Dancer at Juneteenth celebration in Washington, D.C. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Source: Library of Congress

Juneteenth — June 19th, also known as Emancipation Day — is one of the commemorations of people seizing their freedom in the United States.

Celebrate. But We Can’t Teach?

This beautiful tradition of Black freedom should be taught in school.

Yet, if the right wing has its way, it will be illegal to teach students about Juneteenth. At least 44 states have passed or proposed legislation to prohibit teaching about structural racism. The goal of conservative legislators: to outlaw teaching about the founding of this country on slavery and genocide or the long Black freedom struggle.

Some statewide bills ban teaching about the very structures and systems that led to enslavement as well as how these structures continue to manifest in policing, redlining, voter suppression laws, and more.

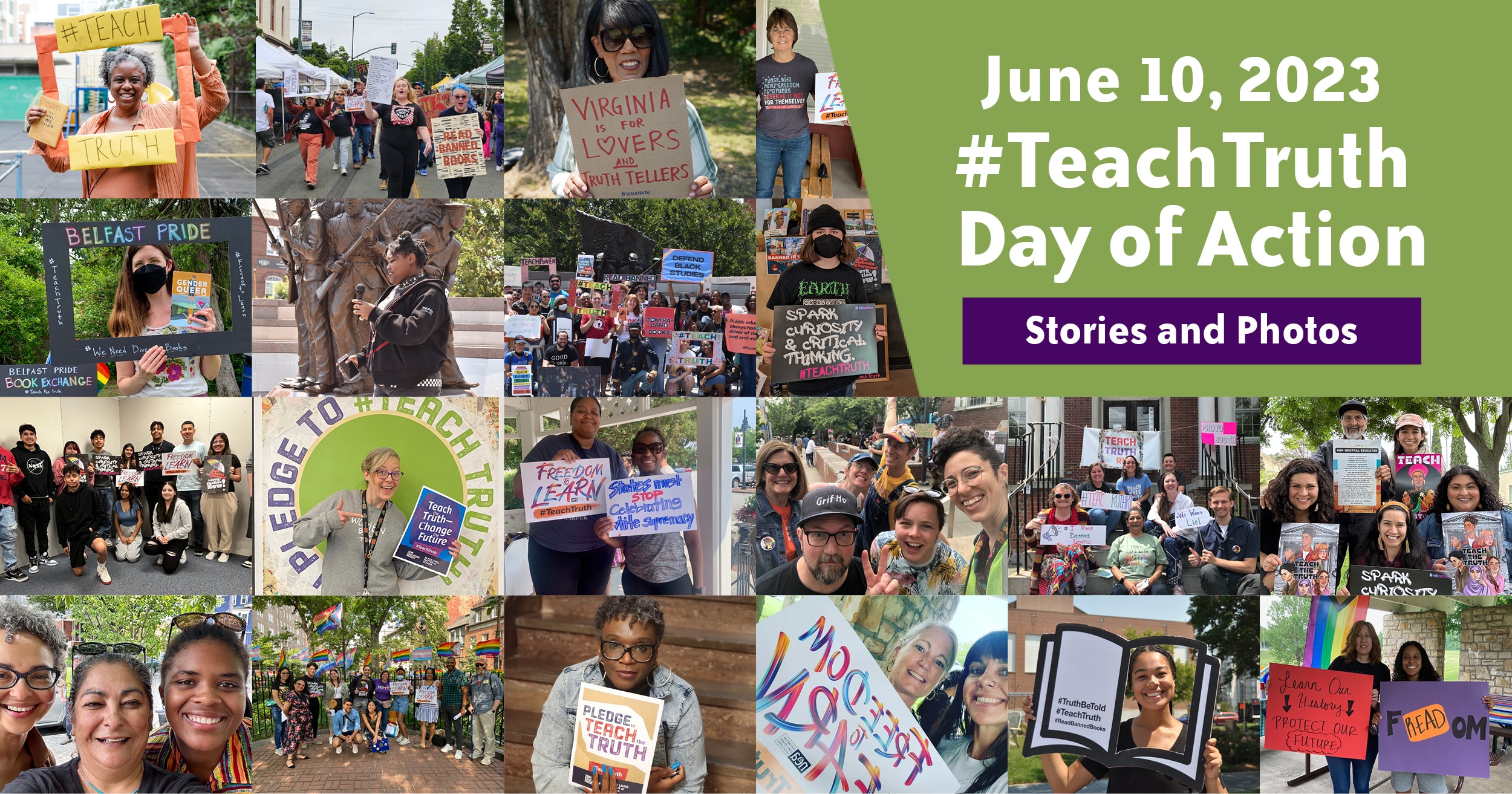

But educators around the country continue to pledge to teach the truth about structural racism.

Last weekend, teachers in at least 65 cities joined the national #TeachTruth Days of Action. They rallied to defend the right to teach truthfully, to protest book bans, and to defend LGBTQ+ rights.

It is time to redouble our commitment to teach about the long Black freedom struggle, including Juneteenth.

Background on Juneteenth

Here are key points from scholars Greg Carr, Christopher Wilson, and Clint Smith on the history beyond the traditional textbook narrative about Juneteenth.

Black Troops Spreading the Word with Every Marching Foot

By Howard University professor Greg Carr, transcribed from a Teach the Black Freedom Struggle Online Class

While General Granger read the Emancipation Proclamation off that veranda in Galveston, there were at least nine regiments of the United States Colored Troops marking their way through Texas, the last of the 10 states in the Confederacy to give up. Black troops, some of those same Black troops that have captured Richmond, those Black troops were now in Texas. So while Granger makes the formal announcement on June 19th, and a year later to the day, Black folks start celebrating Juneteenth formally, those Black troops are spreading the word with every marching foot as they come across the South.

June 19th is the official day marking these emancipation celebrations as it formally comes into the African awareness in Texas. But the dates are usually linked to whenever people found out they were free, which is why in Mississippi, in Alabama, in Arkansas, in Oklahoma, you might see an August date or July date. This is described in O Freedom: Afro-American Emancipation Celebrations by William Wiggins. What we see in Galveston, Texas, in 1865, is also connected to the Caribbean, described in Howard University professor Jeffrey Kerr-Ritchie’s book on Emancipation Day celebrations called Rites of August First: Emancipation Day in the Black Atlantic World. There is also Decoration Day. We think about the roots of what become Memorial Day, the idea of honoring our ancestors who made the ultimate sacrifice, by placing flowers on their graves and you see that coming out of South Carolina. There’s a very good book called Conjuring Freedom that talks about that South Carolina regiment of Colored Troops and the beautiful Ed Dwight monument on the South Carolina State House grounds.

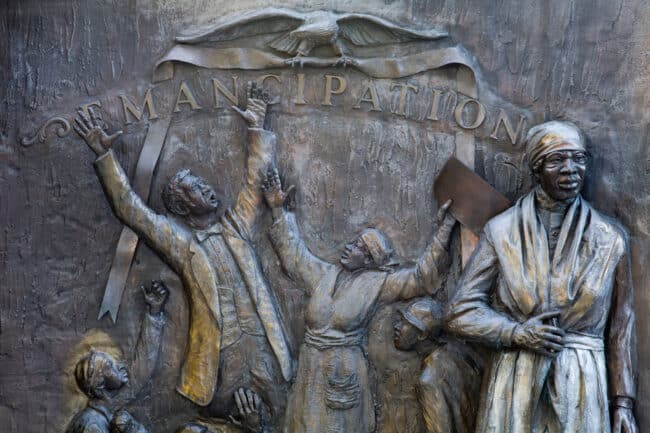

African American History Monument by Ed Dwight, State Capitol Grounds, Columbia, South Carolina. Source: Alamy

. . .In many of the churches in the North — Boston, Philadelphia, New York — people prayed on the last day of December 1862. They brought in the New Year with the expectation that now it was time to get up off our knees, go get some guns or support those with guns, and make this Emancipation Proclamation stand up since it didn’t apply unless you were in control of the place that you went to in battles.

And, of course, January 1 was the celebration day for a lot of Black people for years because of the Emancipation Proclamation. Minister Silas X. Floyd said, “May God forget my people, if we forget this day,” and that was January 1, not June 19. That’s another one of many examples.

It Was Not the “News” That Traveled Slowly — It Was “Power”

By Christopher Wilson, Experience Design Director, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History

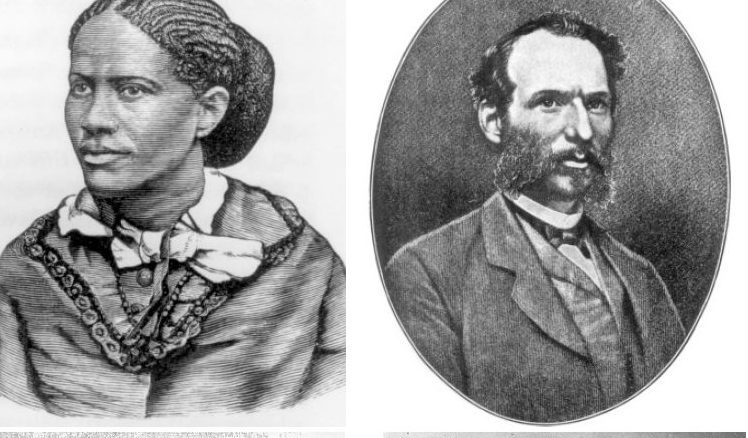

Very often Juneteenth is presented as a story of “news” of the Emancipation Proclamation “traveling slowly” to the Deep South and Texas, but it was really a story of power traveling slowly, and of freedom being seized. Due to the telegraph, newspapers and the United States Army spread out all across the country to put down the slaveholders’ rebellion, word of Lincoln’s order spread all over the South immediately after it was announced in September 1862 and took effect in January 1863.

While enslaved Black people in far off places like Texas were often kept in the dark and fed a pro-slavery narrative of the events of the war and the nation, whether they received word of the order wasn’t so much the point. As with an incarcerated prisoner who may be told she’s free, until the prison bars are unlocked that word only results in theoretical freedom. The news that the United States government was declaring enslaved people in areas still in rebellion against the nation forever free was incredibly important to the enslaved and the country, but what mattered more than that news was the power and will to enforce it. General Granger’s order was less directed toward offering news to the enslaved than it was about commanding lawless human traffickers and insurrectionists to obey the Proclamation issued two years earlier.

While enslaved Black people in far off places like Texas were often kept in the dark and fed a pro-slavery narrative of the events of the war and the nation, whether they received word of the order wasn’t so much the point. As with an incarcerated prisoner who may be told she’s free, until the prison bars are unlocked that word only results in theoretical freedom. The news that the United States government was declaring enslaved people in areas still in rebellion against the nation forever free was incredibly important to the enslaved and the country, but what mattered more than that news was the power and will to enforce it. General Granger’s order was less directed toward offering news to the enslaved than it was about commanding lawless human traffickers and insurrectionists to obey the Proclamation issued two years earlier.

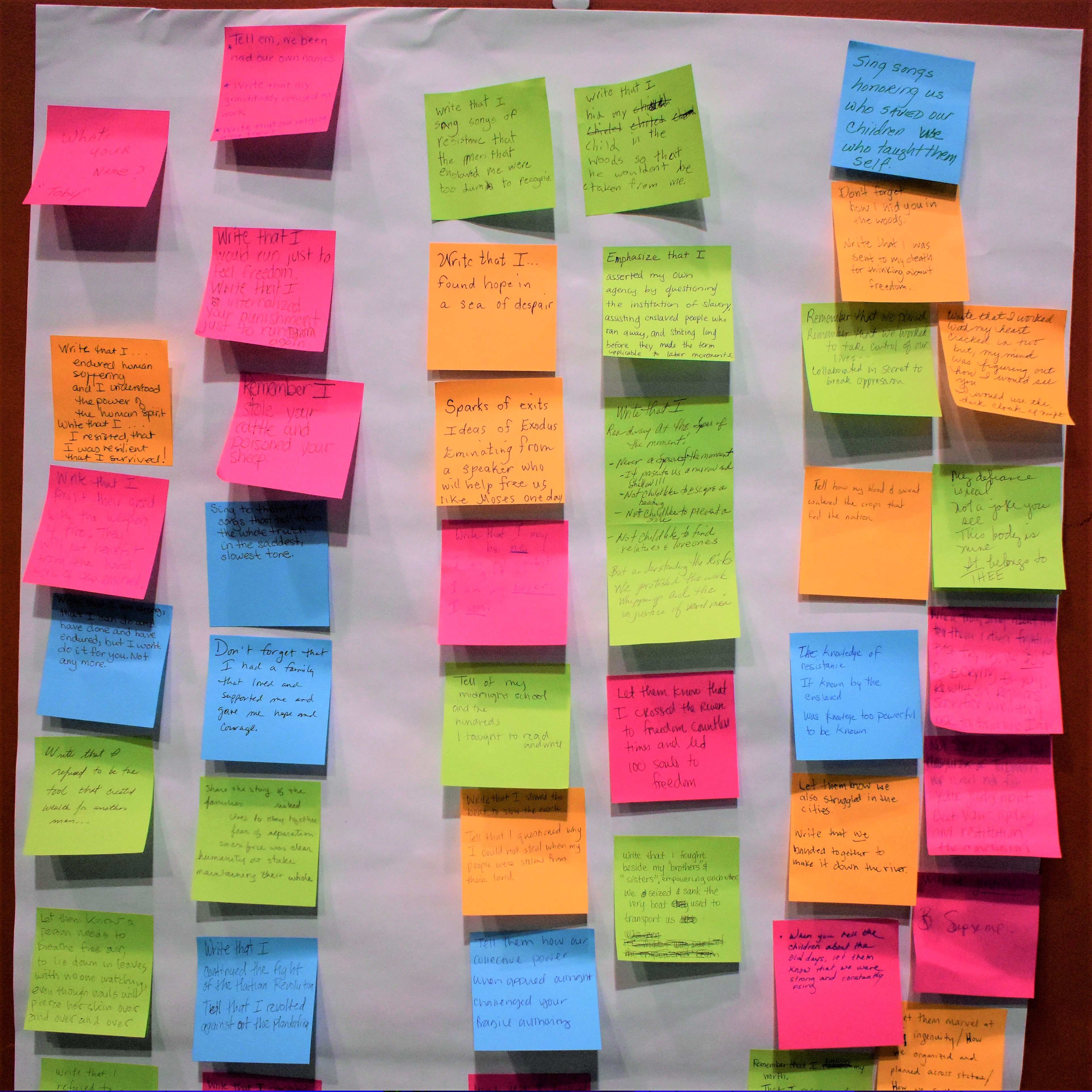

Even following the arrival of the power to enforce the emancipation order in the form of the United States Army, enslaved people were left with much of the responsibility to seize their own freedom. As had been the case since the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, the position of the federal government on ending slavery in much of the country offered the enslaved the chance to take their freedom into their own hands and promised that if they could get themselves to an area not controlled by rebels, that this theoretical freedom would be fulfilled. This drive and requirement for self-emancipation has been consistent through the story of Black American history.

The Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 made school segregation unconstitutional, but it was men, women and children who put their bodies on the line to actually desegregate schools years later. The Morgan v. Virginia decision in 1946 made segregation on interstate buses unconstitutional, but it was Freedom Riders who were beaten and burned who desegregated transit in 1961.

The promise of freedom implied in the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation was real and very important, as was the eventual enforcement of that order by the Army across the South and into Texas, but the enslaved were ultimately the ones to truly decide what freedom meant to them and who worked to make it a reality.

Long History of Commemorations

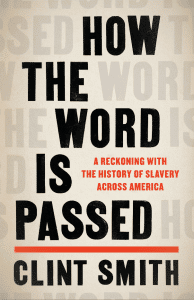

By journalist and educator Clint Smith, in an excerpt from his 2021 book, How the Word Is Passed (page 187)

The earliest iterations of Juneteenth in Texas, which began following the end of the Civil War, ranged from ceremonial readings of the Emancipation Proclamation to Black newspapers printing images of Abraham Lincoln in their pages, testament to a man who had already begun to take on a legendary and even mythical status among many in the Black community.

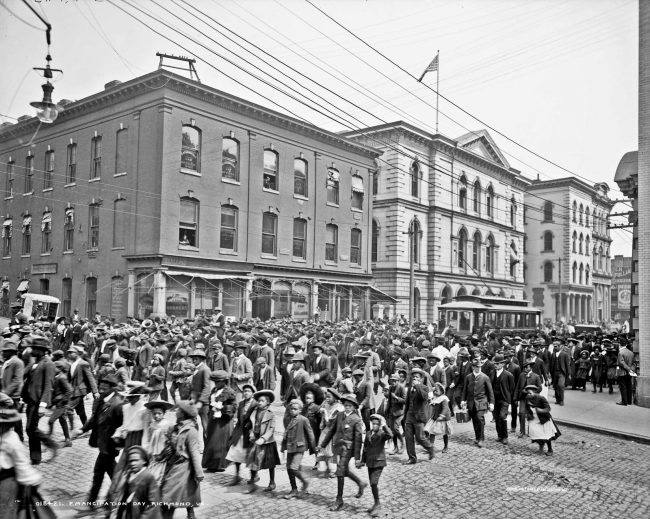

Parade in Richmond, Virginia for Emancipation Day, April 3, 1905. Source: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries

Other celebrations included church services in which preachers had the congregation give thanks for their freedom while encouraging them to be relentless in the ongoing struggle for racial equity. Often there were parades, large displays of song and celebration that shook the street. And in the afternoons there were massive feasts, the sort of spread that people looked forward to all year: spareribs, fried chicken, black-eyed peas. . . .

Other celebrations included church services in which preachers had the congregation give thanks for their freedom while encouraging them to be relentless in the ongoing struggle for racial equity. Often there were parades, large displays of song and celebration that shook the street. And in the afternoons there were massive feasts, the sort of spread that people looked forward to all year: spareribs, fried chicken, black-eyed peas. . . .

With the threat of lynching always there for Black Southerners, some celebrations across the country disappeared from public view and into private homes and Black churches.

Teaching Resources

|

Watch Professor Greg Carr’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle conversation with high school teacher Jessica Rucker about Juneteenth and Reconstruction. |

The National Museum of African American History and Culture offers the digital resource, Juneteenth: Celebration of Resilience. |

Also recommended: Juneteenth Observances Promote ‘Absolute Equality’ by Coshandra Dillard in Learning for Justice.

Find related classroom resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn