On September 12, the Zinn Education Project hosted historian and author Alaina Roberts in conversation with social justice educator Cierra Kaler-Jones about the Reconstruction era connections between Black freedom and Native American citizenship in the context of westward expansion onto Native land. This class was part of our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle series.

There was a packed (virtual) house, with participants joining in with reflective and timely questions. Here are a few reactions from participants:

So many that it’s hard to think of just one. Several: 1. That there were Indian freedpeople in Tulsa during the massacre, 2. that Native freedpeople saw themselves as just that — not as Black freedpeople — and felt tied to the Native land on which they’d lived (and been enslaved), 3. that all those Black towns (like Boley) in OK were a result of the govt. giving Native land from the Creek Nation to freed Black folks during Reconstruction. . . until (of course) they then took it back, established OK and put it under Jim Crow laws.

I am adding a search of the Dawes Commission Records to the primary resources I use to teach Reconstruction. I am working diligently to show my students that the failure of Reconstruction was not the fault of the freedmen but the failure of the U.S. government to ensure and safeguard the political and economic gains of freedmen.

Hearing about some of the intersections of identity and politics, war and peace, between white, Native and Black Americans was riveting. There was so much more to consider than what is readily available in public school textbooks in the U.S.

This is going to influence how I introduce colonial America to my 4th and 5th graders.

The format was excellent. I really appreciate the skillfulness in facilitation, the length of the session, and the fact that breakout rooms were placed in the middle. It was perfect!

The Zinn Education Project always exposes me to history that I never learned, which sets this background for me to be able to integrate it into what I’m already doing in the classroom.

Event Recording

Transcript

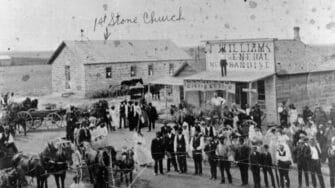

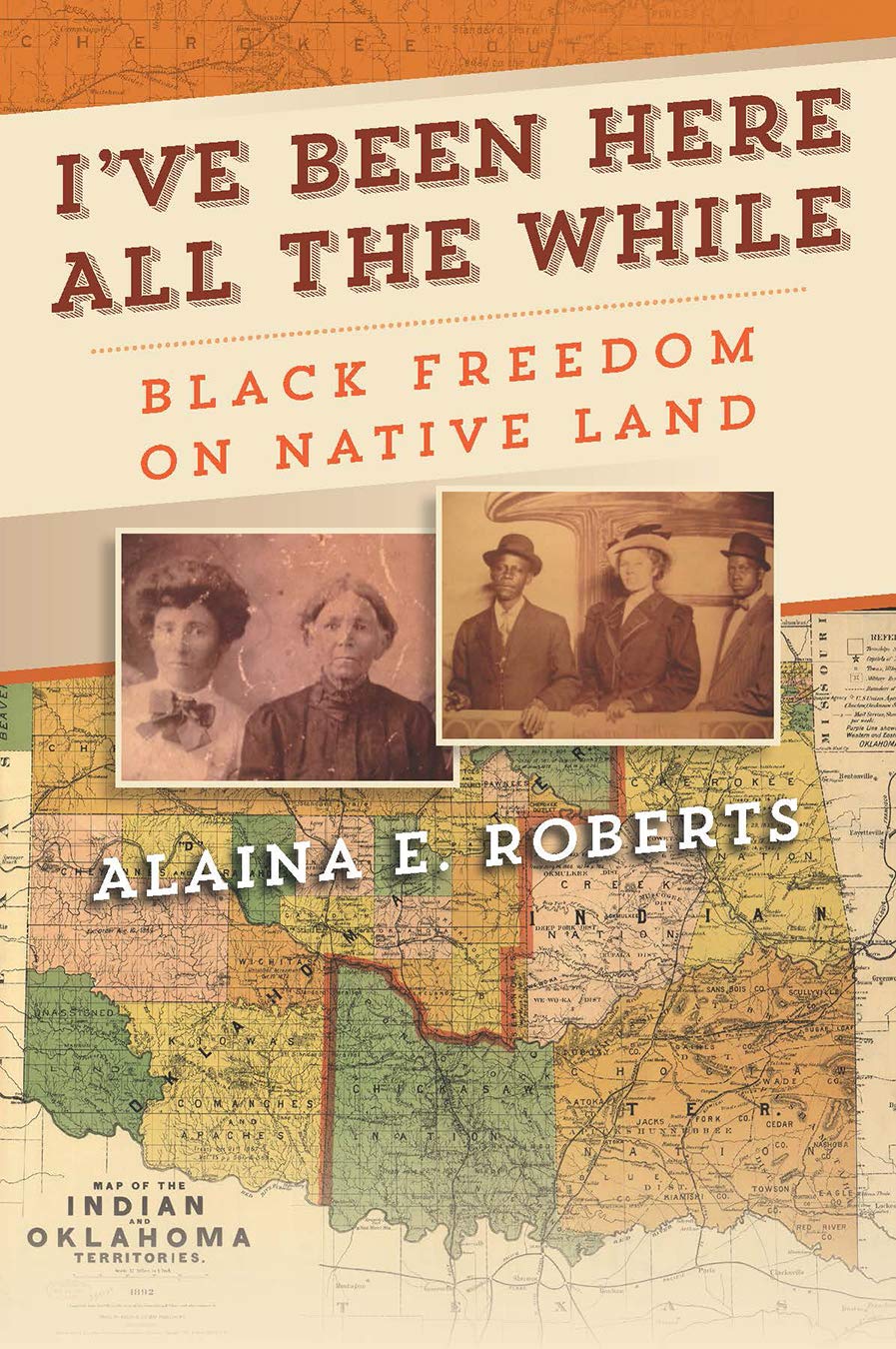

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion. Cierra Kaler-Jones: On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everyone to our class with Alaina E. Roberts about Black freedom on native land. As Deborah shared, I’m Cierra Kaler-Jones. My comrade Jesse Hagopian couldn’t make it with us tonight, but he is so excited about this conversation and looks forward to ways that we can continue the dialogue. Some of you are joining for the first time — I saw about 50% — and some have participated since we launched this series. So it’s truly a gift to be able to share this time together, and I thank you for being in virtual community with us. I know you all are holding so much in your personal lives, in your work, so solidarity to the educators who are striking in places like Columbus and Seattle, and solidarity with all of the educators who are joining us tonight and continue to teach truth in light of legislation, and in light of attacks that are trying to deny us and bar us from teaching the critical history that we need in order to know ourselves in the present, and to be able to dream new futures together. And so today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change. We’re hosting this session today as part of our Teaching for Black Lives Campaign and Teach the Black Freedom Struggle course series. We offer free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used — I use them all the time for middle and high school classrooms — from the Zinn Education Project website. Today’s ASL interpretation is provided by Krystal Butler and Tyriibah Royal-Lampkins, so please add ASL after your name in brackets for the breakout room placement with an interpreter. Before we begin our conversation, we want to find out who is in the room and go through our plans for our time together. We are going to post a quick poll to find out how many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, everybody is pulling up and others who are in the room with us. And many of you are in multiple roles, so please just pick your primary one. As we fill out this poll here, we also have members from our Teaching for Black Lives Study Group. So welcome. If you are in one of those groups, please add T4BL after your name. And it looks like the poll has ended. Here we go, the poll is sharing. It looks like 52% are K through 12 teachers — welcome, welcome. So grateful for you all and the work that you move every day. We have 3% K through 12 students — shout out to the students that are pulling up to the room. Three percent family members to students — thank you loved ones for showing up. Eleven percent teacher educators, 6% historians, 3% librarians, and 23% others. So, if you are putting yourself in the other category, go ahead and drop in the chat, everyone introduce yourself. We really want to hear from you in this virtual space. Speaking of the chat: throughout the session we want you to use the chat box, post your questions, your comments, resources, and ideas. We’ll do a short evaluation at the end. And then in about a week we will share the full recording from the session and all the resources shared in the chat box. Please also tweet what you are learning so we can retweet and lift it up. After about 25 minutes, we will pause so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups to share your thoughts with one another. And with that, I am so, so, so excited. Please join me in welcoming Dr. Alaina E. Roberts. Alaina Roberts is the author of I’ve Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land, and is an award winning historian who studies the intersection of Black and Native American life from the Civil War to the modern day. She is an assistant professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh, and y’all if you do not have this book, I’m telling you, this history shook me. I did not learn any of this in school and I cannot wait to collaborate with all of the educators on this call about ways that we could bring this into our classrooms. Especially now in this moment, this history is so critically important. So, thank you so much Dr. Roberts for your work, for being with us, for sharing your expertise, and sharing all you’ve learned. I’m so looking forward to the conversation tonight and to learn with and from you. Alaina Roberts: I’m so happy to be here. Thank you everyone for coming this evening. Cierra Kaler-Jones: We will dive right in with our first question, all about Reconstruction in the West. So, your book takes an expansive view of Reconstruction, going beyond the South and beyond narratives that Reconstruction was mostly about African Americans gaining political rights. You write about Indian Territory in present day Oklahoma, and as you say in your book, “as a space where a different sort of Reconstruction project occurred, that involved the successful pursuit of land.” So to start, could you talk a little about why the history of Reconstruction in the West is so important, and what gets lost when we treat it as peripheral, or when we don’t learn about it at all? Alaina Roberts: My research and my teaching are really connected. Right now at the University of Pittsburgh, I’m actually teaching a class that I’ve called the Black West. The basic premise of that class is that Black history doesn’t just happen in the South, and it doesn’t just happen on large cotton plantations. And so that is also really kind of the theme of my book — that there are all these different kinds of stories and histories and narratives and experiences that people of African descent have in North America that we don’t learn about, because we learn this one narrow narrative that doesn’t actually encompass all of these things that people went through. And so for my book, specifically, I focus on Black people who were owned as slaves by Native Americans. Those Native Americans are from five Indian nations. The Chickasaw and Choctaw nations — where my own ancestors were enslaved — the Cherokee, Seminole, and Creek nations as well. So when those nations were forced out of their homes by white settlers and the American government in the 1820s and 1830s, they and their slaves embarked on the Trail of Tears. First of all, the Trail of Tears is both Black and Native history in my book. And these people then arrive in Indian Territory, which is, as you said, now the state of Oklahoma. So it wasn’t white settlers who introduced Black slavery to this part of the West, it was these Native American slaveholders. That’s where my book really picks up, helping us understand this Native American and Black removal and resettlement, and then putting this in the idea that if we have slavery here, then we also have a Reconstruction project when slavery in these Indian nations ends. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Thank you so much for that. And I appreciate you naming that this is also Black history. As we think about the larger course content around Teach the Black Freedom Struggle that this is part of the longer Black Freedom Struggle. I also want to name for everyone in the room that an excerpt from your book actually appears in the Oklahoma vignette of the Zinn Education Project Reconstruction report. So please, please, please check out that report. It shows that schools woefully do not teach the truth and the expansiveness about Reconstruction. And this is just another reason why your work is so critically important to that history. You talk about the five tribes. In making a connection in the first chapter, you talk about how enslavement was rooted in the culture of the West long before the lead up to the U.S. Civil War. So, what should people know about enslavement and emancipation and the five tribes, and how do they intersect with enslavement and emancipation in the United States? Alaina Roberts: There are definitely important similarities and differences. I think the most important similarity to remember is that there is no one kind of experience of enslavement in the United States or in any of these Indian nations. And so when I look at the sources, I see, of course, enslaved people talking about horrifically cruel owners who enjoy sadistic torture, who enjoy beating, whipping, raping, etc. But there are also enslaved people who say my own are viewed it as a labor system, and they were kind to me. And this is, of course, not to excuse slavery, but to just kind of emphasize that enslaved people are aware of what’s going on in different plantations. Their experiences are relative to what they know occurs in other places. And so we should take seriously, I think, the way they personally feel about what they’re going through. But for the interesting similarities, there are also similar laws in all of these Indian nations that we think of as only in the United States. So, the same laws that regulate the assembly of people, stopping them from gathering in large groups, laws that stop them from learning to read or write, those same laws are present in all of these Indian nations. Because there is the same fear of rebellion, there’s the same fear of an educated workforce that might be angry and then try to overthrow the system. But one of the important differences is that in Indian nations, Black men and women have the opportunity to serve as what the historians would call cultural intermediaries. And so they speak English and many of their owners do not. They have been previously exposed to Christianity and many of their slaveholders have not. And so they serve as translators, as proselytizers, and for this reason, they’re present at important meetings about trade and politics. Sometimes this leads to their freedom, sometimes it doesn’t. But it does, I think, give us a different feeling of inclusion — almost like in these societies that they have these important roles that they often are not able to fulfill or hold in the United States. But of course, no matter what you’re able to do in either space, you are dehumanized because you are not legally a person. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Thank you. You talked a little bit earlier about how this history comes very much from your own history. And so the story that you tell in this book comes not just from your expertise as a historian but also your perspective as a descendant of all four peoples in this narrative — Indian freedpeople, African Americans in the United States, Native members of tribal nations, and white settlers. So it’s really incredible to see the insights and the stories from your family and the way that you weave those in. Could you talk a little bit more about your definitions for each of those groups? And what was it like to research and write this history? Alaina Roberts: As you mentioned, there are the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indian people who I specifically follow, but I’m looking at all of these slave-holding nations — there are white settlers, there are African American settlers, and then there are what I call Indian freedpeople. I make this important distinction between the groups of Black people that I follow in this book because I’m trying to really get my reader to understand that everyone is not an African American in this period of time. People like my ancestors who live in the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indian nations, that is their nationality. They live in a nation that is sovereign, that is not considered part of the United States. And so when they think about themselves and their identities, they’re not thinking of themselves as American or African American. I think that’s an important differentiation between the struggle of African Americans and their desires to become American. And so this kind of melds together when we get into the 1900s. But before that, we do have these kinds of different groups. When I was in college I went to school at UC Santa Barbara and I was really trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. What all of us go through. I knew I loved history, I knew I loved writing. And I was talking to my dad about a class I was taking: We had an assignment to do a family tree. So I really started looking into some of this history that I knew some of the older people in my family had, but that I hadn’t previously been interested in. One of the first documents I found was of my great great grandmother, which I’ll talk about later. But it was amazing to really see this completely different story about Black identity and about mixed race identity that was not part of the African American historical narrative. And once I learned about it, I saw that it was not present in other things like documentaries, like other books, about, supposedly, this all-encompassing Black experience. That really made me want to write a book that shows that we can think about the importance of the Black Freedom Struggle and how long it’s really been present in North America, but also the diversity within that struggle and what it means that different people want different things at different times and in different places. Cierra Kaler-Jones: I appreciate that so much. And it’s making me think about history overall: How history is all around us, and history is within us. Throughout the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle course series, we’ve also heard from scholars like Clint Smith and Martha Jones, and how they use their lineage and their own histories as a grounding or a foundation to explore the larger Black Freedom Struggle. So, I’m just appreciating the work that you do, and also the larger connections that I just continue to see and thinking about all of the educators who are on this call that might teach oral histories in their own classrooms as a space for young people, for students, to be able to see their stories and their ancestry as history as well alongside the information that they learn in school. Speaking more about stories and narrative, and moving more into some of the Reconstruction work, most narratives really look at Reconstruction from the 1860s to 1877, ending with the removal of the last U.S. troops from the South. But we know that it’s not that simple, and that understanding Reconstruction really requires a longer lens like you share with us. You wrote about the 1860s to 1907 as a sort of prolonged Reconstruction Era in Indian territory. One thing that you also talk about is the Dawes Commission and how it played a major role in the land allocation process and its record holds powerful testimonies, including testimony from your great great grandmother, Josie Jackson. So, could you talk more about this prolonged Reconstruction time frame in Indian Territory and the Dawes Rolls? I would love to just hear more about how you use Dawes Commission records to draw out some of those voices and stories of Indian freedpeople who cultivated community while grappling with settler colonialism in this period. Alaina Roberts: Well, listening to the introduction, it sounds like we have a very well-read audience. So it was probably not a surprise to many of you that there is still a lot of debate among historians about what Reconstruction is, when it ends, when it begins, who was involved. I am part of a group of scholars who is really trying to push the discipline, to look at the West as a space where there is a different kind of project going on, one that is still going on, related to slavery, emancipation, as well as Native American history. So, I’m going to give you my spiel and hopefully persuade you that Reconstruction is important to, really, the entire nation. If we think of Reconstruction very broadly as a time period in which the federal government is attempting to rebuild physically — like infrastructure, building railroads — but also politically and trying to really change the nation to encompass new Black citizenry. All of these things are also happening in the West through the federal government. Quickly, I need to back up and say that the five slaveholding Indian nations I mentioned all fight in the Civil War on two different sides. Just like in the United States, there are families split, there are nations split, people fighting for the United States, people fighting for the Confederacy. They’re fighting for multiple reasons: to protect their land, to get better treatment from the U.S., to protect the institution of slavery. After the war, when different branches of the federal government are deciding on how former white Confederates will be punished or not punished, the same decisions are being made about these Native American Confederates. What the Secretary of Interior at the time really decides is that he’s going to punish these slaveholding Indian nations. He’s going to use the fact that they fought for the Confederacy against them, essentially, as leverage. There are about 14 battles actually fought in Indian Territory — this is not just a small thing, it really is actually involved in the war — and this destroys people’s homes, businesses, and communities. These Indian nations desperately need help from the United States and the money that they’re supposed to be getting from the United States. So they’re able to say, “We want you to sign new treaties after the war, or we’re not going to give you all the things that we owe you already.” And so these treaties in 1866 do all of these things that we think of Reconstruction doing in the United States. It forces these Indian nations to allow railroads to run through their nations — there’s your infrastructure. It says that these nations have to free their slaves — give them citizenship in their nations and also give them free land. When I mentioned my family and the sources that I found, those sources are all tied to land and the fact that they really wanted to not just obtain that land, but also maintain that land and their presence on that land. All these sorts of markers of Reconstruction are present in these Indian nations. So when the Indian Territory eventually becomes Oklahoma, it’s because the federal government wants to really subsume this western space into the United States. This process of land selling: So first, the land is given up in these treaties, hundreds of thousands of acres of land that was supposed to always be Indian nations’. Then that land is supposed to be allotted to every Native person and every freed slave in those nations. And then there will be surplus land, conveniently, that can be lived on and settled on by white Americans. Walking you through all these things, the legislation that results in the sale of this land is the Dawes Act, which you mentioned, and then the Curtis Act. So the Dawes legislation says that these five slave owning tribes have to determine who all these people who are supposed to get this land are. Who are all these Native people who are members of this tribe? Who are all these former slaves who were owned in these tribes? In order to do this, they create rolls, [and] those rolls are called the Dawes Rolls. And there are two different rolls. So there is the Blood Roll, which is Native Americans by blood, by ancestry, and then there is the Freedmen Roll. The Freedmen Roll is the roll of enslaved people and their children. The Dawes Commission is put together to determine who are the rightful claimants to this land. Because there are plenty of people who come in after the war and try to get onto these rolls because they see there’s land being given out. So there is a need for someone to really kind of arbitrate this process. But there are so many issues with this process, a predominant one being the fact that there are many Black people who have Native American ancestry. And most of those people do not end up on the Blood Roll, the Native American Roll, for various reasons — a lot of them having to do with racism and the idea that Native people are mixed race people only look a certain way. But the rolls themselves, as well as the process through which people get themselves on the rolls, is where I really have the richest sources. When you apply to get your land and be on this roll, you submit your name, your age, the community you live in, your relatives, like your children, your husband, you might have people come speak on your behalf, and you yourself might be called to testify. And that is the record of my own family that I found. My great great grandmother, Josie Jackson, I found her in front of this commission, telling them essentially why it’s important for her to get this land, why she wants to stay in this community, even though she’s actually living in Dallas, Texas, which is hundreds of miles away from Ardmore, Oklahoma, where we still have that land. And yet she makes this journey back and forth constantly to see her family and to really maintain this connection to this space at a time when travel is very scary, especially for a woman. And so to me, that really kind of told me that the core of my book, and of my story, was land, and what land meant to them, to my family members, but also to other groups within this time period. Because land was capital, but also land was identity. Land was community and land was all these different sorts of things. So this process really gives us the ideas that not just Black people, but also Native people, have about where they live, where they want to live, and really the realization of Reconstruction’s promise and how someone got land, someone got their 40 acres — it just wasn’t African Americans in the United States. Cierra Kaler-Jones: There are so many different directions that we could go in for the next question, but I want to speak on the belonging first. Then I think we’ll move to reparations after that, because you left us on such a good closing sentence on that. Belonging is something that fascinates me so much, and I really just was drawn to your particular definition of it, and how you talked about how folks did not always seek citizenship, but rather they clung to kinship networks and natal communities, like you were talking about your great great grandmother going back and forth. You note that the book’s title, I’ve Been Here All the While, represents in your words, “both words spoken verbatim by numerous Indian freedpeople as a means to denote their long held connections to Indian Territory, and the sentiment that each wave of settlers in the West took on.” So, can you tell us more about the significance of that phrase, “I’ve been here all the while,” and how Reconstruction’s promise tied into these ideas of belonging and citizenship and land within Indian nations and the United States? Alaina Roberts: When I mentioned my ancestor, Josie Jackson’s testimony, that is essentially what she was saying — that I have grown up on this land, in this community, and this is where I want to stay. But there were numerous Indian freedpeople, these former slaves of Native people, who use those exact words, “I’ve been here all the while. I have lived on this land.” Some of them even talk about coming over on the Trail of Tears with their owners, really kind of driving home the importance of membership in that nation. But also how that new land is their home, just as we would think of it as Native American’s new home. This was kind of mind-blowing to me, because we don’t think of land usually, I think, as being as important to African Americans or people of African descent as political rights. And so yes, of course, voting is so important, people died for that. But there is this other story — because these people actually have access to land and the ability to obtain that — where land is kind of their main focus and really the key part of their identity. So making my book’s title I’ve Been Here All the While is me really saying I’m trying to speak for these people and say that land was important to them. This land, for most of these nations, is tied to citizenship. But actually for my family members, they never had citizenship and so they were living in a nation in which they did not have any rights after a certain period of time, where there was a certain threat of violence. And still, because they had that land, it was so important to them to stay in that space instead of journeying out into the United States when they could. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Wow, thank you so much. This history is just really mind-blowing, and there’s so much complexity and so much nuance that I think that you hold with so much care in both your writing and in the ways that you’re expressing with us today. As we talk about land, what you write in your book in terms of thinking about reparations, you write, “in the process, Indian freedpeople became the only people of African descent in the world to receive what might be viewed as reparations for their enslavement on a larger scale.” Can you talk more about that, and what the implications are for today? What does it mean for reparations today, especially when reparations, in this case, were built on violence and forced removal and seizure of Native land? Alaina Roberts: I think there are multiple parts of reparations — at least two, maybe more. We usually think of it as there is kind of an apology, there is acknowledgement that a wrong was done, committed by the representative of the nation, or the group who did the wrongdoing. And then we also have some sort of land, or monetary gift, or whatever you want to think about the commodity that is given to the people in exchange for their sorrows and what they’ve suffered. The 40 acres is there for people like my family, the land is there, but it’s not given by the Native American nations, per se. It’s given by the federal government, who is really looking at people of African descent in these Indian nations and saying, “Okay, we hear all this discussion in the United States about land, about the Freedmen’s Bureau, about what could possibly be done to help African Americans be self-sufficient. That’s not happening in the United States. But we can do it over here in Indian Territory, we can get these people land. And that’s because we’re taking it from Native Americans, we’re not taking it from white Americans in Indian Territory.” So that makes it okay to these white men making these decisions. They’re doing this not necessarily out of the goodness of their hearts, but they are doing it pointedly to provide a foundation, an economic foundation, for these Black people. And it does. I mean, there is an economist who’s done the work to show that Cherokee freedmen and Cherokee freedwomen actually do have more upward mobility, more education, a better sense of community, because of this land. But of course, it is also part of this greater Native American dispossession — they’re giving them land that isn’t really theirs to give, and also kind of solidifying this antagonism between Black and Native people. That, for me, makes it, I think, clearly reparations in the sense that these white Americans think that that’s what they’re doing. And economically, that does make a difference. But on the other hand, the Native American nations who actually did the slaveholding are not themselves acknowledging any sort of wrong. If you look today at what is happening with Native nations and the descendants of these former slaves, often there is still no acknowledgement. There is still discrimination. There is still very much a need for that kind of reconciliation. Now, as far as what it means for greater reparations in the United States or across the world, I think it is a clear example that reparations can work, and that at least in the 1890s, it could help a Black family because they were starting from nothing, literally. Now, there are so many decades upon decades of discrimination and ways that things like redlining have hurt African Americans and people of African descent that it’s just so many more layers to strip away. But I don’t think that that means that we shouldn’t try, and we shouldn’t think through these ideas. It’s just that I don’t think we should be able to say it’s never happened because it has — someone thought that it was doable and took the time to really think it through and use it as almost an experiment on a group of people. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Thank you. I appreciate you breaking that down for us so much. As a bit of a shameless plug, the Zinn Education Project — for everyone that’s on the call — has a lesson where students actually design a reparations bill. So I think that this content, this history that you’re sharing with us, would be such a critical exploration with students, alongside that lesson of what does it mean to have this conversation about reparations? And how do we ask these critical questions about whose land and who are the original stewards of this land as part of those conversations. So I appreciate you bringing that into the space. One of the things that you also named was the tensions between Native and Black folks. In a chapter in your book you write about the complexity of these interactions on Indian Territory between African Americans who’d moved from the South and Indian freedpeople, and you discuss the town of Boley and the Creek Nation as a prime example. How does the history of this particular town, in present-day Oklahoma even, illustrate or further illustrate this complexity? Alaina Roberts: Well, so Boley, Oklahoma is, I think, one of the most well known all-Black towns of Oklahoma. If you didn’t know, Oklahoma is the state with the largest historical all-Black towns, which means that through the 1800s and early 1900s, there were hundreds of thousands of African Americans going to these spaces, beginning their own communities. Because there are already Black people here, these former slaves of Native Americans who are getting land, Indian Territory becomes a huge draw for African Americans from the United States. Because they have been disappointed by the lack of help from Republicans in at least the economic foundations of creating a new life after emancipation, they’re looking, really, for places that are not just the potential to begin anew economically, but also a place to be free from white violence. A place where they can create a store that’s successful without a white neighbor coming by with a gun. So Indian Territory looks to them to be a possible paradise; a place where there aren’t many white Americans yet. Especially none with power. Because it is really an Indian-run space, there is really an opportunity that isn’t there in the United States. Because these Black people within these Native nations are citizens, they’re able to vote, they’re able to serve on juries, they have all of these things going on through the 1890s and into the early 1900s that, for most Black people in the South, is no longer possible — at least on a larger scale — because of the huge rise in Jim Crow violence. So, when African Americans come to Indian Territory, and the region outside of it, they create towns, sometimes making alliances with Indian freedpeople, with these former slaves and Native Americans. So Boley is an example of that, because it originally started the allotment of the land given to a Creek freedgirl by the Dawes Commission. And then it comes as really a place where speculators are growing people. So African Americans come from the states, they create schools, businesses, social organizations, Booker T. Washington visits the city and says it’s an example of what Black ingenuity can create. It really becomes well known as a place that is the epitome of Black excellence. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Thank you. As we’re talking about Oklahoma: Oklahoma, I think, is of particular interest for many different reasons. As we bring it to present-day, a teacher was just fired for sharing a QR code to the Brooklyn Library banned books [list]. You refer to Oklahoma, of course, a lot in the book, and Oklahoma land claims from whites, Indians, and people of African descent over many waves of migration. You call it a powder keg that exploded in 1921, with the Tulsa race massacre. This was one of the single worst incidents of racial violence in U.S. history and a direct attack on Black wealth, on Black Wall Street. And Oklahoma didn’t incorporate the Tulsa race massacre into statewide school curriculum until 99 years later, as recent as 2020. We think about all of the newspaper articles and all of the archives that were essentially put away until recently, and we see this continued thread of the erasure of critical history. So, can you talk a little bit more about the importance of students learning this history, in light of our discussion today or in the broader history of the United States? And as we talk about that, I would love to invite folks if you have questions for Dr. Roberts, we’re going to go into breakout rooms after we talk about this topic. But please put your questions in the chat box so that we can curate them and we’ll come back after our breakout rooms with more discussion and dialogue. But yes, can you talk a little bit more about the importance of students learning this history? Alaina Roberts: Tulsa’s Black Wall Street is another space where Indian freedpeople mixed with African Americans. You have these original land allotments that become communities, where you have these different groups of Black people coming together, working together. But it also is so emblematic of the change that happens once you take Indian Territory from a Native American space to a white American space. The Secretary of Interior, and the federal government through him, goes through all this trouble to ensure that Indian freedpeople have land allotments, have rights, have membership in Indian nations, only for the federal government to then try to completely dismantle tribal nations, and then, really, declare that Indian Territories were going to become the new state of Oklahoma. And the state of Oklahoma, as you said, introduces Jim Crow legislation that completely changes the lives of Indian freedpeople, as well as these other African Americans who come to join them. And then life is more similar to what they had tried to escape in the South. They do still have land and businesses that they created before statehood. They continue building on that, becoming even more successful. And now with the hundreds of thousands of white Americans who had come to settle in Oklahoma, they have to deal with the jealousy, with the anger. And in 1921, the Tulsa massacre then really becomes this kind of ultimate expression, I say in the book, to show that white supremacy is now the law of the land. Even though this place was formally under native governance, even though formally the federal government was ensuring that there was a measure of Black rights in this space, when white Americans have claimed it, it changes. Now the United States is really only protecting white settlers. It’s, of course, a huge travesty that Oklahoma students didn’t learn about the Tulsa massacre for so long. But in my biased opinion, it’s even more devastating that they didn’t learn the deeper history behind the region, because they need to know why are Indian nations, like the Cherokees, even in Oklahoma in the first place? Why were all these Black people coming to Oklahoma and Indian Territory? All students need to learn about Native American dispossession, the way slavery was so important to the U.S. that they would encourage another group of people, Native Americans, to begin practicing it. Then, of course, that racial violence across the country disrupted the lives of African Americans and also Native Americans. So, this story I tell in my book, and how it connects to the Tulsa massacre, is really a larger story of how people of color relate to one another and interact. And I think a lot of that has also been censored in American history, because looking at the way people have worked together and also been torn apart by white supremacy is important to not allowing us to work together in the present. Cierra Kaler-Jones: I know we have to go into breakout rooms now, but when we come back, one of the things that I definitely want to talk about is solidarity. I’m looking forward to diving into that a little bit more. And I’d love to just point everybody to the chat — there’s so many great questions moving and questions that need answers. I just have so many ideas and so many thoughts for how I can teach the Tulsa race massacre more expansively now because of what you’ve offered in these critical questions that you’re bringing. So thank you, thank you, thank you. Dr. Roberts, in the chat box, Roberta had asked what is the legacy of this history for the present day relationships between First Nations and African descended peoples? To also fold in my own question as part of that, too, can you share with us some of the stories of Black and Indigenous solidarity that have happened throughout history, and even through present day, as Roberta’s question gets at. Alaina Roberts: There are so many different times and spaces where Black and Native people were laboring together, working together, intermarrying. If we look at the very first interactions when people of African descent were first in North America, they came with the Spanish. A lot of them met Native people along with the same explorers who were killing Native people and taking their land. So, they were antagonists, but they also intermarried and related on different levels. During the colonial period, you have Black and Native people working as slaves and servants on the same plantations running away together, forming communities that we might call maroon communities. And it’s really when you get into the 1800s that you see more differentiated experiences where Native people have to really decide where do we want to be in this racial hierarchy. Because Native Americans are looked at as different from people of African descent. Native people are looked at by founding fathers like Thomas Jefferson and George Washington as changeable, as people who can be assimilated, who could be converted to Christianity, versus Africans and African Americans who cannot be — conveniently, of course, because they’re needed for labor. It’s really up to Native people, individually but also as tribal nations, to determine what their relationships with African Americans are going to be. And unfortunately, most of them choose the path of least resistance, which is to accept that now these people are seen as inferior. By going into the 20th century with the Civil Rights Movement, with the Black Power movement, you also see what’s called a Red Power movement — Native nations and Native people working for their own version of civil rights, which is not necessarily inclusion in the United States, but more so a recognition of tribal sovereignty and their differences with African Americans and other people of color. In thinking about the relationships between Black and Native people, historically and today, we do need to remember that there are important differences. Native people have their own tribal nations, but there is very much a similarity between what they’re fighting for, against general prejudice, against discrimination, and the idea that they are in some lower tier of humanity. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Thank you for sharing those stories. We know that when we ban history, [when] we ban teaching the full history, one of the biggest parts that we ban is teaching those stories of solidarity that allows us to see ourselves in community with one another as a force for social change. It’s always been everyday people that have banded together in service of change. But you also talk about some of the challenges. And in relation to some of the challenges in the chat, Joanna Kenty had asked the group, “Of the five civilized tribes that you mentioned, was enslaving a part of assimilation, or was it more widespread, among other tribes, other nations?” Alaina Roberts: The participation that we see within these five tribes in the system of slavery is definitely a part of why they are seen as more assimilated, more civilized, than other Native people. They are really the only five Indian nations that were looked at as being involved in chattel slavery, the same model as white Americans. There are other western Indian people, like the Comanches, who have Black people in their nations as kind of a servant class, but it’s not permanent in the same way that it is in the United States and in these five nations. These people are also not seen as not human, they’re just seen as a source of labor — something to be traded, something to be bought, something to use to get something from white Americans. It’s a different way of thinking that the five tribes allow to really grow within their nations and it is part of their larger change to adopting things like a similar government structure to the United States. Still to this day, these five nations have a judicial branch, an executive branch, and a legislative branch, just like the United States. They had newspapers. They had tribal leaders who were getting educated in the United States, and so they were very interested in assimilating to a certain degree that allowed them to be viewed as different and allowed them to gain enough education and knowledge about the United States. They were able to bargain on almost a different plane than a lot of other Native people. Cierra Kaler-Jones: As we talk about the five tribes, Bill Bigelow had asked, “Was there an abolition movement within these tribes?” Alaina Roberts: There was. All of these tribes — just like the United States, there’s not one Native American experience or Native person and identity within these tribes — they are divided on many different issues. Slavery is certainly one important issue that divides the nations. The Creek Nation actually split in two in the late 1700s over slavery and other issues, because slavery is considered assimilation to a white American way. And so Creeks and Seminols are really split on do we want our nation to go this way, are we interested in really changing ourselves to appeal to white Americans? The Seminols go off into Florida and are really not part of the same kind of development of slavery in these other nations until they are forced, through removal, to Oklahoma later on. When we think about abolition, I think we should think of it as in the United States, as a smaller group that has less power, but one that certainly represents a diversity of thought and identity in Native American nations. Cierra Kaler-Jones: As a follow up question, Elizabeth asks, “Was there resentment toward the five tribes like there was against whites in the South for enslavement?” Alaina Roberts: I wouldn’t say so, because it’s not seen as the primary reason that they fight in the Civil War. Land, and really kind of keeping their political identity, is more important. So, if I go into a little more detail with the beginning of the Civil War, the Confederacy is appealing to different countries, like France and Britain, for help in the war. And they also go to these other Native American nations and appeal to them, saying “We know that the United States doesn’t treat you the way that it should.” To the Cherokees they say, “We know that in your treaty you have the right to send a representative to Congress and the United States has never done that. We will do that for you” or to the Chickasaws and Choctaws, “We know the U.S. hasn’t paid you the money for your land and we’re going to do that.” They really have these ways of trying to persuade Native Americans to work with them, to ally with them, that aren’t even necessarily related to slavery, but more so to the political identity of these nations as partners that have not been treated as such by the United States. So, when we look at sources after the Civil War, it’s more just kind of anger at the United States really taking this war in which they didn’t actually give Native people much help at all, and then using it to their advantage more so. Cierra Kaler-Jones: There are so many great follow up questions. The good questions are just following up in the chat. This is so engaging. We have Ms. Judy Richardson with us, SNCC veteran, documentary filmmaker. Ms. Richardson asked, “As enslaved people with the five tribes, was there a way to end their enslavement, or was enslavement automatically passed down as it was in the United States?” Judy Richardson: In the way that it’s passed down automatically by the third generation, you’re just automatically enslaved. And I’m trying to figure out if you’re already on the plantation and second generation, third generation, there’s almost no way to get out of that unless you are allowed to buy your freedom. And even that is really slim. So I’m trying to figure out is there a way that it’s not automatic, that if you are on this plantation, your children and your children’s children will always be enslaved? Alaina Roberts: Definitely for the five tribes, yes. If I go into something that I really didn’t talk about in this discussion, before African chattel slavery Native peoples, like people across the world, were engaged in captivity practices where they would fight amongst themselves, go to war over territory, or because they didn’t like the other person, or resources. And they would take those people captive, and those people would not become permanent slaves; they could move up, they could marry into families, their children were not slaves. It’s really the difference between this prior form and racialized African chattel slavery. That is why I say it’s more like the United States, because they are abiding by this different rule that means that race is permanent, [and] slavery is permanent because it’s tied to race. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Thank you. I’m going to shift gears a little bit, because I know that this is something that you had mentioned wanting to talk about, and I certainly want to hear more about. And thank you to everyone for your thoughtful and intentional questions, and thank you, Dr. Roberts, for diving into those questions, too. I know that there’s, again, so much complexity and nuance in this topic. Moving into a little bit more about the storytelling piece with your family and your history, Nicole V in the chat asked, “Did you find the information of your ancestors via a public, searchable electronic database or [did] this information come from an actual archival research space?” Alaina Roberts: There is just so much information for people like me whose ancestors were enslaved in these Native American nations because of this Dawes process, because they really are gathering so much information on Native American nations and the people within them. Because of that, I can use ancestry.com, which now has all of these Dawes testimonies, all of the Dawes Rolls. Ancestry has also gotten a lot better with more general African American records. I think they have a lot of the pension records now which have Black soldiers in them. There are other records that you can find lists of online if you search ‘African American genealogical records.’ But yes, for me, I use Ancestry. I used other archives. Where people can go, the Oklahoma Historical Society has a reading room where anyone can go for free to look at the Dawes Roll. People will help you. But also other other things on microfilm, if you want to get microfilm, which is very frustrating sometimes. Certainly there is far more information out there for not just groups of people like me, but for African Americans who want to try to trace the ancestry that, for so long, many of us were not able to do. The communities now that are on ancestry, and on 23andme, are also really amazing for discovering people who you’re related to, you know, second, third, fourth, even more distant than that. And I’ve even gotten some help with my ancestry in the information gathering that I’m doing in my own family through that. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Wow. I have a follow up question, “I’d be interested to hear, was there a favorite story that you uncovered from your family?” Alaina Roberts: So, if you all out there read my book, then you will see that I have interviews with various people in my family throughout the book, most of whom have now passed on. It was so amazing to talk to my second cousin, Travis Roberts, who was in his 70s I think when I talked to him. He talked about how important it was for him to be recognized by the Choctaw Nation. There was someone else who mentioned that they read an article about what it’s like for descendants of these enslaved people in these current Indian nations and how it’s not so good, as I kind of mentioned. When you are a group of people, like my family — who, first of all, you’re not going to see your story of enslavement in a textbook, you’re not going to see it in a documentary about slavery— but you know it and you know that the nation did enslave you denies it and is able to get away with not mentioning it in museums and in its own history, you can really feel invisible, because people don’t know your story. The nation can ignore it. Whereas the United States can no longer ignore slavery because of African American activism. So, it really felt amazing to be able to just tell his story — like it’s in a book now, no one can deny that that is his identity. God, I’m tearing up because he never got that, and I just wish that I could give him that. But what I gave him, I think, was being able to write about it in my book. Cierra Kaler-Jones: No, that’s amazing. And thank you. I’m just moved that you have been able to hold your family’s stories in this way. And to be able to write it down and to pass it down so that it is physical, so that it doesn’t get erased — because that information is there for everyone to read. I’m so grateful and I’ve learned so, so much from you and from your family’s story. It’s very, very moving. I see lots of appreciation flowing for you in the chat box as well. I know that there are a couple of other questions, and I will invite again, folks, if you have more questions we have just a little bit of time. There is a question from Allison that says, “We have some history in North Carolina of Indigenous people being enslaved in the Caribbean. I’m curious to know if that history intersects with any of this history that we’re speaking of today, and what was the impact of exodusters and free Black folks moving to Oklahoma and Indian Territory on Native land ownership and resource distribution?” Alaina Roberts: I want to focus on the second part of that question, because that’s where I have more knowledge. In my book, I talk about what it looks like when African Americans come into Indian Territory in thousands, in droves. There is this kind of anger and frustration amongst some Indian freedpeople because Native American nations and individual Indian people get kind of scared because they see that they’re being overrun by these groups of people. They are a smaller population, African Americans are larger. And then along with white Americans coming in, there are all these people who are not part of their nation. Who yes, some of them steal cattle, some of them squat on their land. So, they don’t see this as a positive development and Indian freedpeople then see that this is affecting the way that they then view them. Because sometimes they’re grouped into this larger Black group and not seen as part of these Indian nations as they should be. And so it is a negative kind of experience. That is the tension that I talked about in the book, because we want to think of Black migration as good. It’s amazing that these people are trying to flee this white violence that they’re facing in the South, trying to build new homes and new communities for themselves. And yet, when we look at, honestly, some of the devastation that is wrought on Native nations and people by that migration, in addition to white migration, it’s a more complicated story. Because when someone else’s freedom means that you are being dispossessed, it’s more of a neutral than just a win and a celebratory story, I think. Now, there is one question, if you don’t mind, Cierra, that I wanted to respond to. So, Ean McCants is here, he’s attending. Ean is a fellow freedmen descendant as I am. And so he’s talking about reparations, and how there are some freedpeople who are uncomfortable with the way that I situate that. And I think that I wanted to highlight that because those are two separate identities for me sometimes. So, I’m a historian, I’m also a freedmen descendant. As a freedmen descendant, I understand that reparations, as I’ve said, are not clear cut. It doesn’t mean that Native nations treat people like my family any differently or think any differently about us. And they didn’t want to help our families. But I do think that when you look at the different parts of the federal government that are not just Henry Dawes, but are also the Secretary of Interior, James Harlan, also the Dawes commissioner, Commissioner Dole, all of these people have different ideas about what land means for Black people. And so even if they themselves have racist ideas about Black people, even if they themselves are not thinking about what that’s going to mean down the line in terms of incorporating this land into the United States, I still think it’s a historical moment that we have to acknowledge as different from what’s happening in the United States, and as part of a Reconstruction experiment. I’m not going to convince everyone and that’s totally fine. But I think as historians, when we look at the sources, we have to look at how people intend for projects to work. And we have lots of different parts of the federal government coming together to make a difference for at least my family. And the difference isn’t the same for everyone, certainly. It’s not a racial paradise even with these land allotments, but it is an important and different story. Cierra Kaler-Jones: I appreciate that. Thank you. I saw, too, that there was a follow-up question, as you were talking about the different ways that you looked into archives and Ancestry to tell the stories of your family. Roberta had asked specifically, “Did you use the records of the American Colonization Society?” Alaina Roberts: I did not, but I know what you’re getting at there. There is a book by a historian, her name is Kendra Field. The book is called Growing Up with the Country: Family, Race, and Nation After the Civil War, and she follows members of her family who traveled to Indian Territory and then to Africa. One of her great great ancestors became a leader who actually brought people to Africa. She talks about what we think of as a migration that is almost circular: you have people, African Americans, who are looking for this racial paradise that doesn’t exist, looking for a space where they really can create anew, aside from discrimination. So people go to Indian territory, they go to Kansas. We mentioned the exodusters. They go to California, they go to Liberia, looking for a place. And you know, of course, there is no perfect space. They sometimes stay at some of these spots, sometimes they move on, sometimes they go back to the South. But certainly that, again, is another important way of thinking about African American history that takes us not just out of the South, but also out of the Great Migration paradigm, I’d call it, because you have so much movement before then. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Wow, very interesting. As we near the end of our conversation today, I’m going to ask our last question before we invite folks for some feedback. Right now, we are living at a time where 42 states and counting have either introduced or passed legislation that bans teaching the truth about racism and oppression in schools. And much of the rich history that we’ve talked about today is either banned or may be banned in many places. So, what words of inspiration might you leave us with — this group of educators and activists and historians and students and loved ones and community members and librarians — what would you leave us with, as words of inspiration, as we continue to double down in our efforts to teach the truth, regardless of law, recognizing that you teach this truth everyday too? Alaina Roberts: Those of you who teach in K through 12, I feel like you are far more on the frontlines than I am. I have so much admiration for you all, because it’s scary out there now. I am thankful that you’re here tonight to learn from some of the work that I do, and I hope that you can find a way to incorporate it in your teaching in a way that makes you feel comfortable — and also really help students see themselves more in this historical narrative that often excludes not just people of color, but other narratives, like that of impoverished white people, of different kinds of inequality through economic hierarchies. I don’t know how to be inspiring, when really, I’m the one inspired by you all. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Oh, that’s so much appreciated, too. I see moving in the chatbox all of the educators that are like “We teach the truth, all day, every day.” So you are certainly in good company. I know that so many folks will take everything that they’ve learned today and bring it back to their classrooms, whatever their classrooms might look like at this time. Thank you so much for sharing your expertise, for sharing your stories, for sharing your family’s stories, with all of us. It’s so appreciated to be able to learn about these narratives, to have a more expansive view of history. It helps us to learn the truth and how we can really take that truth as a launching pad to be in solidarity with one another, to be able to create the world that we all deserve to live in. While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, articles, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula

|

40 Acres and a Mule: Role-Playing What Reconstruction Could Have Been by Adam Sanchez (lesson) The Color Line by Bill Bigelow (lesson) How to Make Amends: A Lesson on Reparations by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, Alex Stegner, Chris Buehler, Angela DiPasquale, and Tom McKenna (lesson) Repair: Students Design a Reparations Bill by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (lesson) Teaching a People’s History of Abolition and the Civil War edited by Adam Sanchez (teaching guide) |

Related Books

|

I’ve Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land by Alaina Roberts (University of Pennsylvania Press) An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States for Young People by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (Beacon Press) I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction by Kidada E. Williams (Bloomsbury Publishing; expected release date of January 2023) Black Birds in the Sky: The Story and Legacy of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre by Brandy Colbert (Balzer & Bray/Harperteen) Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies edited by Kinshasha Holman Conwill and Paul Gardullo (Amistad) The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition by Manisha Sinha (Yale University Press) |

Related Articles and Resources

|

Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction report (with an Oklahoma vignette featuring Dr. Roberts’ book). Dawes Rolls from the National Archives This Land podcast on Crooked Media |

This Day In History

|

May 23, 1838: The Trail of Tears Began March 3, 1865: Freedmen’s Bureau Established June 25, 1876: Battle of the Greasy Grass (Battle of Little Big Horn) April 18, 1877: Nicodemus Town Company Founded Feb. 20, 1884: Indian Industrial School Opens in Nebraska Feb. 20, 1885: Black Town of Princeville, North Carolina Incorporated May 31, 1921: Tulsa Massacre |

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

There was no one experience of enslavement.

Really appreciated the nuance around reparations — is it valid if it comes from a group other than the one that caused harm? How can they be framed (supported, hindered) when framed against systems of white supremacy?

The multilayered impact of the Dawes Act and possible framing within reparations discussion.

How the U.S. government used land during reparations to further divide Indigenous & Black solidarity was fascinating and disturbing.

I learned to look more closely at the ways in which People of Color have been brought together as well as torn apart by white supremacy through some tribes adoption or rejection of chattel slavery and Black/Indigenous solidarity through history!

The complexity of reparations when other people’s land becomes the compensation for a national tragedy.

I think it was powerful to learn how complex and nuanced the story of land and reparations and reconciliation is in the so-called U.S.

What will you do with what you learned?

I am rearranging so much furniture in my head right now. Know better, do better. I am really looking forward to applying more nuances to my Reconstruction lessons.

I will be forced to reconcile this important nuance in the teaching of the history of slavery in the U.S. with the general backlash against the teaching of “peoples history,” and will have to find creative ways to introduce this contentious reality without it being used to cause division or in bad faith attempts to discount the teaching of Black or Indigenous freedom struggles.

I’m a teacher of Georgia Studies/Georgia History. I plan to add these tidbits of wisdom to conversations we’ve already been having about Native Removal, the Maroon communities, as well as Black and Red Power Movements.

This will serve as a helpful foundation and background knowledge as we transition from the Harlem Renaissance Unit to reading Angel of Greenwood by Randi Pink talking about Black success in Greenwood, Oklahoma and the Tulsa Race Massacre that followed.

I want to interweave this history into our study and work about indigenous people, but mostly it reminds me to continue to dig into history and find ALL the voices and perspectives. In many ways it teaches students to hold complexity.

I will be very selective of the resources that I use in class. It must be based on facts, not over generalized, and include perspectives that are historically suppressed.

I will bring the nuanced challenges of reparations model within Indian territory as an example of reparations for formerly enslaved people as students examine and design reparations proposals, as well as highlighting the distinct differences/separateness of the United States as distinct from Indian Territory and Indigenous tribal sovereign land, into my civics class. I am fascinated to learn more about the split in the Creek Nation over the issue of slavery. I will put more study and attention into the Black west, and I can’t wait to read Dr. Roberts’ book.

Presenters

Alaina Roberts, the author of I’ve Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land, is an award-winning historian who studies the intersection of Black and Native American life from the Civil War to the modern day. She is an assistant professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh. She writes, teaches, and presents about Black and Native history in the West, family history, slavery in the Five Tribes (the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole Indian Nations), Native American enrollment politics, and Indigeneity in North America and across the globe.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is a social justice educator, writer, and researcher based in Washington, D.C. Her research explores how Black girls use arts-based practices as mechanisms for identity construction and resistance. She is the director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund and on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn