By the Pearl Coalition

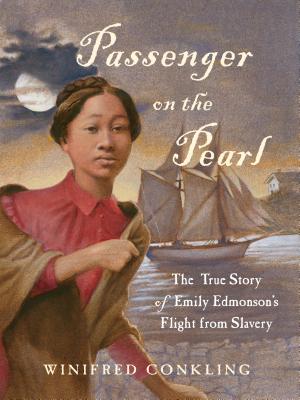

“One hundred dollars” is what Daniel Bell, a free African American blacksmith living and working at the Navy Yard in the District of Columbia, was told he needed for his family in 1848. Eleven members of his family — including his wife, children, and grandchildren — could escape from slavery for $100 (today’s equivalent of a half year’s pay). Legally they were already free, but lawyers had them tied up in court. Proving their freedom would be expensive, time consuming, and uncertain at best. A ship could be chartered, The Pearl, to take his family to freedom.

It had been done before and they could get the same captain do it again. Working with two other African Americans living in Washington, D.C. — Samuel Edmonson (who wanted to help his enslaved sisters, Emily and Mary), and Paul Jennings (in the process of “paying down the balance of the debt owed for his freedom,” formerly enslaved to President and Mrs. Madison) — Bell would make it happen; he would get the $100. Captain Daniel Drayton took the chance because he needed the money. He chartered The Pearl and brought it to the 7th street wharf in D.C. during the great public demonstrations celebrating the establishment of the new French Republic, the exile of King Louis-Philippe and the hope for universal liberty. Washington, D.C. was aglow with excitement.

The cargo schooner could hold more than the enslaved members of the Bell and Edmonson families. Others learned of the daring plan and asked to join. Drayton accepted all those who could get on board by midnight. Casting off in the dark, they sailed down the Potomac, escaping to their freedom. The largest slave escape in the history of the United States was in progress.

The cargo schooner could hold more than the enslaved members of the Bell and Edmonson families. Others learned of the daring plan and asked to join. Drayton accepted all those who could get on board by midnight. Casting off in the dark, they sailed down the Potomac, escaping to their freedom. The largest slave escape in the history of the United States was in progress.

Forty-one slave owners in Washington, Maryland, and Virginia awoke the next day to discover 77 people missing. Banding together on the steamer Salem, organized by the then Justice of the Peace, law enforcement officers and others, a posse of 35 armed white men headed out in hot pursuit of The Pearl. Winds pouring down the Chesapeake had forced The Pearl to anchor, waiting for a weather change, and the ship and its passengers were apprehended. The pursuit of family freedom was stymied, but many of the families on The Pearl survived and, when freedom came, they thrived.

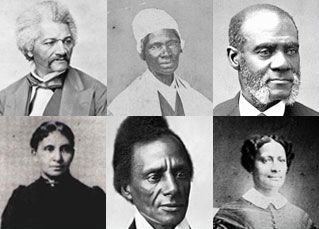

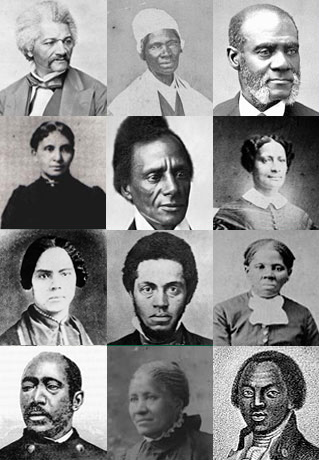

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law Convention, Cazenovia, New York. The Edmonson sisters are standing wearing bonnets and shawls in the row behind the seated speakers. Frederick Douglass is seated, with Gerritt Smith standing behind him, and with Abby Kelley Foster the likely person seated on Douglass’s left. Source: WikiCommons

Above, Frederick Douglass is pictured with Mary and Emily Edmonson at the Cazenovia Fugitive Slave Law Convention in New York. The New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington D.C. Underground Railroad cell(s) were very involved in the planning, organization, and implementation of the escape.

Above, Frederick Douglass is pictured with Mary and Emily Edmonson at the Cazenovia Fugitive Slave Law Convention in New York. The New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington D.C. Underground Railroad cell(s) were very involved in the planning, organization, and implementation of the escape.

People of faith and the church of that time served as the life blood for communications and the driving force behind the movement to abolish slavery locally and nationally. The escape on the Pearl Schooner reignited the abolitionist movement. Thus, it led to a series of events and congressional and presidential actions that later laid the foundation for the emancipation of slavery in Washington D.C., the Emancipation Proclamation, and the Civil War.

This article was originally published on The Pearl Coalition website.

Learn More

Read more about the escape on the Pearl at the Washington Post.

Listen to a musical tribute to Emily and Mary Edmonson, composed by Joe DeFilippo and performed by the R. J. Phillips Band, a group of Baltimore musicians: “Troubled Waters.”

Find related resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn