By Bill Bigelow

Once again this year many schools will pause to commemorate Christopher Columbus. Given everything we know about who Columbus was and what he launched in the Americas, this needs to stop.

Columbus initiated the trans-Atlantic slave trade, in early February 1494, first sending several dozen enslaved Taínos to Spain. Columbus described those he enslaved as “well made and of very good intelligence,” and recommended to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella that taxing slave shipments could help pay for supplies needed in the Indies. A year later, Columbus intensified his efforts to enslave Indigenous people in the Caribbean. He ordered 1,600 Taínos rounded up — people whom Columbus had earlier described as “so full of love and without greed” — and had 550 of the “best males and females,” according to one witness, Michele de Cuneo, chained and sent as slaves to Spain. “Of the rest who were left,” de Cuneo writes, “the announcement went around that whoever wanted them could take as many as he pleased; and this was done.”

Taíno slavery in Spain turned out to be unprofitable, but Columbus later wrote, “Let us in the name of the Holy Trinity go on sending all the slaves that can be sold.”

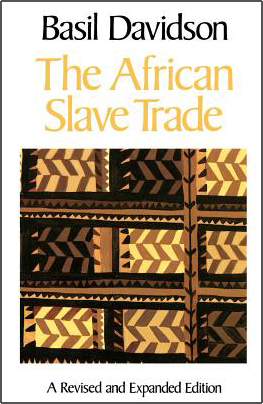

The eminent historian of Africa, Basil Davidson, also assigns responsibility to Columbus for initiating the African slave trade to the Americas. According to Davidson, the first license granted to send enslaved Africans to the Caribbean was issued by the king and queen in 1501, during Columbus’s rule in the Indies, leading Davidson to dub Columbus the “father of the slave trade.”

The eminent historian of Africa, Basil Davidson, also assigns responsibility to Columbus for initiating the African slave trade to the Americas. According to Davidson, the first license granted to send enslaved Africans to the Caribbean was issued by the king and queen in 1501, during Columbus’s rule in the Indies, leading Davidson to dub Columbus the “father of the slave trade.”

From the very beginning, Columbus was not on a mission of discovery but of conquest and exploitation — he called his expedition la empresa, the enterprise. When slavery did not pay off, Columbus turned to a tribute system, forcing every Taíno, 14 or older, to fill a hawk’s bell with gold every three months. If successful, they were safe for another three months. If not, Columbus ordered that Taínos be “punished,” by having their hands chopped off, or they were chased down by attack dogs. As the Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas wrote, this tribute system was “impossible and intolerable.”

And Columbus deserves to be remembered as the first terrorist in the Americas. When resistance mounted to the Spaniards’ violence, Columbus sent an armed force to “spread terror among the Indians to show them how strong and powerful the Christians were,” according to the Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas. In his book Conquest of Paradise, Kirkpatrick Sale describes what happened when Columbus’s men encountered a force of Taínos in March of 1495 in a valley on the island of Hispañiola:

The soldiers mowed down dozens with point-blank volleys, loosed the dogs to rip open limbs and bellies, chased fleeing Indians into the bush to skewer them on sword and pike, and [according to Columbus’s biographer, his son Fernando] “with God’s aid soon gained a complete victory, killing many Indians and capturing others who were also killed.”

All this and much more has long been known and documented. As early as 1942 in his Pulitzer Prize winning biography, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Samuel Eliot Morison wrote that Columbus’s policies in the Caribbean led to “complete genocide” — and Morison was a writer who admired Columbus.

A woodcut by Theodor De Bry, in the 16th century, based on the writings of Bartolome de las Casas.

If Indigenous peoples’ lives mattered in our society, and if Black people’s lives mattered in our society, it would be inconceivable that we would honor the father of the slave trade with a national holiday. The fact that we have this holiday legitimates a curriculum that is contemptuous of the lives of peoples of color. Elementary school libraries still feature books like Follow the Dream: The Story of Christopher Columbus, by Peter Sis, which praise Columbus and say nothing of the lives destroyed by Spanish colonialism in the Americas.

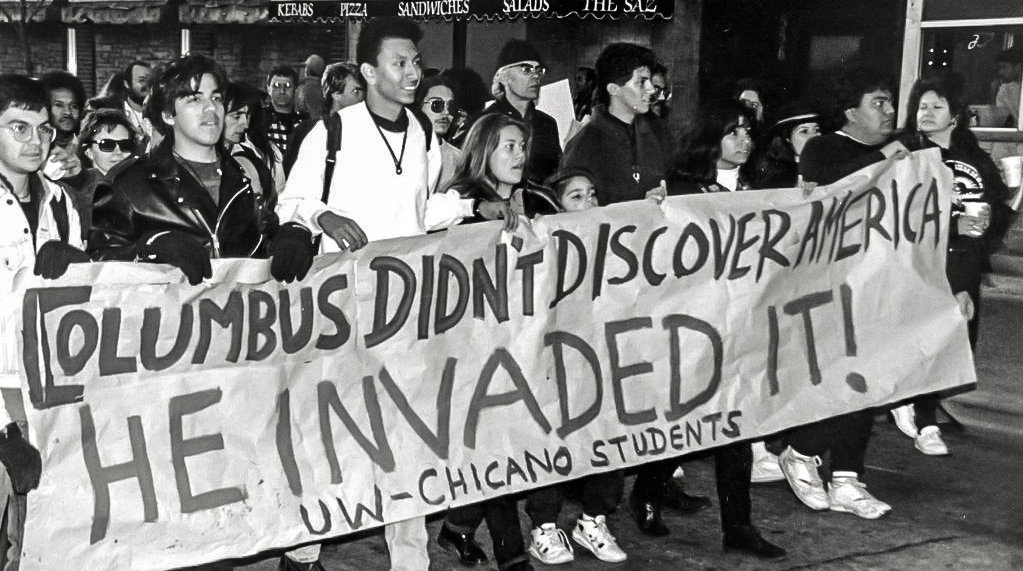

No doubt, the movement launched 25 years ago in the buildup to the Columbus Quincentenary has made huge strides in introducing a more truthful and critical history about the arrival of Europeans in the Americas. Teachers throughout the country put Columbus and the system of empire on trial, and write stories of the so-called discovery of America from the standpoint of the people who were here first.

But most textbooks still tip-toe around the truth. Houghton Mifflin’s United States History: Early Years attributes Taíno deaths to “epidemics,” and concludes its section on Columbus: “The Columbian Exchange benefited people all over the world.” The section’s only review question erases Taíno and African humanity: “How did the Columbian Exchange change the diet of Europeans?”

Peter Sis’ interpretation of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas in “Follow the Dream.”

Too often, even in 2015, the Columbus story is still young children’s first curricular introduction to the meeting of different ethnicities, different cultures, different nationalities. In school-based literature on Columbus, they see him plant the flag, and name and claim “San Salvador” for an empire thousands of miles away; they’re taught that white people have the right to rule over peoples of color, that stronger nations can bully weaker nations, and that the only voices they need to listen to throughout history are those of powerful white guys like Columbus. Is this said explicitly? No, it doesn’t have to be. It’s the silences that speak.

For example, here’s how Peter Sis describes the encounter in his widely used book: “On October 12, 1492, just after midday, Christopher Columbus landed on a beach of white coral, claimed the land for the King and Queen of Spain, knelt and gave thanks to God . . .” The Taínos on the beach who greet Columbus are nameless and voiceless. What else can children conclude but that their lives don’t matter?

Enough already. Especially now, when the Black Lives Matter movement prompts us to look deeply into each nook and cranny of social life to ask whether our practices affirm the worth of every human being, it’s time to rethink Columbus, and to abandon the holiday that celebrates his crimes.

More cities — and school districts — ought to follow the example of Berkeley, Minneapolis, and Seattle, which have scrapped Columbus Day in favor of Indigenous Peoples’ Day — a day to commemorate the resistance and resilience of Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas, and not just in a long-ago past, but today. Or what about studying and honoring the people Columbus enslaved and terrorized: the Taínos. Columbus said that they were gentle, generous, and intelligent, but how many students today even know the name Taíno, let alone know anything of who they were and how they lived?

In 2014, the Seattle City Council adopted a resolution to celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day, not Columbus Day. Source: Flickr/Vanessa.

Last year, Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant put it well when she explained Seattle’s decision to abandon Columbus Day: “Learning about the history of Columbus and transforming this day into a celebration of Indigenous people and a celebration of social justice . . . allows us to make a connection between this painful history and the ongoing marginalization, discrimination, and poverty that Indigenous communities face to this day.”

We don’t have to wait for the federal government to transform Columbus Day into something more decent. Just as the climate justice movement is doing with fossil fuels, we can organize our communities and our schools to divest from Columbus. And that would be something to celebrate.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Published on: Huffington Post | Common Dreams | AlterNet.

© 2015 The Zinn Education Project

Image Credits

- Columbus protest: UW-Madison Archives

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn