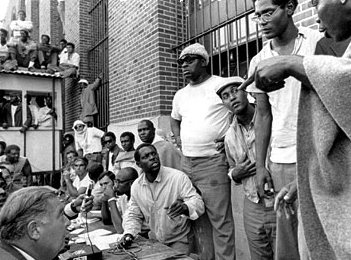

Attica prisoners raise fists in support of demands made during prison uprising, Sept. 10, 1971.

From Sept. 9 to 13, 1971, prisoners took control of the Attica Correctional Facility in the most well-known prison uprising of the 20th century. They made a series of demands to prison administrators and held about 40 people as hostages. Their demands were included in a Manifesto that began:

We, the men of Attica Prison, have been committed to the New York State Department of Corrections by the people of society for the purpose of correcting what has been deemed as social errors in behaviour.

The program which we are submitted to under the façade of rehabilitation are relative to the ancient stupidity of pouring water on a drowning man, inasmuch as we are treated for our hostilities by our program administrators with their hostility as medication.

In our peaceful efforts to assemble in dissent as provided under this nation’s U.S. Constitution, we are in turn murdered, brutalized, and framed on various criminal charges because we seek the rights and privileges of all American People.

In our efforts to intellectually expand in keeping with the outside world, through all categories of news media, we are systematically restricted and punitively remanded to isolation status when we insist on our human rights to the wisdom of awareness. [See full Manifesto of Demands in Attica Prison Uprising 101: A Short Primer.]

Inmates of Attica state prison, right, negotiate with state prisons Comm. Russell Oswald, lower left, at the facility in Attica, NY, 9/10/1971.

As Howard Zinn explains in A People’s History of the United States:

The most direct effect of the George Jackson murder was the rebellion at Attica prison — a rebellion that came from long, deep grievances. . . . 54% of the inmates were black; 100% of the guards were white. Prisoners spent 14 to 16 hours a day in their cells, their mail was read, their reading material restricted, their visits from families conducted through a mesh screen, their medical care disgraceful, their parole system inequitable, racism everywhere.

After four days of fruitless negotiations, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller ordered that the prison be retaken; 39 people were killed in a 15-minute assault by state police.

The New York State Special Commission on Attica (also known as the McKay Commission) appointed to investigate the uprising suggested: “With the exception of Indian massacres in the late 19th century, the State Police assault which ended the four-day prison uprising was the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War.”

The New York State Special Commission on Attica (also known as the McKay Commission) appointed to investigate the uprising suggested: “With the exception of Indian massacres in the late 19th century, the State Police assault which ended the four-day prison uprising was the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War.”

The uprising did not come out of nowhere. In September 1971 at Attica prison, there were over 2,200 people locked up in dehumanizing conditions in a facility built to accommodate 1,600.

In 1970, there were 48,497 people in federal and state prisons in the U.S. By 2009, there were 1,613,740 individuals locked up in our federal and state prisons.

This exponential growth of the prison population means that the events of Attica are as relevant today as they were in 1971; perhaps even more so. There is a continued need to investigate the conditions of our prisons today and to advocate for an end to mass incarceration. [Adapted from the introduction to Attica Prison Uprising 101: A Short Primer.]

Resources for Teaching About the Attica Prison Uprising

|

Attica Prison Uprising 101: A Short Primer Free and downloadable. Produced by Project NIA. |

|

A Story of Attica Short version of the primer listed above. Free. |

|

Eyes on the Prize features a segment on Attica (“A Nation of Law? (1968-71)”) with primary documents, interviews, and video. |

|

Attica, a 1974 documentary film by Cindy Firestone. Ghosts of Attica, a 2001 documentary by David Van Taylor and Brad Lichtenstein, narrated by Susan Sarandon. Democracy Now! broadcast about Frank “Big Black” Smith, a prisoner who was tortured after the rebellion. Additional resources below, including Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. |

Classroom Story

For my 12th grade remedial English class, I often use graphic novels to teach students reading and writing skills. These are students who often have learning disabilities and/or English is not their first language. They also all have not passed the New York Regents Examination for ELA yet, so the class is designed to prepare them for it. They cannot graduate without passing that exam.

Knowing the stakes, I acquired an advanced copy of Big Black: Stand at Attica and made photocopies of key pages for the students. We have begun exploring different sections of the book. Students had no knowledge of the topic previously and were awestruck by the history.

For their assignment, students worked on a choice of two essay topics where they had to state and defend an argument. The first topic was about the merits of the prison system in general and whether or not it’s good for society. The other topic is about whether or not prisoners are entitled to the same rights as non-prisoners. Both essay topics are aligned to the Regents Examination. This way, my students learned important history while simultaneously mastering the language skills required to advance past New York’s oppressive standardized testing system.

The students in my African American History class became particularly interested in the mass incarceration of Black Americans after learning about the systems put in place in Jim Crow America to limit the freedoms promised by the 13th Amendment, to include sharecropping, tenant farming, chain gangs, debt slavery, etc. We drew connections to modern America by viewing the Netflix documentary, 13th.

The resources at the Zinn Education project on the Attica Prison Uprising were a perfect addition to this student-driven unit. We read the demands created by the Attica prisoners and turnkeyed the theme into creating a list of themes for our school.

Students expressed feeling targeted by our school security for dress code and tardy violations disproportionately compared to their white peers. By creating a list of demands similar to the Attica Uprising, students felt empowered and like they had an official voice for the administration to consider. We were even able to get our principal to come into our class for a thinktank as a results of the lists.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn