By Adam Sanchez

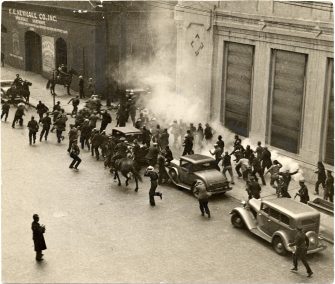

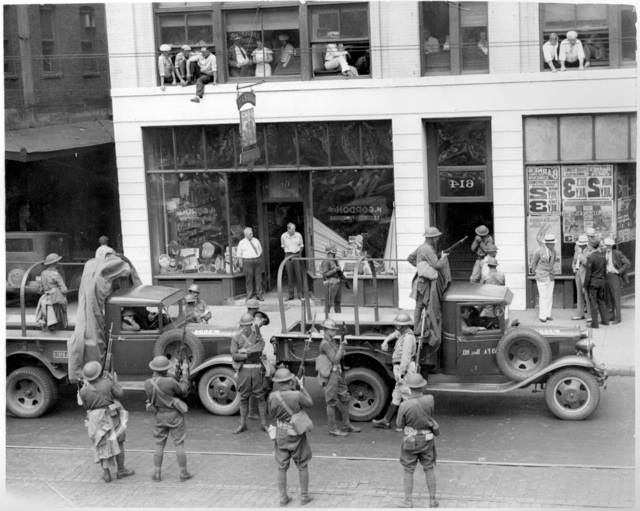

Police use tear gas against participants in San Francisco’s 1934 general strike. Source: San Francisco Public Library.

Most historians, and many textbooks, divide the New Deal into two phases: the first New Deal, the flurry of legislation during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first 100 days, and the second New Deal, the more sweeping and long-lasting legislation passed in 1935. They describe this as an era when the government experimented with new and different programs aimed at the same goal: economic recovery. In Roosevelt’s words: “It is common sense to take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

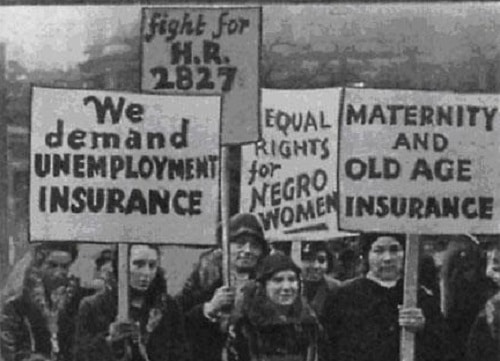

Unfortunately, mainstream histories ignore the social forces pressing for more radical New Deal legislation and fail to explain how the dynamics of power shifted in response to a growing struggle from below.

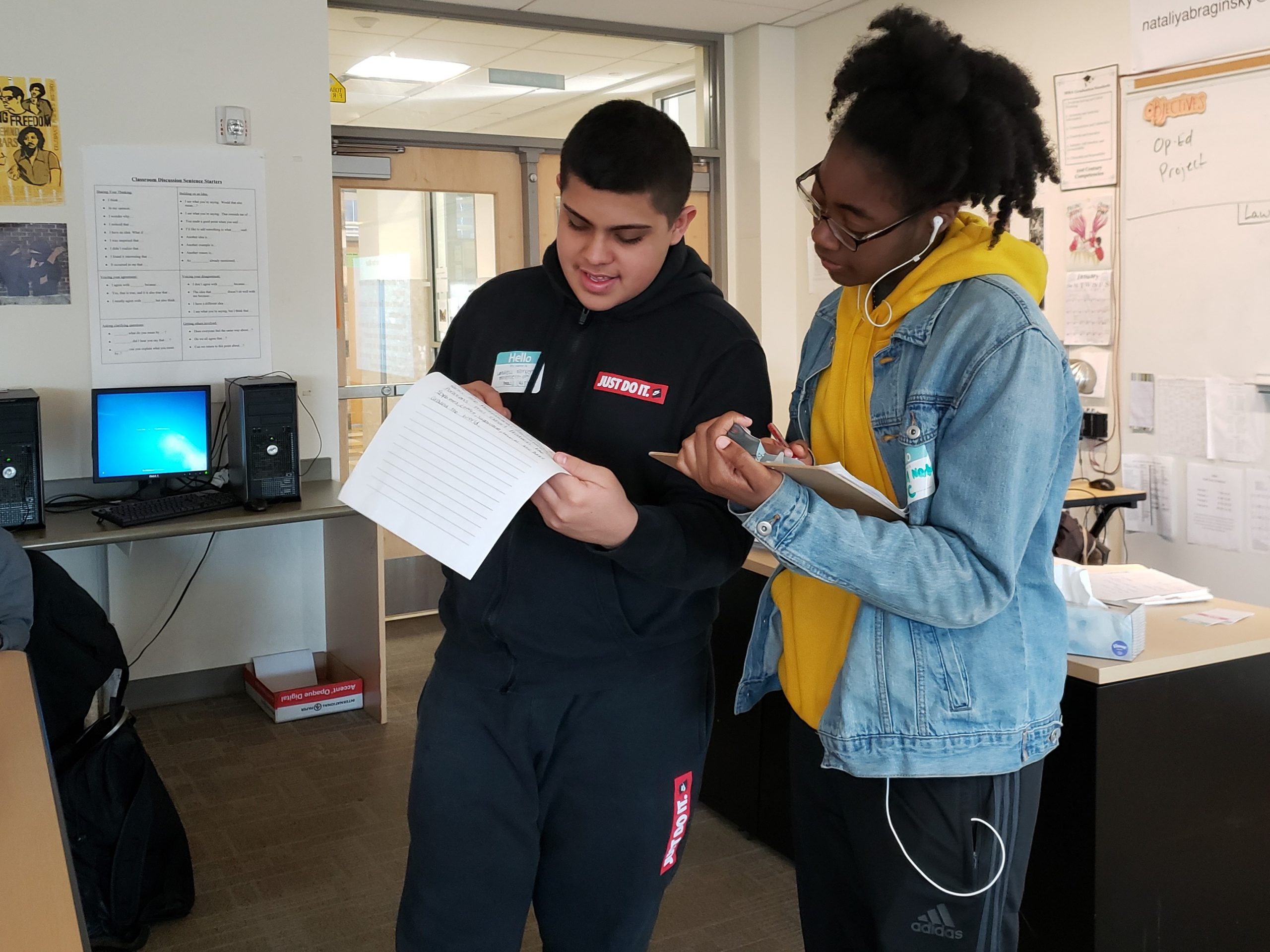

To help students grapple with the legislation of the early New Deal, I developed the Economic Recovery Conference Role Play. The goal of this role play is to help students understand who among the public supported this early legislation and why.

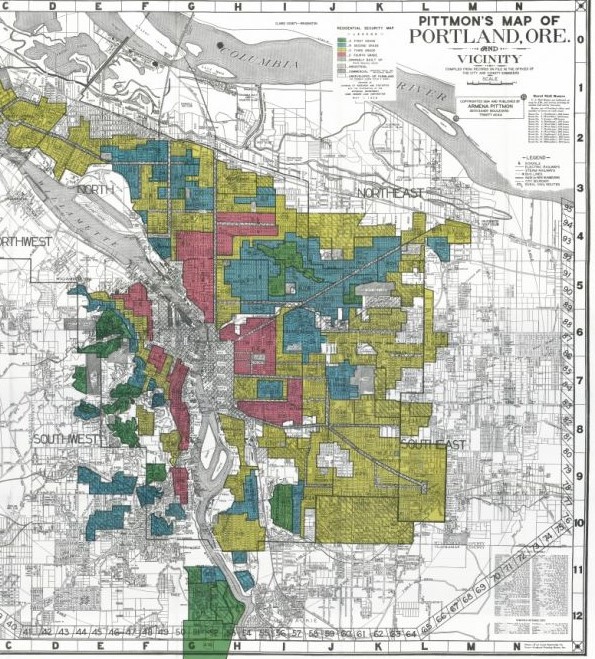

After exploring the causes of the Great Depression (see What Caused the Great Depression?), my 10th-grade U.S. History class at Madison High School in Portland, Oregon, read about the emergence throughout the country of Unemployed Councils. We also read about the Bonus Army’s 1932 occupation of Washington, D.C.

Together, these stories make a compelling case that the decisive blow ending the Hoover presidency was not Roosevelt’s charismatic speeches on the campaign trail, but the militant actions of ordinary people whose lives were devastated by the crisis. Like capitalists today, the business community supported government spending when it helped increase their business’ profits, but not as a policy to curb unemployment. I wanted students to imagine the early New Deal within the context of other economic solutions on offer at the time.

This article was first published in Rethinking Schools magazine Volume 30, No. 2 in Winter 2015/2016. Rethinking Schools offers a series of books providing practical examples of how to integrate social justice education into social studies, history, language arts, and mathematics. They are used widely by new as well as veteran teachers and in teacher education programs. Visit www.rethinkingschools.org to learn more and subscribe.

This article was first published in Rethinking Schools magazine Volume 30, No. 2 in Winter 2015/2016. Rethinking Schools offers a series of books providing practical examples of how to integrate social justice education into social studies, history, language arts, and mathematics. They are used widely by new as well as veteran teachers and in teacher education programs. Visit www.rethinkingschools.org to learn more and subscribe.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn