On May 8, 2023, journalist Howard W. French joined Jesse Hagopian to discuss his book, Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War.

This session was the latest in our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss upcoming sessions — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and additional reflections on the session:

It was an astonishingly effective blend of incisive history teaching from a big-picture perspective but woven with the personalization of this history through Howard French’s ancestry and personal experiences, too.

The most impactful part of this class was how Howard French strung together so many stories and historical narratives using the common thread of African genius of agriculture, economy, and innovation across the backdrop of Africa’s rich landscape.

How coffeehouses and newspapers in Europe developed due to sugar plantations in the Caribbean. I never considered this connection before.

How Africa was the center and impetus for so much of what we call our contemporary life.

I was fascinated by the discussion of how European associations with Africa — both through slavery and the sugar trade — provided the fuel for so much of Europe’s technological and cultural advancement. The facts of this story are so clear and it flips the idea of Eurocentrism — which I think all public school history curricula suffer from (see even the beginning of the AP World History curriculum as an example) — so thoroughly on its head that it is ridiculous.

I love how the continent of Africa was centered, along with new ideas to dismantle Eurocentric world history perspectives.

The importance of examining the origins in order to understand current history, understanding the differences in labor systems, the rise of early capitalism and its relation to enslaved people as chattel, as commodity, and the dehumanization of African people throughout history.

That we owe our advanced “civilization” to the sweat and blood of the African Americans who were taken from their homeland or otherwise enslaved and treated like chattel.

I truly appreciated hearing about Howard French’s connection with this history. I feel like we can really be distanced from the content at times, but I thought what he shared was beautiful. I also liked hearing about the Portuguese connection, which I feel is often overlooked.

Thank you so much for continuing to host these! This is the most meaningful professional development that I attend. So much gratitude!

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: I’m very happy to welcome now author Howard French. He’s a career foreign correspondent and global affairs writer, and the author of numerous books, including the award-winning Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War. Howard, welcome. Thanks so much for being with us today.

Howard French: Thank you so much, Jesse. It’s great to be with you and with all of you, and thank you to the interpreter as well.

Jesse Hagopian: No doubt. Well, I’m just so glad you wrote this book. I learned so much and greatly enjoyed your prose and your ideas. It just sparked so many ideas for me about how I want to use this in my classroom, and I think it will for many educators with us today, as well. Most of us learned in school that modernity was the project and product of European exploration, and that Africa was a barrier to this exploration, an obstacle to the trade routes that they sought to establish with Asia. I think back to the great historian, Arturo Schomburg, when he was in grade school and asked his teacher if they could learn about African history, and the teacher replied by saying that Black people have no history, something that you hear echoing in the words of Ron DeSantis today. But I was hoping you could talk about the major Eurocentric master narratives that students often learn about Africa, and the truth, really, about the sophisticated societies of Africa that Europeans encountered in the 1400s, including Mansa Musa’s legendary city of Timbuktu in Mali, and so much more. So, take it away.

Howard French: Well, there’s an awful lot to unpack in there and already I’m worried about 25 minutes before the breakout rooms. But I guess I’ll start where you started, and that is this notion of how the age of exploration began. And my book starts there, as well. It starts there for a very deliberate reason. Actually, the very first sentence of the book says a history can’t end up in the right place if it doesn’t begin in the right place. So the age of exploration in the way that it is almost always taught begins in our curricula, and in most of our history books, with this idea that Iberians and most particularly Portuguese in the 15th century were hell-bound to get to Asia by sea. And, as you said in your own phrasing, Africa was seen really as an obstacle to that. The challenge that Africa presented was its size, and the difficulties it presented in circumnavigating. The Europeans literally didn’t know if Africa could be circumnavigated; they didn’t have a very good understanding of the global oceans yet. And so that was the big mystery: can we even get around Africa? So Africa was standing there as a problem.

Africa is presented in the beginning of the way this history is told either in two ways: as a problem or via its absence. So, this is the binary in the way the teaching of this era is done. Sometimes, just to save time so to speak, Africa is not mentioned at all. Other times, it’s presented as a problem. And we have these ingenious navigators who are trying to figure out how to overcome the problem so that they can get to Asia by sea. The reality is — and I’ll try to do this really quickly — that more than 150 years before Columbus crossed the Atlantic, there was an empire of the Sahelian region of West Africa, just beneath the Sahara, called Mali. The succession of emperors of that empire were themselves obsessed with ocean navigation and with discovery and with figuring out what lies on the other side of the great sea that is off of their coasts. I’m calling it the great sea; we know that sea as the Atlantic, of course. They were not trying to get to Asia; they didn’t have Asia in mind. But Mali was a gold superpower of that age. Most of the gold that entered into Europe transmitted North African kingdoms into Europe, mostly Italy, but also in Spain and Portugal. And so the Europeans wanted to figure out where the gold was coming from, and the spark that drove their curiosity much more than anything else — and the spark that I believe and argue is sort of the starting point the the ignition point of the age of exploration — is the pilgrimage that this emperor Mansa Musa, who you mentioned, made to Cairo and to Mecca in 1326 and 1327, in which he carried with him 18 tons of pure gold in gold bullion and gold bars. Mansa Musa distributed that in patronage throughout his route, and especially in Cairo, all of that gold. In fact, he gave away all 18 tons and the monetary and economic impact of this act of largesse of Mansa Musa’s was to depress the price of gold in what were for Europeans understood to be the world markets for gold.

So the price of gold collapses, virtually. Silver becomes worth much more than gold, which is usually the opposite in terms of their ratios. And the Europeans then spend a succession of decades — and the Portuguese take the lead in this — trying to figure out, they knew the gold came from Africa, but they didn’t have a sense of where in Africa, that it was always transiting through the hands of the Berbers in North Africa. The Portuguese wanted to overcome the middlemen of the Berbers and figure out where the gold came from.

By the way, there’s an interesting symmetry going on here. Mansa Musa’s predecessor, who launched two attempts to cross the Atlantic Ocean in the 1310s, was also trying to overcome the middlemen. He was not trying to sell gold to the Europeans — he was sick of selling gold, having the North Africans take a big cut in the gold — and so therefore wondered, can we find societies on the other side of the ocean that would also like to be gold? Everyone basically understood it’s the most universal store of value that humans know, and so it was a very reasonable supposition that he had, that if we can just cross the water there must be land somewhere on the other side. If we find societies there that want to trade, we can use our gold superpower with them and not suffer the cut that you take via middlemen.

Europeans had no time in the way, and Americans, in the way we have subsequently much later told this history. But, the facts that I discovered in the research of this book — and in fact the thing that set me on the course that led to me writing this book — was a discovery in the archives working on a book about China. Reading into European context with China in the 16th century and discovering when — if you’re a curious researcher you will always discover things that you were not looking for — so I’m looking into stuff in the 16th century and I find accounts of the Portuguese in the 15th century, where they’re not trying to get to Asia at all. They’re writing contemporaneously. It’s crystal clear. Our obsession is with Africa, we are spending decades trying to understand Africa, trying to come to terms with what we’re finding in Africa, and most of all, trying to trade with Africa, trade for gold for most of this time span. Then, eventually, but only toward the end of the time span — we’re talking about meaning from the early-mid 1400s until the last years of that century — it’s only then that trafficking human beings begins to take place, and even then still on a pretty small scale. So the Europeans tell this story, cutting the Africa piece out, and that’s unfortunate for a number of reasons. Not just because it takes credit away from Africa for having been the spark of the age of exploration, but also because the processes that led to slavery, and which ultimately flowed from this, are the very economic processes that made Europe rich, that drove Europe’s economic divergence in wealth from China and India and other parts of the world, and enabled Europeans to so-called settle the western hemisphere, the Americas, and to make their settlement of the Americas economically viable and ultimately extraordinarily profitable. All of that stuff flowed from Africa. So when you’re cutting Africa out of the story, ultimately you’re not just cutting the proper beginning out of the story, but you’re cutting the end of the story out of the story, too. You’re making it seem like Africa was not just inconsequential — because it was just an inert barrier for a faraway objective like reaching Asia — but Africa really wasn’t of any economic consequence for Europeans, or subsequently for the West, when in fact Africa was everything economically for the West.

Jesse Hagopian: That’s so right. That’s so powerful. That’s the world history education I wish that I had. I know that so many of us are going to use your framework to help redesign our world history courses, our Africa history courses, our American history courses. I just love the way you flip the script and show that modernity is a product of African ingenuity and exploration, from Mansa Musa’s hajj to Abubakr’s exploration of the Atlantic. These are just left out of too many conversations, so thank you for putting them back in. You start your book in 1471, when the Portuguese crown established Europe’s first overseas outpost in the tropics of Elmina in present day Ghana, so I was hoping you could tell us more about Elmina and about how Portugal became the first European nation to establish that outpost in West Africa.

Howard French: Sure. This was all the result of a multi-decade obsession that was forged in the mind of a member of the Portuguese ruling family, a prince — not a crown prince, a crown prince means somebody who’s going to become king. But this man, because he was the third son of the king, he knew he was not going to become king, and so they had to give him something to do. So they put him in charge of a branch of the Roman Catholic Church, the Order of Christ it was called, in Portugal, and they also eventually gave him the task of leading explorations. So this person, who we know as Henry the Navigator, becomes completely taken with this idea of connecting with Africa. He starts in the 1430s, in pursuit of the source of gold that he believes is flowing from Mali — and with the limitations of European technology in this era, sailing methods and the nature of European ships in this era, and understanding of geography in this era — this is a very arduous task. Some years they could only advance 100 or 200 miles down the coast further than their last for this point of exploration. So this begins in the 1430s, [and] by the 1460s — pardon me, I can’t remember the exact year I think 1467 perhaps — Henry the Navigator finally dies.

But the Portuguese didn’t give up. It’s interesting to understand why they didn’t abandon this mission. All along that way, from the 1430s to the 1460s, they had not found huge amounts of gold yet. They knew there were huge amounts of gold, but they hadn’t found it. So, why did they continue? Or another way of asking this to be just deliberately provocative — Why didn’t they just give up on Africa and try to get to Asia, which is what we’ve been taught anyway? Which they definitely didn’t do. They didn’t give up because the Ottomans had taken over — Ottomans being a Muslim empire — had taken over the western reaches of the Silk Road. The Ottomans owned control of what is now Turkey and what is now Egypt and what are now Syria, and many other parts of what we sometimes call the Middle East. These modern day country names that I’ve given you are places that sit aside the western terminus of the Silk Road.

Trade along the Silk Road was, had long been, one of the most reliable and lucrative sources of commercial wealth for southern Europeans. The Spanish had a window onto the Mediterranean, the Italians had a window onto the Mediterranean, the Greeks had a window onto the Mediterranean. But the Portuguese, if you look at the Iberian Peninsula, the Portuguese have just the western shoulder of Iberia. None of their territory sits on the Mediterranean. So the Portuguese were completely cut out of that circuit of trade, and they had a very special motive, beyond what drove Spanish exploration or Italian exploration to try to find alternative sources of wealth once the Silk Road circuit began to dry up for southern Europe. This pushed the Portuguese out into the sea looking for other places they could trade with, and particularly with this central obsession of connecting with Africa.

So, Henry the Navigator dies in, I think, 1467. Don’t quote me on that, but it’s definitely in the 1460s. The Avis dynasty, of which he was a member, pursued this goal until 1471. Poor guy, he died a little bit before they found gold. They didn’t find the Malian gold initially, they found similarly immense quantities of gold in what is present-day Ghana. They named the place where they anchored their boats Elmina, which means in Portuguese “the mine.” They knew that they had discovered gold there because when they came ashore at this place — which is a beautiful sheltered bay that is sort of a crescent, and there’s no rough waves there. It was a safe place. They didn’t know there was going to be gold there. They were coming ashore to get water and food and stuff like that, and they see ordinary people, everybody has gold jewelry, lots of gold jewelry, and they said, “This surely must be significant.” It didn’t take very long for them to scratch around enough to understand that, in fact, there was a very large trade in gold available there. I described this in great detail in my book, but I can’t really give you the long version of this.

But long story short, they end up negotiating with the Logo king of a modest kingdom that controls the area right around that bay, and they obtained his permission to build a fort. This was the first fortified structure that Europeans ever built anywhere in the world outside of Europe, and it stands up until this moment. There are photographs of it in the book. It is enormous. The fact that it was built to such a high standard of robustness and permanence tells you how important this was for the Portuguese. I’ve been there many times. I went there for this book, but I had been there for the first time as quite a young man. The place was built to stand the test of time, and it has done that. The reason for that is because the Portuguese had obtained — within the space of three years of trading with this relatively small kingdom that controlled just that immediate local area — the Portuguese had earned enough income so that Elmina itself constituted one third of the total national treasury for the Portuguese crown. This was such a boon for the Portuguese, for the Avis dynasty, that they named their national treasury the House of Africa. The literal phrase was this is the House of Guinea, Guinea was their word for Africa, for Black Africa. They named their treasury the House of Black Africa. This is in the 60s and 70s.

Nobody’s rushing on to Asia yet. The Portuguese and the Spanish being so closely related linguistically and historically speaking, the Spanish get wind of this very quickly. Spain’s much larger, ten times bigger than Portugal. The Spanish sent their navy down the coast of west Africa, determined to seize this place away from the Portuguese. But again, the Portuguese and the Spanish having such deep connections, the Portuguese had intelligence about the Spanish intentions, and they ambushed the Spanish fleet and sunk most of the ships. It is at that point that the Portuguese decided to build this fort, which stands today, and which totally revolutionized world history.

You didn’t ask me this question, but I think this is really important to explain. So up until that point, Portugal had been among the most marginal players of nations that still exists today that you can list in Western Europe. It was extremely poor. It was a recent creation. The obvious dynasty had broken off from what I’ll call proto-Spain, meaning the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, and had declared its independence from them. But it had almost no means of its own. It was almost reckless for them to go to war with the Spanish. They were so poor, all they had was cork and salt and dried fish as trade items. Within three years one third of their total, and it would increase beyond this, but one third of their total trade now is from Elmina, this one place on the coast of West Africa. And this is what gave the Portuguese the wherewithal now to begin building ships that created all of the subsequent history with which all of you will be familiar, and even your students will be largely familiar with the discovery of the Americas, the Portuguese discovery of Brazil, much subsequent voyages into Asia. All of the money that was needed to launch those efforts came out of these connections with Elmina — this is the motor of all of this history.

And I’ll just say, finally, with regard to Columbus, because I think this is a particularly opportune thing to teach every high school student. By high school you’ve learned about Columbus, right? Everybody’s got to learn something about Columbus, right? Columbus got the support of the Catholic rulers, they were called los Reyes Católicos in Spanish, Isabella and Ferdinand. He got his funding to launch his three ships with 85 men to try to prove that there was land on the other side of the Atlantic because the Portuguese had found gold in Elmina. That’s the reason the Spanish funded him. We never learned that.

Christopher Columbus had been laughed out of one royal court after another. They told him, “This idea of yours sounds very eccentric, like the world is round. And if we only go west, we’ll hit Japan. And right after Japan, there’s China. And we can establish trade for tea and silk and all of these wonderful things,” and happily ever after, right? Poor Columbus went all over the place trying to get people to fund him, to try to prove this concept, and he had been serially refused by one court after another after another after another. When the Portuguese discovered gold in Elmina the Spanish decided to fund Columbus’s first voyage, which is for most people the starting point of the modern age. And they did so because they had a theory, kind of a geological theory, that said if the Portuguese have discovered gold in the tropics, that must mean that the tropics is where gold is distributed in the world. So we’re not really sure about all this other stuff that Christopher Columbus is talking about, like you’ll get to Japan and the Earth is round. Maybe that’s true, maybe it’s not, but that’s not really what interests us. Our interest is making sure that the Portuguese don’t get all the gold in the world because they’re in the tropics in West Africa and we are not. So let’s fund this guy, Christopher Columbus, and see what happens. And what you very quickly see if you read Columbus’s diaries, literally every day on his first voyage he notes what he has found about the presence of gold. He knew what his marching orders were, his marching orders from his patrons was to go off and see if you can match the Portuguese.

Jesse Hagopian: I read that diary. It’s incredible.

Howard French: So even Columbus’s discoveries flow, not indirectly, but directly from Elmina.

Jesse Hagopian: Yeah, thank you so much. It’s incredible to see how much the wealth of Africa is the generator of European exploration. And we have a whole campaign at the Zinn Education Project around abolishing Columbus Day and replacing it with Indigenous Peoples’ Day and teaching the truth about Indigenous people. So, that all fits really well for a lot of the work that we’ve been doing. We’ve also been working on these laws that are placing educational gag orders on teachers about racism, and those who are passing those laws trying to stop teachers from teaching about systemic racism often claim that teaching the true history of slavery means teaching that Africans enslaved each other before Europeans and that the U.S. and Europe were the people that ended slavery. I think that it’s important that we understand that history better and teach it better. So, I was hoping you could explain what’s wrong with this narrative and describe the toll of European enslavement on Africa.

Howard French: Wow, that’s a big question. So, first of all, there’s like six different things I want to come at here. First of all, I want to speak to Asia, and this gets to the whole political movement that you’re asking me about. It doesn’t besmirch any part of the world to try to capture the truth of what was really going on with regard to that geography or with regard to human contact between another part of a world and the part of the world you’re talking about. I have said to you today — and in my book — that Asia was not the driver of this history. That doesn’t mean Asia doesn’t have a great history, or that the eventual connection that Europeans made with Asia was not also important. In many ways it really was. This isn’t your problem, but I think this helps illustrate the problem with this kind of blinkered political thinking — if you say this about one place that means you’re sort of taking something away from them, or being unfair to them or revising things in a politically correct way. Correct is right, politically correct is wrong.

So, with regard to slavery, slavery has existed as best we know in every part of the world from time immemorial. Right? Let’s just start there. There was slavery, indisputably, among white people in Europe simultaneous with the early parts of the Transatlantic slave trade. Slavery is a thing that human beings have been doing to each other for a very long time. Now, slavery is also a very complicated and highly varied institution. Its characteristics have been different in different places and in different times. This is not going to be a lecture about all of the many variants of enslavement.

It’s important, for your question, to ask, and this is something that the people who like to emphasize, “Well, didn’t Africans enslave each other” as a way of brushing this to the side, or minimizing the importance of what this meant to our history and to millions of people. What was different about African slavery at the hands of Europeans is that African slavery represented a form of beastialization. The common word used to capture that is chattel. Chattel comes from the Latin word cattle. Africans under European control in the Transatlantic slave trade were being reduced or being deprived of their humanity.

The famous sociologist Orlando Patterson said, “From the moment of enslavement in chattel arrangements, they cease to be social beings.” What does that mean, they ceased being social beings? That meant that their social relations were no longer recognized by their owners. What does this mean? This means that a husband doesn’t have a wife, that there’s no record of wife and husband. The owner doesn’t care about any of that. The only relationship is: I own you and I own her. You don’t have anything to say about that. I’m the owner, you are my cattle. When you are being deprived of your social existence it means if I’m a mother or a father and I have a child under enslavement my enslavers have no duty to recognize my paternal or maternal relationship with my offspring. I don’t have any rights of parentage over my offspring. Those people are like foal cattle — they came out of the cow and now they’re just going to be fattened enough until they can produce milk or be eaten as beef. It’s reducing people to the state of animals.

That was chattel slavery. And it was for the very specific purpose of being put to work in plantation agriculture, which was a new economic institution that was born, I argue, on a tiny island off the coast of central Africa called São Tomé in the 1480s. The Europeans worked out, for the purpose of producing sugar from sugar cane in commercial quantities, how to organize large numbers of chattel — meaning enslaved Africans in enclosed settings under regimental work orders — with the very explicit notion that they would be worked to death. There was no value placed on the preservation or the prolonging of their life, they were just like tools that were expected to be worn out after a certain period of time. And as an ordinary cost of doing business, they would be replaced once that happened. So, how to keep a plantation going was, in part, from the perspective of the enslaver, understanding supply. I have to keep resupplying myself in cattle, we say chattel, but keep resupplying myself in chattel so that I can keep my production up. These were entirely new arrangements in human history.

These sorts of arrangements have never happened or existed anywhere else on anything like the scale that we’re talking about. They have also never existed anywhere in human history on the sole and exclusive basis of race. This is another totally novel feature of this time. So Africans had slaves; yes, they did. Slaves existed in China; yes, they did. There were slaves among Native Americans before white people arrived; yes, there were. There were slaves among Aborigines; yes, there were. There have been slaves here, there have been slaves there. Russians had slaves, Swedish people had slaves. These are all true facts. But nobody else had chattel slavery on an industrial scale — which was established with an explicit and unique racial foundation, which said that the fact of your Blackness is a license for us to turn you into cattle. That was a new arrangement in human history. I could go on, if you’d like to talk about this more about many other dimensions of why African slavery was different, but I think what I’ve said so far is the most fundamental thing that students need to understand.

Jesse Hagopian: Thank you so much for setting the record straight on that. I think it will really help educators here teach this period of enslavement with more accuracy and take on some of the myths that are being spread. We just have a minute before we break, allowing teachers time to discuss these ideas amongst themselves and think about how they might put them in their classroom. But I thought I’d just follow up very quickly on that question about your chapter titled Capitalism’s Big Jolt, where you write about the role of Africans creating European wealth and the first global commodity of sugar, which is very linked to the discussion we were just having and how, particularly in Haiti and Barbados, that commodity became so valuable. You’ve been talking about how Barbados’s sugar export was more lucrative than all of Spain’s colonies. I couldn’t believe that. I was just fascinated by your treatment of how African labor transformed sugarcane into the commodity of sugar. I was wondering if you could just briefly say how sugar helped to transform the political economy of Europe and the cultural practices, which also was fascinating to me, these cultural practices of modernity that are brought in with the sugar trade as well.

Howard French: Okay, so sugar. What should be said first is that before the early 16th century the Portuguese sugar plantations and chattel slavery — by the way, I call plantations prison industrial complexes, and I will probably lapse into it with you later as we continue this conversation, into saying plantation because it’s a quick, one word description. But I think it’s a euphemism. I think that what we’re really talking about is a prison complex where people are deprived of their social existence and worked to death, and plantation doesn’t give you all of those connotations. Anyway, these arrangements were invented and perfected in São Tomé. In 1501, the Portuguese discovered, quite by accident, Brazil. Brazil and São Tomé have pretty much the same ecological and climate setup, so the Portuguese were very quickly able to move sugar production across the ocean into Brazil.

The Portuguese had started out being interested in gold, but sugar cane was green gold. Sugar was the most lucrative commodity in the world economy; for at least three hundred years nothing was even remotely as profitable as sugar. And once the Portuguese had worked out how to produce it in an efficient way, using chattel in a prison industrial setting, it transits the Atlantic, and by the 1570s, the Portuguese were no longer trying to turn Native Americans in Brazil into chattel. They spent several decades trying to do that. It failed for a variety of reasons, the single most important one is epidemiology. The native populations of Brazil didn’t have resistance to European diseases, so they died in extraordinary numbers every time the Portuguese tried to corral them into one centralized location. By the 1470s, all of Portugal’s sugar production in Brazil had been Africanized, meaning the work was being done by chattel, enslaved people.

In 1630, the English took over the island of Barbados, which had been sort of neglected by the Spanish. The Spanish controlled all of the Caribbean that they were interested in. And I say “interested in” because the Caribbean has a huge number of islands, but the Spanish attention span was limited. Spain had these big places like Cuba, Hispaniola, which is where the Dominican Republic and Haiti are, and Jamaica, which are all, by the standards of the Caribbean, quite big islands. The Spanish really didn’t care about the smaller islands because the big islands were such a mouthful for them. So this created an opening for the English first, and then the French secondly, to take over some of the small islands in the eastern Caribbean, as you near continental South America. In 1630, the English brought some Africans, almost immediately actually, they’re Africans on the first English ship that arrived in Barbados. They have been captured at sea. The English attacked a Portuguese ship that had enslaved Africans on it, and the English took over those chattel and put them to work in Barbados. But in the first two decades of English experience in Barbados, which from the very start was aimed at producing sugar, the English tried to copy the Portuguese methods in Brazil, but by using mostly indentured servants from England. They gave up on that by the 1650s. They started phasing out indentured servants and bringing more and more people from Africa, to the point where in the 1660s almost no white people were doing labor on sugar plantations. There’s that word plantation, right? Prison complex. And it was all Africans.

Between 1660 and the end of that century, this is the period in which I said England made more money from sugar than Spain made. Spain’s Pizarro [Francisco Pizarro González] sent 1,800 men into the highlands of the Inca empire in South America and took over the heartland of the Incas and stole all of their gold and silver and whatever else they could find. Many of us learn this in high school even now, right? You have these fantastic visions of incredible white capacity and bravery. You’ve got a band of white men and they’re striding and they conquer an empire, and you also have these visions of enormous amounts of wealth — and enormous amounts of wealth were indeed stolen. The Spanish had to invent new classes of ships called galleons, which have these enormous fat bellies, in order to carry off all of the loot that they stole from the Incas, and later also from the Aztecs.

But your question really is about the impact on Europe itself, and so I’ll turn to that. By the end of the 1600s sugar — because of the enormous output of Barbados, an island that is one third the size of Los Angeles, one sixth the size of Long Island — the English had made more money from sugar production than the Spanish had made in conquest and in looting [combined]. Just think about that: the English, bringing in and working to death large numbers of Africans to produce sugar, earn more money than all of that gold and silver taken by Spain from Mexico and from Bolivia and Peru. It’s an incredible thing. That’s incredible enough on the face of it. If we didn’t learn anything more about this, this would already be a stunning thing to teach high school students. There’s something even more stunning, and that is what happened to Europe. This changes everything in Europe. It changed life in Europe altogether, and here’s how.

So, Europeans up until that point — not because Europeans are stupid or lacking in enterprises. I’m just going to tell you the truth. Europeans did not have hygienic sources of water; most of the time, for most people back in that era, no human beings that I’m aware of actually had a scientific understanding of hygiene yet. In other words, a theory of bacteria and things like that. So the Europeans, the English — let’s just stick to the English because they were the first to to tap this source of wealth in Barbados, and then revolutionize their own society — the English begin to invent ways of consuming sugar infused drinks that allow them no longer to a) have to drink in salubrious water, meaning water that’s going to make you sick, or b) do what most people did in the workplace, and that is drink ale throughout the day. English people had small workshops. They didn’t have factories yet, they had small sized workshops, small units of production for anything that resembled anything remotely industrial. Two, five, eight, ten people working together in a place, and you get thirsty to drink ale. Tea wasn’t there yet, coffee wasn’t there yet, clean water wasn’t there, and so you drink ale. And as you can all anticipate what happens when you begin to drink ale at 10 o’clock in the morning and you’re trying to work by two o’clock in the afternoon, if not earlier, your productivity is going to start going way down, right? You’re drinking ale, even if you’re a disciplined person, you’re not drinking to get drunk, but it’s still ale.

So, in 1630, the English take over Barbados, [and] by 1660, Barbados is really booming, and the workforce is entirely African. Sugar is no longer the extraordinarily rare commodity that it had been historically, up until that point. It has become so abundant now that it’s entering the common diet and it’s becoming cheap and universally available. This allows the English to begin to consume a variety of other products — also produced through chattel slavery — like coffee, which changes everything. So, English people, even down to this moment, they want to drink sugar in their coffee. The English are famous for that: They put milk and sugar in their coffee, right? So they’re drinking coffee in the daytime sweetened with sugar. What does this do? Not only are they not drunk, but they are also stimulated, and they’re getting these extra calories from the coffee so they’re not needing to break to eat as much because they’re getting extra calories. Sugar is a calorie boost. This is the jolt that I talked about, the name of this chapter. Cheap Sugar may not be good for you in the long run, people didn’t know that until probably fifty years ago, but it sure does get you going. So, you have cheap sugar and you have caffeine, and worker productivity is going through the roof for the first time in European history. This is revolutionizing productivity in Europe. And then one other thing begins to happen . . .

Jesse Hagopian: We’re going to have to move very quickly with this one, because I love this story.

Howard French: The one other thing I have to emphasize is the invention of the coffee shop. Some brilliant, unknown person in Oxford, England near 1650 opened a coffee shop on this understanding that coffee is a stimulant and probably addictive. You put sugar in it and people will want to drink it. Next thing you know, boom, it’s so successful that coffee shops are all over England in a very short period of time. This gives way to another entrepreneurial idea: That we’ve got this captive audience, not like a tavern where everybody’s drinking ale, but they’re sitting around drinking coffee with sugar in it. Their minds are stimulated, they’re probably smoking tobacco — another slave product which also reduces your appetite and stimulates you — and they’re talking now very soberly about the affairs of the day. What’s happening in Parliament? Did you hear about the ship that came in from Antwerp today? What’s happening in the Catholic Church, or between the Catholics and the Protestants?

And some clever cat says, “You know, I bet if I can create a bill, I mean a sheet of paper with printed news on it, word of what the discussion is today in Parliament and shipping news and things like that, people in these stimulated environments will want to buy it.” This is the birth of the newspaper. This is the birth of the very notion of citizenry, from which democracy is built. Citizenry means, at the most basic level, an assumption that you have rights of all kinds. But most pertinent to this conversation, a right to knowledge about what is taking place in your society, and from that flows a right to say about what is taking place in your society. All of these things flow from the prison industrial complex, from chattel slavery, from the capture of Africans by the millions to be put into these productive purposes, which then place Europe on an entirely different trajectory from the rest of the world. I’m going to close, I promise. We understand these things simply as the fruits of European ingenuity. It’s the scientific method, it’s Judeo-Christian this or that. We find all of these self-flattering ways of describing the origins of these things and we leave out of the picture the most obvious fundamentals of how these things happen. These things happen out of the sweat and the blood of human beings from Africa.

Jesse Hagopian: Wow, thank you for breaking that all down for us. We’re about to head into breakout rooms so teachers can chew on all that you gave us there.

Before the break, we had such a rich discussion about African societies, and about the impact of enslavement. I just want to follow up, Howard, on a question about how we talk about enslavement. Often, when we’re teaching students about enslavement, we focus on how slave labor was used and we talk about the stolen labor, or enslaved people built this country even. But, oftentimes the intellectual labor of African people is erased and we reduce Africans just to their physical attributes, not including their skills in science, including cooking and agriculture, astronomy, geography, math, carpentry, medicine, midwifery, problem solving, art, languages, and so much more. Erasing these references, I think, does profound damage to our understanding of world history, of African history, and it contributes to stereotyping Black people today. So I was hoping you could address that.

Howard French: Thank you, Jesse, and welcome back, everyone. Before I do that, I want to just say how much I appreciate all of you. I come from a family of teachers. The reason I accepted to do this — I don’t expect you to be impressed, but I am an extraordinarily overworked person. I’m over committed, I have too much stuff to do already by a factor of whatever — but I couldn’t say no to you guys because I know how important what you do is. And I can feel the spirit in just the little exchange of comments I heard just now and it’s really beautiful. So thank you.

On your question, Jesse, I want to be really careful. You said what you said probably better than I could say it. You listed all these domains in which African people and people of African descent made contributions that stemmed from sophisticated thought processes, and this aspect of African life and of African diasporic life is systematically stripped from the record, or from the emphasis, the thrust of how we teach and learn history. I believe that profoundly. I completely agree with you. But I also think that there is no reason — I don’t think you were suggesting this but I want to be careful — to insist that we should never minimize or feel bad about the fact that blood, sweat and tears, physical labor, physical hardship, being worked as animals, actually constituted the motor of development that created the West and the wealth of the West. It doesn’t mean you were stupid, it doesn’t strip away all those other things, I just want to make sure that, politically, I don’t feel the need to say, “Well, okay, it wasn’t just this, it wasn’t just that.” This is the Himalayas, this is like the biggest thing you can think of already!

Now to your question when we started this conversation, how did you know they were hellbent on getting to Asia? Well, they eventually got to Asia because they had a Black navigator that they got from the Swahili coast of Mozambique who already knew the trade routes to India. That’s how they figured out how to get to India. They figured out how to produce sugar in Brazil because of the African captives demonstrating from specialized knowledge that they had gained in their own lives, in their Indigenous cultures, about soils, about irrigation, about planting, timing of planting and harvesting tropical crops. They had not grown commercial sugar before, but they had a lot of carefully built-up knowledge, accumulated over time, that made them indispensable as knowledge workers.

I talked about in my book the fact that it takes three, four, five decades before Africans totally displaced Native Americans in Brazil as the workforce in the prison industrial labor complexes. But in the early decades, the African workers were a very small minority being used by the Portuguese, and they were almost exclusively being used in knowledge roles. They were specialists in various things. You can go from one place to another. When South Carolina — or the Carolinas [as] initially one place — was formed as a colony, what did South Carolina subsist on or what was the nature of their economy? It was a rice growing economy. The white people in the plantation economy figured out how to grow rice in a profitable way because of the agricultural science that the people from a specific part of Africa had developed to a very high degree. The specific part of Africa we’re talking about is modern day Guinea and Guinea Bissau. The white people who were looking for slaves to grow sugar were deliberately sourcing slaves for rice agriculture there because the people from those cultures knew vastly more about rice cultivation than white people did at this time. This story is everywhere, in every page and every chapter, right? And again, you’re not doing this. But nobody needs to apologize for saying, like, “Yeah, our labor is the thing that made all of this stuff happen and all of this stuff work.” That’s what happened. That’s a fact. And it’s never been adequately recognized. So I’m not going to let go of that.

Jesse Hagopian: Thank you for centering that and framing it that way. Also, just when we were talking about contributions that African people made, including their labor, but beyond, my jaw just dropped when I was reading your book and I discovered that we both had something in common — that we became blues fanatics in high school. I started playing jazz and blues in Oregon, and then harmonica. And we both idolized Jimi Hendrix, who actually went to my high school, Garfield High School in Seattle, where I teach, as well. Where I’ve taught for over a decade.

I love how you describe the art form of the blues and jazz and the significance of its origins in Africa, and you describe how you deepened your appreciation for the blues on your trip to Mississippi and the Mississippi Delta region. I’m going to Mississippi for the first time at the end of the month to see the plantation — or better put, as you say, the prison industrial complex — where my family was enslaved. I’m going to see that place and to learn about the blues, and I just love that you included the artistic contributions of African peoples as well.

Howard French: Thank you. Listen, this is a statement that the politically correct people will have a problem with. It is not only Africans and the people who descend from Africans that we call African Americans, but to a very, very large extent, it is the culture of those people that make Americans American. That’s where America came from, culturally speaking. That’s an enormous part, a disproportionately large part, of why Americans are different from English people or from other Europeans. There’s a quote in the book, if you look in the index, excuse me, I’m not going to mangle it. She said it better. She said everything better than I could ever say it. But Toni Morrison talks about how you have the food and you have the pot. African Americans were the pot that made the dish of American culture. Look up the quote itself [“black people are not in the melting pot, they are the pot” from The Bluest Eye]. We are the cauldron out of which all of this stuff, culturally speaking, emerged. So, this is another leaf.

And you said, “What about the intellectual contribution?” Okay, now we’re on to the cultural side. There is no American culture without African Americans. It’s not even imaginable, that’s how absolute we’re talking. It’s not even imaginable. Americans who have no African ancestry, who never think about Africa, are not even aware of Africa or of this cultural conversation, are themselves all profoundly shaped by Africa and by the cultural input of those of us who descend from Africa. This is what makes America America.

So, the blues is kind of a cornerstone in that because of the particular history of the blues, where it emerges from work songs, the field, the Mississippi valley at a time when cotton supplants sugar as the most important commodity in the world, and becomes not the engine of Europe’s take off and divergence from Asia in terms of wealth, but America’s take off and divergence from Europe in terms of wealth. That happens all there and blues is the substrate, it’s the language, musically speaking and verbally, that people of African descent are developing as a way of communicating explicitly to each other and in a mode of subversion. We have a language where we can talk, idiom and metaphor, where it’s not necessarily going to be understood in the way that we understand it, and we can have our privacy even in public that way. This is how the news comes about.

Jesse Hagopian: You got me hyped to get down there now. I’m going to be on the phone with my dad after this telling them how excited I am to go and join him down there. So thank you for that. We just have probably two minutes to wrap before we have to move to the evaluation that I hope everyone will fill out. So, I just wanted to end by thanking you for writing this book. It just demonstrates so clearly that you spent years of your life researching and writing this extraordinary telling of African history and its role in making the modern world. In reading your book it really appeared to me that the immense labor you put into reinterpreting Africans’ role in world history is both an intellectual pursuit of striving to get the narrative — that’s been horribly mangled by Eurocentric narratives — but also it appeared to be a deeply personal pursuit as well. I just wanted to appreciate the way you connect the history about your own life and the significance you tell about your family story. I thought maybe you could just tell us about your enslaved ancestors in Virginia and your connection to Ghana, in West Africa, in the last two minutes.

Howard French: Sure. Thank you. So my parents, both of whom have passed, both descended from slavery. But the story I tell is about my mother’s paternal family. I cover 600 years of history in this book and four continents and the entire world of the Atlantic. There’s a lot. I grew up knowing the story I’m about to share with you and I knew how important this story I’m going to share with you was to enlivening me to this subject and to making me want to know more and giving me the strength to pursue the research that I pursued. But I was also wary [because] I’ve got 600 years here and all of this ground to cover, I don’t want to turn this into a book that is in any way self-indulgent or about me. So it really doesn’t come up. The Virginia story doesn’t really come up until almost the end of the book.

The story, in a nutshell, is this that my grandmother’s grandmother was purchased by the governor of Virginia, a man named James Barbour, who was a close friend of Thomas Jefferson’s and who eventually occupied very high posts in the government of Thomas Jefferson and subsequent administrations. He was minister of war, he was secretary of state, his brother, not my immediate blood relatives but the brother of my immediate blood relative, was the Supreme Court justice on the Dred Scott decision case court. Anyway, this grandmother’s grandmother was purchased off the boat from Africa by James Barbour, and James Barbour took a liking to her. James Barbour did not write a diary that has been passed down across generations for us to know what he was thinking, but we know for sure that he had children by her who became my ancestors — and we can only imagine the contours of their, “relationship.” We can’t really know for sure. I think the default has to be, when you’re talking about an enslaved person, a woman, that she is not really in a position actually to give consent under those circumstances, but we simply don’t really know all the facts.

Anyway, she bore this man two sons. One of them is my direct ancestor, and the other one is a great, great, great, whatever uncle. And she extracted from him, James Barbour, a promise that he would take care of his her sons in his will. In fact, before he died, well before he died, he also took a liking to these two young men, and in an era when it was literally illegal to do so, he allowed these Black young men to have a school education, to learn how to read and to write and to develop a trade. One of them became a shoemaker, and the other one became an ironworker. So, James Barbour leaves them in his will, then he dies and James Barbour’s white children go to court to excise them from his will, to cut them out of their inheritance — which was intended to be a not insignificant amount of property from the very large estate James Barbour left. And these two men, my great, great, great grandfather and his brother, made it their life’s mission then not to slink away in defeat but to save money and to work hard, and little by little, to cobble together whatever parcels of property they could from that vast domain by purchasing what was their birthright and passing it on to their children. And that land, what remains, that land is still in my family. I grew up spending time as a child hearing these stories and being aware, in this extremely personal way, about what slavery was, what it meant, what it did to people, how it shaped me, how this was just everywhere. I’m actually blessed to have had . . . we don’t choose who our ancestors were and that’s not what I’m talking about, but blessed by way of this experience to have had parents who talked to me and my siblings at a very young age about all of these things in their full complexity and in a sophisticated way. So that is one of the most important germs, if you will, of this book, even though I don’t spend a lot of pages talking about it.

Jesse Hagopian: No, I really appreciate that. Thank you so much for sharing that story and for enlightening us all. Everybody should pick up the book. Make sure this is the cornerstone of your teaching of African and world history, Born in Blackness. Thank you so much, Dr. French, for being with us today. Before doing the evaluation everyone, can you unmute yourselves and give a shout out and thank you to our presenter and to our ASL interpreters?

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

Take just two minutes for an introduction to Howard French’s work, in his own words.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

|

Congo, Coltan, and Cell Phones: A People’s History by Alison Kysia Lessons for How the Word Is Passed by Bill Bigelow, Jesse Hagopian, Cierra Kaler-Jones, Ana Rosado, and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Poetry of Defiance: How the Enslaved Resisted by Adam Sanchez Sun City – A Teaching Guide by Bill Bigelow Witness to Apartheid: A Teaching Guide by Bill Bigelow |

Books

| In addition to Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War, the following books were referenced. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa by Walter Rodney (Verso) How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America by Clint Smith (Little Brown and Company) Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers) Find more recommended books and resources for teaching about Africa at Social Justice Books. |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keyword(s).

|

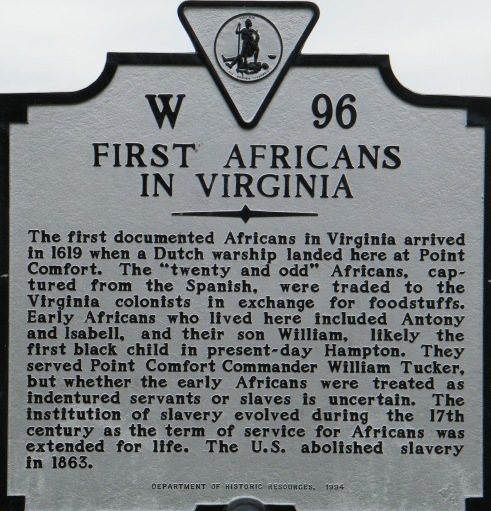

Aug. 20, 1619: Africans in Virginia April 7, 1712: Revolt by Enslaved Africans in New York June 6, 1730: Revolt on the Little George Jan. 1, 1804: Haitian Independence Jan. 8, 1811: Louisiana’s Heroic Slave Revolt Jan. 15, 1817: The Vote on Colonization of Free Blacks in West Africa July 2, 1839: The Amistad Mutiny March 17, 1856: Laws Enacted to Thwart Freedom-seekers on Ships Feb. 7, 1926: Carter G. Woodson Launched Negro History Week April 1, 1955: ANC Protest Bantu Education Act May 27, 1972: First African Liberation Day Demonstration on the National Mall Aug. 18, 1977: Steve Biko Arrested Feb. 11, 1990: Mandela Released from Prison |

Participant Reflections

With more than 250 attendees present, the conversation and chat were lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The history I never learned about Africa.

A completely new understanding about how Europeans exploited Africa, starting with the Portuguese’s Elmina, and how they created chattel slavery — a new arrangement in human history based solely on race. Without the gold the Portuguese mined, they never would have been able to build ships to make their way to the Americas, and Columbus’ “exploration” would not have been funded by the Spanish.

The most important things I learned were the role Africans played in creating the early global economy and helping to explain their role in making the New World colonies so valuable, thus creating the foundation for European power (i.e. they didn’t do it on their own!).

Africa was the birthplace of modern civilization — not just human beings.

The role of consumption/cash crops can be traced back to Mansa Musa and other African explorers. This is something I’ll continue to sit with, and I can see a clear connection to capitalism that makes me want to dig deeper.

I could have listened to Howard French for hours and hours, and his rebuttal to the argument that “slavery has always existed.” But beyond that, how he used plain and simple language to show the direct line of African genius, how it played out and was capitalized upon in the culture of Europe, giving birth to the modern idea of democracy.

How Africa and Africans are the bedrock of American culture.

His clear explanation of how and why the enslavement of Africans was different from the enslavement that had always existed, throughout history, in every culture and society. It was based on dehumanization (chattel/cattle) and it was based on race. Of course, it was also the economic driver of this country (as he also clearly noted). Leon Litwack and others have noted that, on the eve of the Civil War, the worth of enslaved Black folks was equal to the worth of railroads, banks and factories combined!

Centering Africa in the narrative of exploration and wealth-building of the West.

I learned new, more nuanced connections between world history and U.S. history topics that center the narrative on Black history.

The distinction between chattel slavery and other forms of slavery and why that difference is so important to understanding U.S. history.

I am grateful for a source that connects so many dots related to the legacy of chattel slavery.

Chattel slavery “deprived the enslaved of their social existence” and this concept helps me understand why the enslaved Africans would risk their lives to escape to freedom.

What will you do with what you learned?

I hope to not only center Africa more in my own American history courses, but also, as the incoming Dean of my school’s history department, bring these lessons into the world history curriculum, as well. Our students call out for more diverse curricula. Centering Africa, as our discussions tonight did, does that better than any token inclusion of diverse voices (although that, too, is important).

Making more loops back to African legends and also “ordinary” stories of people reflecting historically significant moments. Storytelling is a really powerful tool to teach history.

I had read Howard French’s book in the summer and used it as a source to guide instruction in our pre-colonial Africa unit. So, much of his coverage of Africa as the driver of world history was familiar to me. I’m going to incorporate some of the things he had to say about chattel slavery as we look at roots of anti-Black racism and the Transatlantic slave trade in a couple of weeks. The framework that I used before, that I’ll revisit, is Myth v. Reality. Students want to know the truth and I’m so amazed how ready they are to question Eurocentric narratives around the history they’ve learned in school so far.

I will be teaching the AP African American Studies pilot next school year. I would love to pose questions based on the book. For example, which word more clearly defines the places where Africans were enslaved — prison industrial complex or plantation?

This was hard for me as a Kindergarten teacher to place in our study, but I do think that working with the 1619 Project book for children is a start, maybe exploring the science that African people developed that the Europeans took and made their own to create this society.

I am a volunteer instructor in after-school programs and Saturday schools in Seattle and will definitely expose current and future students to this knowledge.

The discussion of Elmina provides an important segue from Mansa Musa and Mali, which we cover in the 8th grade, and the early modern empires, which we take up in the 9th grade.

Using primary documents and sources to show the economic impact, social legacy, and foundation of wealth for the West. Speaking it, showing it, and connecting the legacy.

I really think this helps me continue to refocus my world history curriculum on Africa and constantly ask my white Anglo-Saxon self, “Am I leaving Africa out of this narrative that I am teaching?”

In the breakout room there was a sister who runs a Saturday and after-school program that teaches this history. I am re-inspired to do that in my community.

I lead Southern civil rights tours and I will use some of the content to give context to what we are seeing.

I’ve ordered the book and will read it. I also want to begin to incorporate “prison industrial complex” into my vocabulary instead of “plantation,” for accuracy.

I will bring what I have learned tonight to teaching preservice teachers in my courses in the fall semester.

As a teacher of both world history and Ethnic Studies, I will use today’s lesson as well as Howard French’s book to center and uplift Blackness, and continue to tell the story of imperialism and colonialism.

Continue to learn and strive to remove the blinders in society, because the whitewash is real here in a world of systemic racism.

Use it to challenge our curriculum audits and to develop policies to ensure this information is being taught to children.

I will infuse it into everything I teach from an anti-racist perspective. There is no anti-racist education with this foundation of historical, truthful African-centered perspective.

Presenters

Howard W. French is a career foreign correspondent and global affairs writer and the author of five books. He worked as a French-English translator in Abidjan, Ivory Coast in the early 1980s, and taught English literature for several years at the University of Abidjan. He joined The New York Times in 1986, and worked as a metropolitan reporter with the newspaper for three years, and then from 1990 to 2008 reported overseas for The Times as bureau chief for Central America and the Caribbean, West and Central Africa, Japan and the Koreas, and China, based in Shanghai.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the staff of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn