This car was brought to the Democratic Convention in Atlantic City to show the delegates and press how Mississippi Blacks were treated when they tried to register to vote. Source: Jo Freeman.

By Julian Hipkins III and Deborah Menkart

Mississippi sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer gripped the nation with her televised testimony of being forced from her home and brutally beaten (suffering permanent kidney damage) for attempting to exercise her constitutional right to vote.

“Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings?” she asked the credentials committee at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

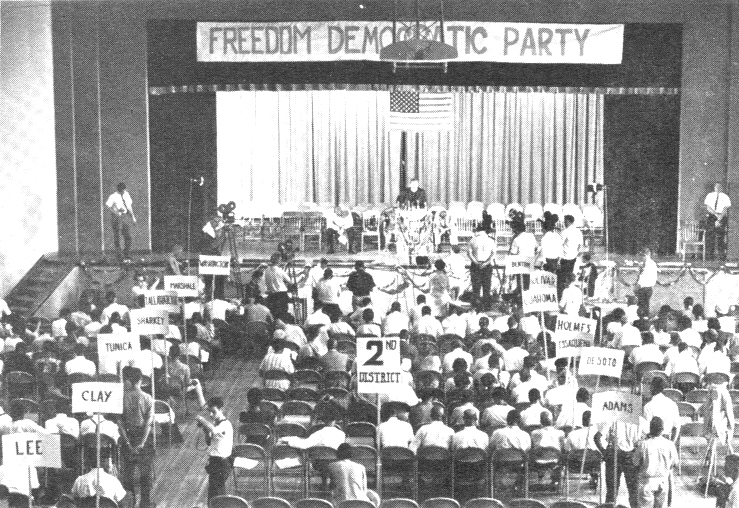

Hamer had arrived in Atlantic City on a bus from Mississippi with more than 60 sharecroppers, farmers, housewives, teachers, maids, deacons, ministers, factory workers, and small-business owners. Most were African American and many were women in the integrated delegation. They represented the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). The MFDP had followed all the rules to represent the state of Mississippi — registering members in public places, not making literacy a prerequisite for citizenship, holding open precinct meetings throughout the state, and selecting delegates at a statewide convention. Historian Howard Zinn, who saw the process firsthand, said the MFDP “made the political process seem healthy for the first time in the state’s history. It was probably as close to a grassroots political convention as this country has ever seen.”

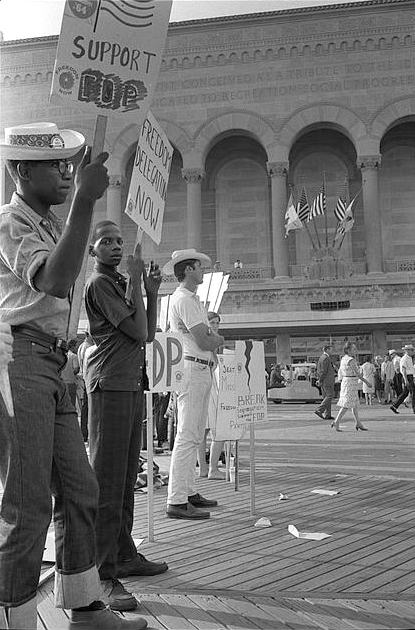

Supporters of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in front of the convention hall.

This delegation of grassroots citizens from behind the “cotton curtain” forced the Democratic Convention and the nation to grapple with the choice — would the all-white, top-down, good ol’ boy, “regular delegation” be seated, despite the fact that they had used state-sponsored terrorism and violated the Constitution to keep out blacks and also many poor whites? Or would the delegation that had followed the rules and opened its doors to all — regardless of race, gender, literacy, and employment — be selected to represent the state? Organizer and strategist Bob Moses explained, “We were challenging them to recognize the existence of a whole group of people — white and black and disenfranchised — who form the underclass of this country.”

This question of citizenship and political representation is as important today as it was then — yet the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party is not even mentioned in many major U.S. history textbooks. Vital lessons about the possibilities of grassroots democracy are lost to our next generation of voters. Historian Wesley Hogan explains, “Students in the 3rd and 4th grades learn about the ‘committees of correspondence’ during the Revolution and high schoolers learn about the Constitutional Convention debates of the 1780s. The MFDP was and is just as important a development for U.S. democratic practice as either of these foundational struggles. African Americans forced first the state of Mississippi, then the Democratic Party, and subsequently the nation as a whole to live out its uncashed promise of ‘one man, one vote.’”

Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker, August 6, 1964 at a Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party convening.

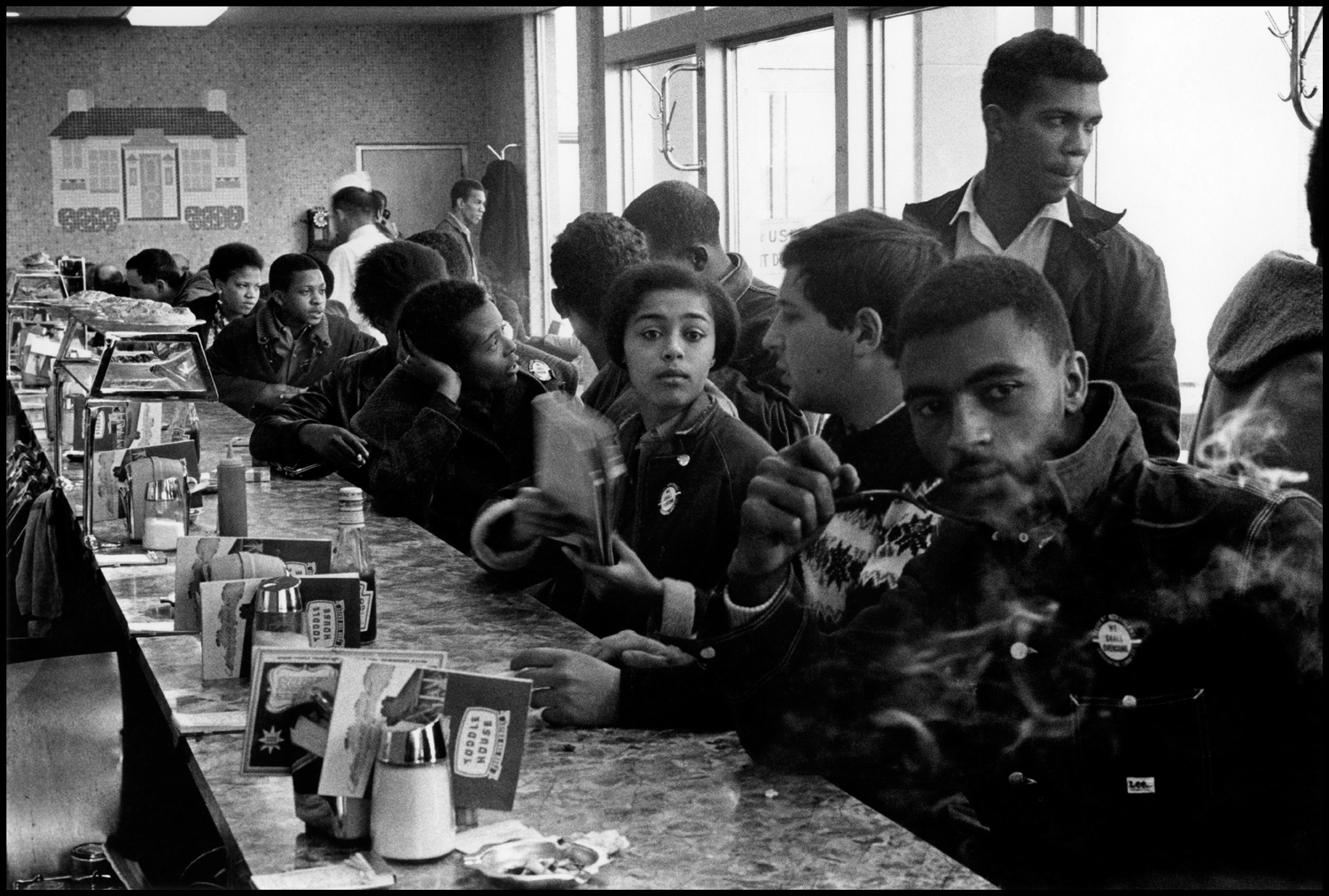

The process of the MFDP is equally as important as its outcome. Textbooks too often reduce the Civil Rights Movement to what SNCC veteran and journalist Charles E. Cobb Jr. describes as “hand-clapping, song-filled rallies for protest demonstrations and dynamic individual leaders using their powerful voices to inspire listening crowds. [Lost in that is] the crucial point that, in addition to challenging the white power structure, the movement also demanded that black people challenge themselves. [For example, the MFDP held] small meetings and workshops [that] became the spaces within the black community where people could stand up and speak, or in groups outline their concerns. In these meetings, they were taking the first step toward gaining control over their lives, and the decision-making that affected their lives, by making demands on themselves. Our meetings were conducted so that sharecroppers, farmers, and ordinary working people could participate.”

As educators faced with student cynicism in our “one dollar, one vote” electoral process today, we want students to learn from the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party about how to take on the Goliaths in politics. We realized that students should not just read articles, fill in worksheets, or answer end-of-chapter check-up questions, but instead participate themselves, facing the challenges and decisions of the MFDP delegates.

We co-wrote a role play where students take on the identity of MFDP delegates, credentials committee members, journalists, politicians, and others. They meet each other at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City. They hear the forceful testimony of Fannie Lou Hamer and learn that she scared President Lyndon B. Johnson, who hastily scheduled a press conference to distract the media. LBJ knew Hamer’s moral authority had the power to sway the nation in favor of the MFDP and he was determined to keep this largely African American delegation on the sidelines at “his” convention.

Aaron Henry, chair of the MDFP delegation, speaks before the Credentials Committee at the DNC.

They also learn that two of their classmates are FBI agents and that by feeding information to LBJ, the president has been able to threaten some of their supporters. The excitement, the strategic thinking, the outrage, and moral integrity of the MFDP infuse the room. Our experience with this activity and others is that students crave a history that allows them to see examples of small “d” democracy in action.

The students then grapple with the final “compromise” from LBJ: Two at-large delegates from the MFDP. All of the regular white Mississippi delegation, if loyal to the Democratic Party, will be seated with full privileges. They listen to the voices of national leaders, such as Bayard Rustin, who said, “When you enter the arena of politics, you’ve entered the arena of compromise.” Others, like Bob Moses, a key organizer of the Freedom Summer project in Mississippi, questioned the offer: “We were trying to bring morality into politics, not politics into our morality.” He also stressed that it was up to the MFDP delegates to make the decision themselves.

Most students vote to reject the compromise, as the MFDP did in 1964. They agree with Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer who said, “We didn’t come all this way for no two seats when all of us is tired.”

MFDP delegates demonstrate as President Lyndon Johnson is being nominated. Center is Victoria Gray from Hattiesburg, Miss.

Students are disappointed and angry that the MFDP was not seated. This is an opportunity to learn that victories are not always as immediate or tangible as a head count at a demonstration. Wesley Hogan highlights the longer-term impact: “The MFDP figured out how to ‘break the back of apartheid’ within the Southern Democratic Party at this convention, though the MFDP didn’t realize it at the time. There would never be another all-white delegation to the Democrats’ national convention.” The following year, the 1965 Voting Rights Act was passed. This pivotal legislation would not have been possible were it not for the efforts of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

In this day and age when elections are bought and sold by the 1 percent, the MFDP provides another lesson. As Hogan notes: “It is more important to stay accountable to your constituents than take home crumbs from the political table.”

Finally, the MFDP reveals an historic turning point when another outcome was possible. Stokely Carmichael said, “The Democratic Party leadership had a chance to reach out to embrace the future, and instead they reached back to try to preserve a shameful past.” What would our society be like today if the Democratic Party had taken the high ground? The MFDP invites students — and all the rest of us — to consider how we can create a political system that embraces a more just and truly democratic future.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Posted at: Huffington Post | Common Dreams.

© 2014 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Image credits:

- Bombed out car: Jo Freeman

- Supporters in front of convention hall: Library of Congress

- Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker: Johnson Publishing Company

- Aaron Henry speaking at the DNC: Library of Congress

- MDFP delegates demonstrating: George Ballis, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn