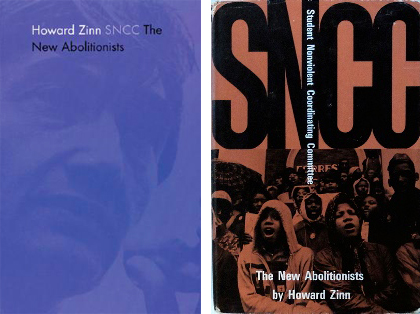

On January 22, 1964, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) voting rights campaign held a Freedom Day in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Below is a description from the Civil Rights Movement Archive. There is also a detailed description by Howard Zinn who were there that day.

By Civil Rights Movement Archive

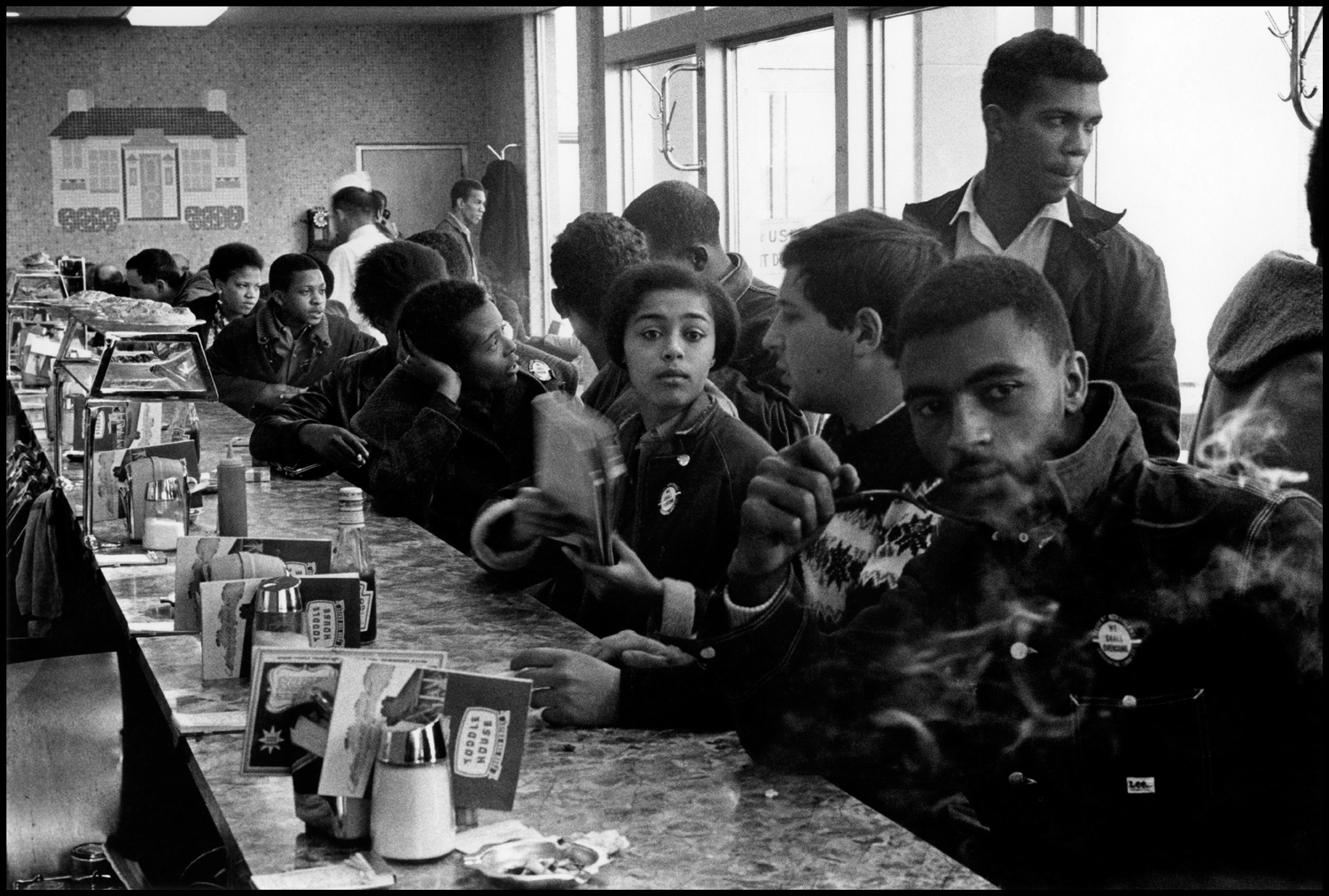

January 22nd, 1964, is Freedom Day in Hattiesburg. A cold rain is falling. Fifty African Americans, mostly students plus a few adults, plus thirty of the northern clergy, picket the Forrest County courthouse. Some carry signs with SNCC’s new slogan, “One Man One Vote.” Close to 100 Black adults are lined up at the building to register, their numbers dwarfing all previous attempts.

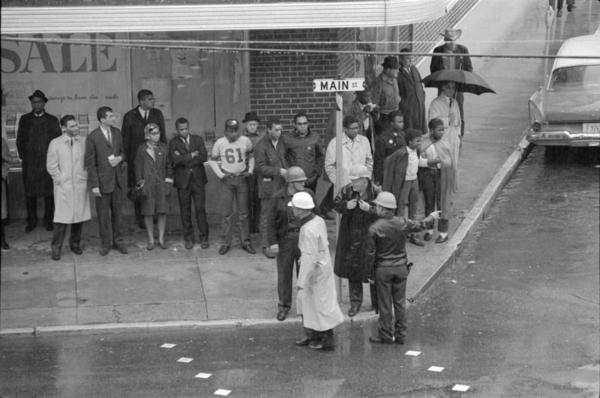

A phalanx of cops and volunteer “auxiliary police” (possemen) in helmets and rain slickers, guns on their hips, clubs in their hands, march down the middle of Main Street towards the protesters. Using a bullhorn, they issue their order: “This is the Hattiesburg Police Department. We’re ordering you to disperse. Clear the sidewalk!” The pickets hold the line. No one leaves. The cops threaten again. The pickets hold. SNCC leader Bob Moses is arrested for “Disturbing the Peace” when he tries to escort an elderly Black women into the courthouse to register. But none of the pickets are arrested. For the first time in living memory, an inter-racial civil rights demonstration in Mississippi is not suppressed. As it becomes clear there won’t be a mass jailing, more people join the picket line, swelling it to over 200 who by the end of the day are massed on the courthouse steps singing freedom songs .

Theron Lynd allows only four voter applicants at a time into the building. He slowly takes as long as he can to process each application. Meanwhile, the other applicants continue to stand in the cold rain waiting their turn. Whites are allowed to freely enter the building, but African Americans are not. Justice Department officials and FBI agents take notes, but refuse to intervene. When the courthouse is closed at noon for lunch, only 12 applicants have been processed. The rain, the waiting, and the pickets continue all day until the courthouse closes at 5pm.

Yale graduate Oscar Chase, a white member of SNCC, is arrested on a phony vehicle charge. He is put in a cell with white prisoners who beat him into bloody unconsciousness while the guards watch. The most brutal of the white inmates is rewarded with early release. After Chase is bailed out the next morning, historian Howard Zinn and two Freedom Movement lawyers take him to the FBI office to file a complaint. His clothes are covered with blood, his nose broken, and his face swollen and bruised. The FBI agent studies the clean-shaven college professor, the two lawyers in their neatly-pressed suits, and the battered freedom fighter. “Who was it got the beating?” he asks.

Freedom Day is considered a Movement victory. The pickets are not dispersed by police billy clubs, nor are there mass arrests. More than 150 Forrest County African Americans defy generations of repression by trying to register. Theron Lynd is forced to allow at least some of them into the office to fill out the application and take the literacy test. But it is only a partial victory. Neither the Justice Department nor the FBI enforce the Constitution, federal law, or court orders to protect voting rights and few, if any, African Americans are actually registered. And when some of those who protested or attempted to register are later fired from their jobs, the federal government does nothing. [From Civil Rights Movement Archive.]

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn