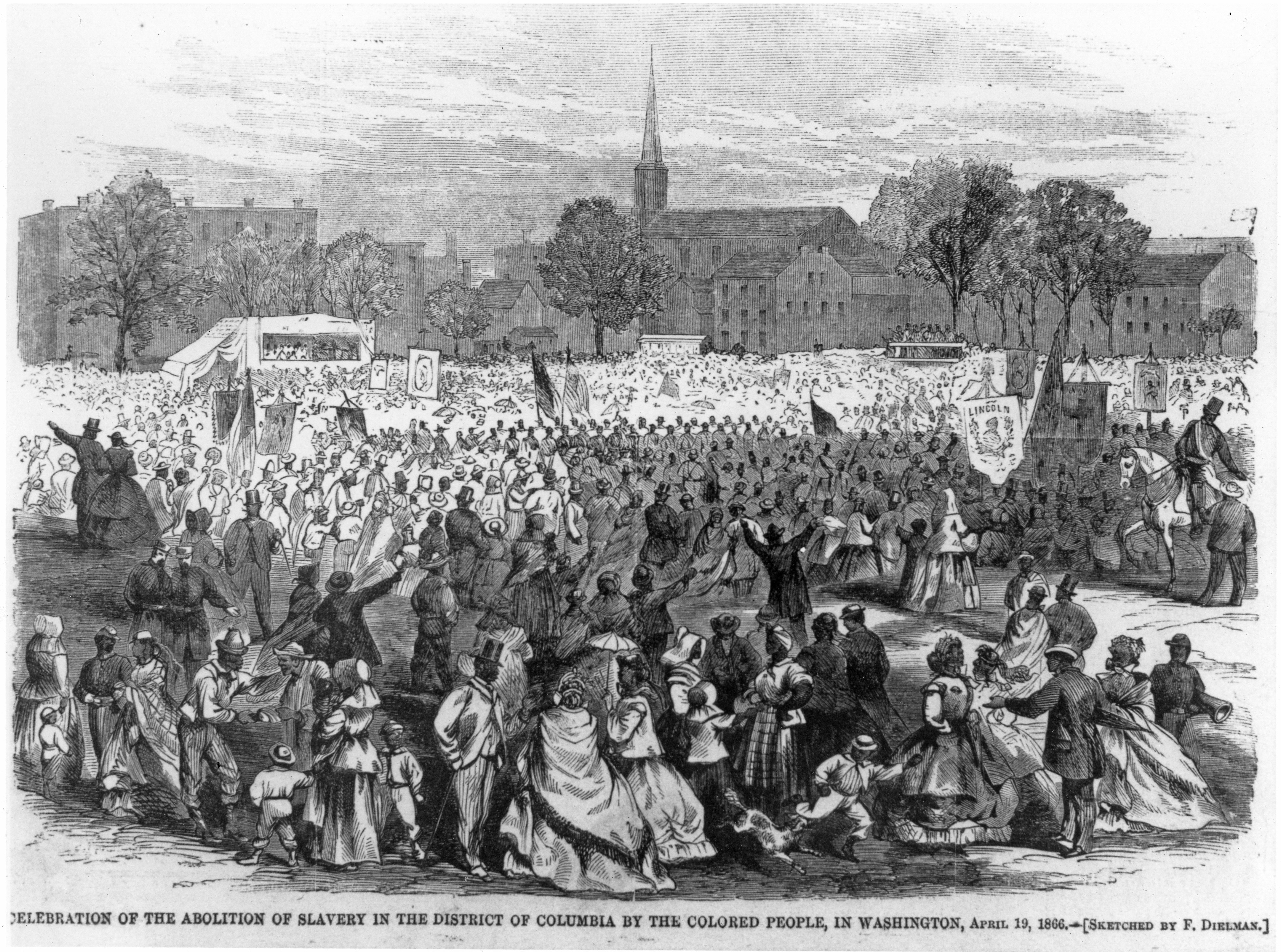

So, I wanted to go that direction now and ask you about the Stono Rebellion in 1739, where enslaved people were outlawed from learning to read and write the following year. As you know, hundreds of Black schools were burned down during Reconstruction, over 600. They burnt down Freedom Schools during the Civil Rights Movement. From the Jim Crow era until today, Black schools in the south and the north have been dramatically underfunded by billions of dollars, according to some recent studies. So, why has Black education always been such a threat to some people in this country and what role can the struggle for antiracist education play in broader movements for social justice and freedom?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Well, you know, this is exactly where Freedom to Learn lives, Jesse. So, just the basics, knowledge is power. We know that because those who are in power want to take the knowledge away from us. So, to sustain and maintain power — particularly to sustain and maintain the status of enslaved people, to sustain and maintain the status of economically marginalized people, to sustain and maintain the disenfranchisement of those people — the key to that is depriving them of the knowledge that they need in order to be literate about the ways in which their subordination is reinforced and made to appear to simply be the way things have to be. You know, our holiday that’s coming up next week, Juneteenth, it’s partly, truly about emancipation. But it’s really about knowledge, because without knowing the status of being freed, without the news arriving to the Texas freedmen that they were, in fact, no longer enslaved people, they were unable to claim their freedom. So, this is power showing us how significant, how important, how absolutely essential knowledge is to realize the freedom that is ours to take.

If we look, as you just noticed, over history at every point where it was necessary to push back against liberation struggles, at every point where the demands for liberty, the demands for freedom reached a crucial, critical point of inflection, the push back, the resistance, the retrenchment, went to knowledge, it went to what you can learn, what you can teach — whether you can read, what you could read, what you could write, what you could say. In this country, to even write about the demands for emancipation was considered sedition. It was against the state’s interests to actually be able to advocate for Black freedom.

We like to think that that was a century and a half ago, we like to thank God that that’s not the world we live in anymore. But think about it. Is it really that long ago? Are we really free from that when we can be in a society where 22 states have passed what they call “anti-woke laws”; where there are particular things that cannot be said in the classroom about racism and white supremacy; where if teachers do say these things, or come close to being interpreted to be saying these things, that they can lose their jobs, they could lose their licenses? We think that we’re not in that period anymore, where the state can dictate what knowledge is available. I think if we think seriously about the continuation of this suppression, over time, if we look all the way back to 1739 and ask, what were the motivating factors that cause both the state and vigilantes to attack education, and draw the clear line to Moms for Liberty, to American Legislative [Exchange] Council, to foundations to the Republican Party? If we ask what the connections are, the connections are liberty demands are met with the absolute imperative to shut down the ability to be literate, to learn, to understand, to read, to write, to advocate, and to say, this is the same struggle. As they say, “Old wine, new bottles, still does the same thing.”

Cierra Kaler Jones: Yes, yes, yes. I just appreciate how you continue to point us back to the patterns that show up through history, and how the opposition doesn’t want us to be able to uncover those patterns because we change them through our resistance. So, speaking of another pattern in history, we’ve seen some of these same tactics, as you’ve named, play out in history as a means of stifling movements for social justice. Periods of advancement towards social justice have always been met with white supremacist backlash, so given the right-wing narratives about protecting children, this idea that they’re against shaming white kids in schools by teachers pushing CRT, can you talk about the connection between how the redbaiting of the Red Scare was used to attack the Civil Rights Movement?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: It’s such an understudied period of our history. I think that there is the assumption that, again, that that period is behind us and that we have transcended it, rather than recognizing that, in fact, freedom struggles — particularly freedom struggles of the descendants of enslaved people — have never overcome the distorting effect of the Red Scare. Our very ways of conceptualizing racism and white supremacy, for example, the idea that racism is basically a thought crime and not a structural crime, that it can be corrected by goodwill rather than redistribution of stolen wealth, that the solution is not seeing race rather than dismantling whiteness and white privilege, these are all consequences of the tremendous pressure that was placed on Black freedom seekers in the 40s and the 50s to shrink the territory, shrink the terrain upon which racism was being contested. To fold it into comfortable narratives about American exceptionalism, to fold the problem into a package that could be solved by expressions of goodwill and goodness as opposed to understanding the problem in terms of its implications across the economy, across the political structure and across many institutions that embodied and reproduced white privilege and power.

How do we understand, then, why 50 years after the Civil Rights Movement, we still don’t have anything close to parity when it comes to matriculation in higher education; nothing close to parity when it comes to wealth; nothing close to parity when it comes to political power? How do we understand it? We understand it because all of those arenas were framed as sacrosanct and reinforced by the idea that if you even deemed to think it is important and valid to think about, well, you are actually showing that you are not dyed in the wool American, that you are red to the core, that you are anti-American, and that you represent expressly why Black freedom struggles had to be suppressed. You are sitting in the aftermath of COINTELPRO, of a federal government that basically sought to destroy the freedom movement using tools of anti-communism, using redbaiting, using the ability to separate out critical thinking from what was considered to be safe and comfortable. We’ve not overcome that; it’s still shaping how freedom demands are understood. And the kicker is that, at the end of the day, the use of innocence, the use of the white child as the subject that must be protected at all costs, is the way that Brown v. Board was dismantled. It is the way that it was rendered illegitimate, it is the way that the project that was Brown v. Board of Education is largely over, and it is the way that the aftermath of that project, the knowledge that got developed, is now also being framed and shaped as destructive to the interests of white children and destructive to the interests of the republic. This is the aftermath of the great taming of the freedom struggle.

Jesse Hagopian: Yeah, wow. Thanks for grounding us in that history. I just want to point out to people that the Zinn Education Project has an incredible lesson on how to teach about COINTELPRO, since you mentioned COINTELPRO. Ursula Wolfe-Rocca created a really great lesson plan that I think everyone should use, and I’m really excited that the teachers are getting more of that history. Do you want to move to breakout groups now, Cierra? Should I ask one more question or move to breakouts?

Cierra Kaler-Jones: I think we’re at the point where we are moving into breakout rooms.

Jesse Hagopian: We’ve been digging into history a little bit when we left off and I want to pick right back up there, because one of the most instructive eras for drawing lessons about how to build a Black Freedom Movement is Reconstruction. Yet the Zinn Education Project report that we released shows just how poorly this era is taught in school, if it’s taught at all. State standards and textbooks still often promote a Lost Cause narrative that hides Black people’s tremendous advancements for freedom during this era. I am curious about what lessons you draw from Reconstruction that can help us in the struggle for antiracist education today, and what will it take to build a broad based mass movement to defend the right to teach the truth about systemic racism?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Wow, well, I’ll start with the Reconstruction question. We’re actually trying to think about where does the mass movement come, because we know that’s what we’re going to need in order to take our history back. When I think about Reconstruction and Critical Race Theory, the two basically mutually construct one another. Critical Race Theory takes up the question of how a civil war, how the successful effort to turn four million enslaved people into citizens, was ultimately and utterly dismantled by an institution called the Supreme Court, and that dismantling is not simply historical. All of the major cases that robbed the Reconstruction era laws of their enforceability are still good law. The civil rights cases, which was the case in which the Supreme Court basically said that the formula that Congress had created to first of all give us citizenship, make us citizens of the national government, and then empower Congress to protect us against racial violence, against discrimination, against being pushed out of the political arena, the court basically said that that entire formula was unconstitutional. The added dimension to it was to say that for us to expect to be protected in our new citizenship was for us to be expecting preferential treatment. In other words, a group of people less than 20 years after the end of enslavement, with the indention on our risk of the chains, we’re being told that we were expecting too much, that we were being preferred in order to have our rights as new citizens be protected by the government, that we helped to win the war to free us.

If preferential treatment could be used to dismantle emancipation less than 20 years after the end of slavery, think about what the frame of preferential treatment or reverse discrimination can do through the rest of history. That is exactly what’s happening now when people say teaching our history is violating their children’s interests. They’re practicing the same logic of the civil rights cases, when owners of restaurants and facilities said that to serve you violates our civil rights. They are practicing redeemer constitutionalism, which destroyed Reconstruction. When they say sending my children to an integrated school violates their rights to go to a segregated school they are rehearsing Reconstruction’s repeal. This stuff that we know is circular, is cyclical, that it is over and over again, is made possible because of the takeover of the courts by a white supremacist jurisprudence. That’s what we’re seeing happening now in this court. That’s why we’re likely to lose affirmative action, and that’s why it makes no sense to think about what’s happening solely in terms of the racial identity of the people doing the work. Clarence Thomas is as much a danger to the future of the Constitution and the future of marginalized people as Justice Taney was in 1865, 1870, 1875. The question is, what it is and how they use the law to reinforce redemption, to reinforce the Lost Cause, to reinforce the second class citizenship of non-whites. That’s what Critical Race Theory tries to unpack, uncover, and show how we’re always, constantly revisiting the opportunity to finally get it right. That’s what we’re confronted with today.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Oh, wow. I am just speechless. Oh, my goodness, yes, my mind is just blown. Those critical connections of history and what you just said, it’s something to just sit with. That’s what we’re confronted with today. Powerful. As we continue to talk a little bit about the law, one of the concepts that Ron DeSantis and the Florida Board of Education objected to when they denied the AP African American studies course was intersectionality, a term you developed to help us understand overlapping forms of privilege and oppression that inform our identities. I do have to say, personally, that your work helped me to have language from my own experience. And I believe that when we have that language, when we’re able to name something, then we’re able to organize either for or against it. So thank you for that language to understand my own experience. Why are racists and transphobes so scared of intersectionality and why is this idea so critical to teach to young people?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Well, Cierra, I think you just said it. If you can’t name something, if you don’t have a way of creating a container for the myriad experiences that reflect the same pattern, you are unable to hold it, to transform it. I think there is a recognition that these concepts, these ideas, allow things to surface in a way that allows them to be quantified, and consequently identified for transformation. Intersectionality has been, as you point out, used by any number of people, any number of groups, by overlapping patterns of disempowerment. When you can identify it then you are in a better position to be able to interrogate it, a better position to be able to build connections with people who you might not see as having common interests. You’re better able to dislodge the hold of “This is the way things have to be” and actually say, “No, nothing has to be this way. We can actually transform the lives that we have been given. We can transform the lives and the world in which we live.”

I mean, it doesn’t take me to say it: If you actually look at the people who have attacked intersectionality they will say precisely why they’re uncomfortable with the idea. They talk about the consequences of challenging the hegemony of certain people, particularly straight white cisgendered men, and they have been interestingly the ones that say intersectionality takes something away from them, it creates a new pariah. It only creates a pariah if you think that you’re right to being the subject of every story, the center of every project, the interest that always has to be reaffirmed. Only if you think that are you afraid of intersectionality. If, on the other hand, you are aware of, believe in, support the idea that democracy really requires us to find tools to tell the deeper story of who we are, finding resources to create truly inclusive educational practices — if you are of the mind that we all suffer when antiracism and democracy are both contested concepts — if that’s your belief, then intersectionality is not a threat at all.

I say this to just wrap it up. One of the points of departure for our work on advancing the Freedom to Learn is that the institutions and the thinking that we have to worry about the most when we’re trying to protect our freedom is not just the DeSantis’s of the world. They’re clearly problematic, but they are doing what their interests suggest they must do. They want to undermine our democracy, they want to marginalize, they want to keep the angry masses motivated and mobilized, so they are on mission and they are on point. The real problem is the educators claim to want to open up coursework that provides opportunity for the energies that came to fore during 2020, the young people who were demanding concepts to help them think about how they could have watched an African American man basically be killed over eight minutes, wanting to understand what is structural about racism. Those institutions that claim that they wanted to embrace this moment, but at the first moment that they ran into trouble against the DeSantis’s of the world, the first moment that the concepts like intersectionality, like structural racism, or the political movements like Black Lives Matter, were contested, they were willing to negotiate away, they were willing to throw these ideas under the bus. And in doing so saying, particularly with respect to intersectionality, these ideas have been so robbed of their meaning, they have been so diminished by controversy, that they’re no longer politically or educationally useful. That is enabling the right to do what they do.

All the right has to do is say ideas are controversial, or to say we don’t like these ideas, and when our centrist institutions like the College Board, like some of our publishers, when they’re willing to say, “Well, we have to back away from these ideas because they’re controversial,” they have given the victory to the DeSantis’s of the world. They are the ones who are willing to say, as long as there are some people who are willing to go to the mat, and we’re willing to take these ideas out of the curriculum, they are the ones that are making the right-wing successful. I’ll just remind everybody what happened to “The Hill We Climb.” One person complained about that and that person had the veto power over millions of people who were inspired by that poem. Now take that and multiply it, Critical Race Theory across antiracism across intersectionality, and we have not only the Lost Cause coming back again, we have the Lost Cause on steroids, because we’re talking about a very few, a minority of a minority, being able to dictate the terms by which we can know our own lives and the terms by which we can create our own futures.

Jesse Hagopian: Yes, absolutely. I’m so excited to dig more into this conversation about intersectionality. I’m even thinking, Cierra, that we should work on developing a lesson on intersectionality and the history of Black women — from Sojourner Truth to Claudia Jones to the Combahee River Collective to Kimberlé Crenshaw — tracing this history of detailing overlapping identities and systems of power and privilege and oppression so that students can can know that history and apply it to their lives today. So, that will be a project to come hopefully.

But, we just have a few more minutes here, the last four minutes maybe, so I want to jump into one more question because, Kimberlé, you’ve been so deeply involved in the movement to defend antiracist teaching, and I am so grateful not only for the immense intellectual contributions that you’ve given the Black Freedom Struggle and movements for social justice, but also your willingness to roll up your sleeves and get the work done and organize these days of action to help defend my colleagues and teachers all across the country doing this work. When way too many liberals were just sitting at home, hemming and hawing and wondering what to do when this attack on Critical Race Theory started, you all at the AAPF launched the Truth Be Told Initiative from the jump, and the Freedom to Learn Campaign and the CRT Summer School, and have participated in all these National Days of actions and this June 10 action. One of the messages you’ve been lifting up is the connection between the anti-CRT legislation and the tax on democracy. Can you just tell us a little bit more about that connection and what you think we need to be doing at this time strategically? What will it take to fight back against these forces?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Well, I want to thank you all for being our first partners in this work. As you remember very well, when President Trump signed the executive order basically laying the groundwork for what has now become a firestorm that has spread across the country, we say 22, 25, actually, 49 states have seen some kind of legislation introduced. It’s not just a red state problem. In fact, there are more of these local laws in California than even Texas. People are unaware that there are blue state arenas for precisely this struggle. So, our challenge consistently is not just primarily against the Maga nation — like I said, they’re going to do what they’re going to do — our challenges, our allies, are people who looked at January 6 and said, “That’s not who we are.” Which is basically telling us that they didn’t read anything about Redemption, they don’t really know the history, and if they do know the history, they are denying the extent to which that history constantly walks among us, always there to be reactivated again. There’s so many people who would say things like, “Well, it can’t happen here,” basically meaning Europe. It’s already happened here. What do they think Redemption was? What do they think genocide was? It is our own personal way in which fascist elements in American history attach themselves to white supremacy and find the easy path to the middle of the town square. That’s what it means to basically say anti-wokeness is going to be the primary theme, the primary organizing principle, through which Maga enforces and projects its values onto the public education system. We don’t have to ask or speculate; they had basically said, “We are going after public education. We are going after higher education. We want to dismantle this institution,” which was the primary driving institution behind the effort to dismantle white supremacy. It wasn’t an accident that Brown v. Board of Education took place in education. It wasn’t an accident that one of the most significant things that came out of Reconstruction was public schools. That is where we have laboratories of democracy, that is where we learn the idea that democracy is supposed to not be just about how we count votes but how we count belonging, how we count the conditions that have to be in place for us to actually say that any particular outcome is the product of mass participation.

What do you have to have to really participate in a democracy? You have to have education. It doesn’t exist without publicly funded, effective education. So that’s why it’s important to connect the dots, it’s important to look at those maps and see that the same states that are behind the effort to suppress the right to vote are the same states that are behind anti-woke laws. They’re the same states that are banning books; they’re the same people who are banning the right to choose; they are the same elements across all of these different states. So, it behooves us to find the connections because we cannot win an asymmetrical war. And right now, that’s what we’re in — one side has resources that are virtually unlimited, they have their organizers, they have their strategists, they have their intellectuals, they even have their military. We’re still trying to figure out when they say Critical Race Theory, who are they talking about. Are they talking about us?

Jesse Hagopian: We got our work to do.

Kimberlé Crenshaw: You asked Jesse, what do we have to do? I think we have to wake up to the fact that we can’t outrun this monster. It’s something for all of us. That’s what we learned, how anti-woke turned into Don’t Say Gay, which turned into where we are now. So, number one, there’s no outrunning this. Number two, education is key to democracy. You can’t save democracy without saving education. And now you can’t save education without saving antiracism. They are all one and the same.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Wow. Oh, my goodness, what a moving note to end on. I know I speak for both Jesse and I when I say we could probably ask you questions all day.

Jesse Hagopian: Yeah, I want to be in one of your classes.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: I know, me too. Let’s do it!

Kimberlé Crenshaw: Don’t forget Critical Race Theory Summer School is coming up this summer. Look for us July 30 to August 3.

Ciera Kaler-Jones: Yes, thank you so much for the work that you do, but more importantly, the person that you are. We’re just so appreciative that you created time and space to be here with us so that we could continue to learn. I’m just feeling so fired up and encouraged and moved and frustrated, just holding all of the emotions right now. So thank you. Thank you. We are so, so grateful.

Jesse Hagopian: I’m right there with you, Cierra. I’m feeling all of that, and I want to encourage everyone to pick up some of the work from Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw. Seeing Race Again has been really important for things that I’m writing right now and I think it will help you all. Of course, the Critical Race Theory book. Pick these books up, sign up at the AAPF website, be part of the Truth Be Told Campaign and Freedom to Learn.

Thank you so much for this conversation. We want to give people time to give their feedback on this session, and the content and the format. So, we put a link in the chat so that you can give us feedback on what you learned this evening. But, before we do the evaluation, I want everyone to unmute yourselves and give your thank you’s to Dr. Crenshaw and to each other for your commitment to learning and teaching a people’s history.

Everyone: Thank you so much!

Jesse Hagopian: Thank you. Yes, thank you so much, interpreters.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audiogram

Take just two minutes to listen to Dr. Crenshaw discuss critical race theory and the importance of teaching truthfully about both the past and the present.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

|

COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca The Color Line by Bill Bigelow How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Teach Reconstruction Campaign resources including recommended lessons, films, articles, books, and our national report on the teaching of Reconstruction. |

Books

| Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw has written or edited numerous books, including Seeing Race Again: Countering Colorblindness Across the Disciplines, which was referenced. Other books mentioned in this class include: Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence by Kellie Carter Jackson (University of Pennsylvania Press) I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction by Kidada E. Williams (Bloomsbury Publishing) Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies edited by Kinshasha Holman Conwill and Paul Gardullo (Amistad) with a chapter by Kimberlé Crenshaw. The Movement Made Us: A Father, a Son, and the Legacy of a Freedom Ride by David Dennis Jr. and David J. Dennis Sr. (Harper) Our History Has Always Been Contraband: In Defense of Black Studies edited by Colin Kaepernick, Robin D. G. Kelley, and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor (Haymarket Books and Kaepernick Publishing) |

Articles and Other Resources

|

More than McCarthyism: The Attack on Activism Students Don’t Learn About from Their Textbooks by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series) UCLA’s CRT Forward Tracking Project and Map, a detailed map of laws against history education. African American Policy Forum (AAPF), connecting academics, activists and policymakers in promoting efforts to dismantle structural inequality. A leader of the Books Unbanned and Freedom to Learn campaigns. Freedom to Learn, nationwide coalition of organizations taking coordinated action against school censorship, racial inequity and intolerance. |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

Sept. 9, 1739: The Stono Rebellion March 4, 1877: Hayes Takes Office in 1877 Compromise May 18, 1896: Plessy v. Ferguson Ruling Aug. 21, 1939: Five Black Men Arrested for Going to Publicly Funded Library Dec. 20, 1956: Montgomery Bus Boycott Prevails Jan. 6, 2021: Attempted Coup in the United States |

Participant Reflections

With more than 355 attendees present, nearly 60% of attendees identified as K–12 teachers or teacher educators. The conversation and chat were lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

There was so much!!! How the right is using CRT or “wokeness” as a catchall phrase because they are in the business of whitewashing history.

How right-wing backlash to progress always begins with attacking our ability to learn, because knowledge and critical thinking are essential to progress.

How and why anti-CRT laws have become the Trojan Horse of dismantling truth and equality.

The role of knowledge in fighting oppression.

The importance of education as a laboratory of democracy.

The weaponization of education to discourage liberation and break democracy.

When Dr. Crenshaw connected Reconstruction and the drive to end it to what’s happening today.

The cyclical nature of rights removal by using the argument that marginalized people are asking for preferential treatment when they are asking for safety and democracy.

That the movement is huge. I don’t see a lot of educators in my very white area speaking out about anti-racist teaching. I do hear a lot of white discomfort around making the kids nervous, etc. I feel stronger now that I hear the work going on everywhere.

Connecting Reconstruction to “preferential treatment” rhetoric used today, and naming how the language of “unity” and “divisiveness” is reinforcing white supremacist ideology as a normative world view.

Attacks against CRT and anti-racism are connected to earlier attacks on Reconstruction and the creation of public schools.

Understanding the historical roots of this work and the connection between democracy, knowledge, public education, and liberation struggles.

I was shocked by the minority of the minority being the ones to make changes in the entire country. How few people can affect the masses of us who embrace CRT, etc. Also, the data used to support the arguments made was extremely useful — evidence is necessary to give our students (charts, quotes, graphs, articles, etc.).

What will you do with what you learned?

I feel more confident in the importance of bringing this into my classroom every day. I’m in Kindergarten, so it’s not as much explicit teaching as it is bringing in all the voices. I can make sure all my students feel included and know what it means to be a strong community.

I will teach my students to think for themselves and ask questions. I will also teach them the whole history, not just parts of history.

Learn more. Share more. Answer better.

This class just deepened my commitment to continue teaching African American history, Women and Gender Studies and American history in a way that centers the struggle for liberation.

As an Ethnic Studies professor, I intend to incorporate a deeper understanding of how Reconstruction and the Red Scare have created the scripts for the backlash that we are actively experiencing.

I will incorporate more critical analysis of policy and its impact on our daily lives. I will also be sure to draw more attention to these historical patterns of progress and backlash.

I will not back away from certain conversations just because I teach elementary school. The earlier, the better.

Create a lesson plan on the anti-CRT movement for my students and emphasize the role of the courts in reinforcing Redemption and Lost Cause oppression.

First, talk more to families and colleagues about teaching truth! I also loved the idea of unpacking one of the restrictive laws — I could do this in my Reconstruction unit.

This class affirms my eagerness to teach that we are currently living in the backlash to the Civil Rights Movement, and to help students connect the dots.

I am really wanting to dig more into the connections between the Red Scare and what is happening today.

I want to galvanize more educators and possibly get a group going for Teaching for Black Lives.

As a librarian, keep an eye out for children’s books that are perpetuating concepts (like unity/divisiveness) that normalize patriarchy, white supremacist world views, or are prepping young readers to be comfortable with these false dichotomies.

I think I have started working on the inclusion of power struggles across the curriculum, but feel that incorporating more narratives across time and space would be crucial to help students recognize the power struggles, inequalities, and injustices across different marginalized groups. I feel the need for more resources and materials to teach my students about intersectionality.

I will talk about prison-industrial complex (PIC) abolition in an upcoming talk at my county’s ACLU panel on prison reform. I will include a section on intersectionality, CRT, the right to learn, and teaching anti-racism.

After Party Discussion

The “after party” began when Judy Richardson was spotted in the audience (filling out her evaluation) and invited to join the conversation. She is a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee veteran and Eyes on the Prize series associate producer and education director. Watch the lively conversation in the video below.

Presenters

Kimberlé Crenshaw serves on the Committee on Law and Justice of the National Academies of Science and on the board of the Sundance Institute. Crenshaw has received achievement awards from Planned Parenthood, the National ERA Coalition, and the Outstanding Scholar Award from The Fellows of the American Bar Association (ABF).

She was voted one of the ten most important thinkers in the world by Prospect Magazine. She received the 2021 Ruth Bader Ginsburg Lifetime Achievement Award by the Women’s Section of the Association of American Law Schools. Professor Crenshaw was named the recipient of the 2021 AALS Triennial Award for Lifetime Service to Legal Education and to the Legal Profession. She is a senior non-resident fellow at the Brookings Institute and an inductee to The American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Academy of Political and Social Science.

Cierra Kaler-Jones serves as the first executive director of Rethinking Schools. Cierra is also on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project, which Rethinking Schools coordinates with Teaching for Change, and has hosted many of our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes. Cierra is a teacher, a dancer, a writer, and a researcher. She previously served as director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn