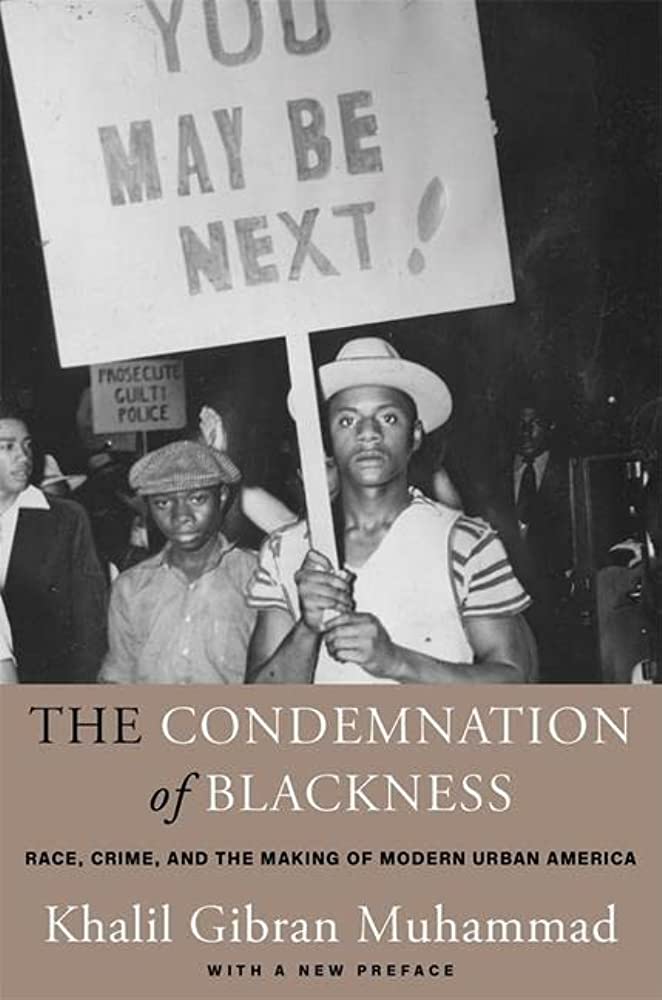

On January 8, 2024, historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad joined educators Jesse Hagopian and T. J. Whitaker to talk about his book, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, a history of the idea of Black criminality in the making of the modern United States.

This session was the latest in our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss upcoming sessions — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and the impact of the session:

I am delighted that today’s session was so intergenerational. I got the chance to connect with high school students in my breakout room and it was a refreshing reminder that the Black Freedom Struggle is not only being taught despite truth-teaching being criminalized, but also it is being learned and put into practice!

One of the most important things I learned today is that there are many brave teachers across the country who are helping their students understand the correlation between race and crime. I am so encouraged by this!

I appreciated hearing about the history of how data has been (mis)used to construct a narrative of Black criminality.

Thank you for breaking this down so clearly. You have given me stronger language to use in the classroom and beyond.

This session was so rich. One lesson is to constantly be wary of statistics and efforts to determine criminality. Another powerful lesson for me was the connection between Black education and Black criminality, as if there is causation. I am also thinking of Du Bois, who said that “an educated Black man is a dangerous Black man,” because there is an element of potential danger for education to empower change to the white supremacist status quo.

This was so enlightening. I will be at future classes. Thank you for all you do to bring the truth to educators.

Thank you for making me think, making me connect, and speaking the truth so boldly and clearly.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everybody to our class with Khalil Muhammad. My name is Jesse Hagopian, I work with the Zinn Education Project, and I’m an editor for Rethinking Schools. Some of you are joining us for the first time, and some of you have participated since we started. It’s just truly a gift to be able to share this time together with you all in virtual community.

And I want to let you know that today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change as part of our Teaching for Black Lives Campaign. We have members here from our Teaching for Black Lives study groups; if you’re in one of those groups, please add T4BL after your name on Zoom. I also wanted to let folks know that we at the Zinn Education Project offer free, downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have probably used for middle and high school students, and we also have an important report on Reconstruction that we hope you all will check out and think about how to use in your classrooms.

I am co-facilitating today’s class with high school teacher, Prentiss Charney Fellow, and great all around human being, T. J. Whitaker, who has been part of this series for a long time. T. J., thank you so much for agreeing to help with our session today. It’s good to have you with us. I am very excited to welcome historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad, professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School and author of The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. Formally, he was the director of a place that we hold very dear, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Thank you so much for being with us.

Khalil Gibran Muhammad: Thanks, Jesse, it’s a pleasure. Thanks, T. J. and all the great folks at the Zinn Education Project for doing what you do, for extending knowledge in every place that we deserve to be free.

Hagopian: No doubt. The work that you’ve been doing on the frontlines of this struggle to make the freedom to learn a reality has been an inspiration to me. I’m really excited for this conversation. The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, I think, is a history of the construction of this idea of Black criminality in the making of the United States, and think it reveals the influence of this pernicious myth that’s rooted in statistics on our society and our sense of self, really.

So, we wanted to start off by asking you about your perspective on how crime is defined. Because we know that when police killed Breonna Taylor as she slept, that was not deemed a crime. And we know that when the U.S. killed hundreds of thousands of people in Iraq, there were no generals or presidents who went to jail for that. That wasn’t a crime, either. Or the current U.S. funding of war crimes in Israel and Palestine is not a crime. But when someone steals food so they can eat, that’s a crime in our society. So, how do we make sense of what crime is in our society, and why associating Black people with crime has been such a persistent feature of American politics?

Muhammad: Well thanks, Jesse, that’s certainly the broad context that I think, trying to answer a question like this, makes sense, especially for people who are teaching our young people. Because as every educator knows, we start with simple concepts and then we complicate them as students mature. So what you teach in the primary grades is often a much simpler version than what you teach in the advanced grades.

Let’s start, essentially, with a crime in the most basic sense. Crime identifies a set of behaviors that violate some agreed upon set of norms that most people in the community agree to, whether they agree formally, whether they agree in the abstract through, say, a constitution or body of laws. Or say, often in the global South communities that are under-represented by law enforcement, where communities do just fine dealing with violations of community norms. They may or may not use such languages, but they do understand when someone has breached those norms. I think that’s the best way to start the conversation, because what it is predicated on is some agreed upon definition of a violation. And as we extend that definition to larger groups of people, as we introduce power, we begin to understand that who gets to decide what those rules are and what those norms are becomes much more complicated, and often an expression of political, economic, and cultural power.

One of the most revealing things about the United States, from its history in settler colonialism from the sixteenth and 17th century, is that by any definition of what we recognize in the 20th century as a set of international norms to protect against genocide, the United States was borne out of genocide, borne out of conquest, borne of the right to use violence as a means of land, acquisition, and dispossession, borne of the divine right to use the bodies of enslaved people. And so every child today gets taught that modern slavery is human trafficking, it’s a crime against humanity. But certainly for most of the history of the West these were not considered crimes against humanity.

And so, if we go from where you started Jesse, from the big context, and then we break it down to statutory law — that is, the municipal laws, state laws, and federal laws — then we recognize that the definitions of crime are borne of the imbalance of power, and often protecting private property against poor people, often protecting the wealthy against unlawful violation of their due process rights. One of the most striking things, if you’re an educator, is just to simply show the level of prosecutorial discretion afforded during the Trump administration. where people knowingly or knew that crimes were committed but weren’t sure they could win in court, in which case prosecutors often decline to move forward. Which doesn’t make any sense. To a commonsensical person, we know he broke the law. Prosecutors have evidence, but they don’t think they can win, and so the person goes free.

At the low end of the scale, or the deep end of the pool, as we often say, poor people — who may or may not be innocent — often have just the opposite form of punishment for so-called crimes. That is, the presumption of guilt means that because they’re poor and often of color, they will often lose in court. And so they plead guilty, again, for many things that can either be described as contextual. Meaning a person was poor, they shoplifted, or they even assaulted somebody, or even robbed somebody — many of which are violations even of community norms but don’t necessarily amount to the level of punishment that we often apportion in our society. So I think trying to be thoughtful. The story I tell is essentially that the label of criminality was attached to Black people at the end of slavery as a means of asserting control over their freedom. So this had nothing to do with crime, in most instances, and everything to do with Black people asserting freedom.

Hagopian: Oh, I just love how you broke that down. I can’t wait to have that conversation with students about what is crime, and get to use some of what you said to help spur their thinking.

T. J. Whitaker: if I could pick up where you left off, Dr. Muhammed, connecting your definition of crime to statistics. In The Condemnation of Blackness you write about how the 1890 census was the first to record the lives of Black people borne out of enslavement. You write about how that census was then used in the 1890s by the statistician Frederick Hoffman in his book, Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro. You say Race Traits was the first study to include a nationwide analysis of Black crime statistics, making arguably the most influential race and crime study of the first half of the 20th century. So, can you tell us about how the data that was compiled from the 1890 census was then used to create that narrative about Black criminality? What was Hoffman’s argument and how did he use the statistics to construct that narrative?

Muhammad: Sure, yeah, that’s a great question. And I know someone who doesn’t know this work is probably thinking like, what does the census and this have to do with the conversation about crime after the end of the Civil War? Well, it’s an origin story, and the good thing about this — for teaching purposes, from a pedagogical standpoint — is sometimes these ideas about defined crime live up here. And even in the way which I defined it, there’s a lot of big ideas to wrestle with in this story.

We actually have a singular individual who emerges in the late 19th century, a German immigrant. He comes to the United States in the 1880s, he’s unemployed, he’s ambitious, and he has a real knack for statistical analysis. He’s very observant, and one of the things that he observes is that the 1890 census reveals that the Black population is only 13% nationally, which, ironically enough, is about the same today. But it is 30% of the nation’s prisoners. And this statistical disparity — this overrepresentation, almost three times overrepresented in the nation’s prisons — becomes an argument in Hoffman’s seminal work called Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro, published in 1896, to essentially say this is the proof that Black people are a criminal race.

Now the lead up to that is fascinating, because, while he looks at the census data to make this claim, the underlying story is the story of power and contestation over Black freedom. Coming out of the end of slavery, Black people made their freedom dreams manifest in attempts to own property, to negotiate their own labor agreements, to build institutions, to take their role in governance, both in state legislative houses as well as in Congress. I know I’m telling you all this history that you all know very well, but putting it in context for the educators and students here this moment, when Black people grasp the reins of their citizenship is a fundamental threat to white Southerners, and increasingly becomes a source of unease and discomfort amongst Northerners. And in that moment, Southerners quickly latch onto the idea that we don’t have to put up with Black freedom. We can just pass a series of laws that criminalize their political activity, that criminalize their parenting, that criminalize their labor rights and right to challenge who they work for, and where they work in the conditions of labor they work under, and quickly from the 1860s to the 1870s, under the Black Codes, to then convict leasing into the 1880s. What happens to everyone? Listening is all of this, turning to the Southern criminal justice system, to police, to restrict Black freedom produces what? What does it produce?

Crime statistics. It produces arrest data, it produces the evidence of Black people going to prison or prison farms, or serving on convict leases. So, when the German immigrant shows up in 1884, looks at the 1890 census, which is one generation removed from slavery, he looks at the numbers and says, “The numbers speak for themselves. These people, relative to other struggling immigrant populations,” which happen to be Southern and Eastern Europeans at the time. He says, “They’re the worst of the bunch, and the statistics tell us that we should be suspicious of them, that we should surveil them, that we should restrict their freedom and movement because they are a threat to society.” That’s the basic argument. That’s the context. So we know, and his students, too, recognized that his argument was unfair because there was discrimination, there was racism, there was violence directed towards Black people. Black people were arrested literally for voting. They were arrested and prosecuted for defending themselves against violence. I could go down the list. The point is that a huge number of Black people, in that seminal moment, were innocent. Some were not.

And so, it’s important to establish that for those who were not innocent, because they lived under extreme economic and political repression and when they turned to either theft or violence, they were doing essentially what human beings have always done as forms of resistance — including the patriots who use violence, so-called, against the crown, Great Britain, to free themselves from the tyranny of that oppression. So, you put all that together and the contribution that Hoffman makes is to establish this argument on a national scale that becomes the dominant framing of understanding the disproportionate rate of crime by Black people. And it takes off everywhere. Northerners accept the argument, Southerners accept the argument. Big city, small city. I mean, it really spreads all over society, and the only people to resist this were civil rights leaders of the time. People like Du Bois or Ida B. Wells. We’ll talk about them again later. So, there was resistance. And there were a few allies resisting as well.

Hagopian: Yeah, I want to ask you about that resistance. Because I think Black intellectuals and activists really did develop a powerful critique of these crime statistics. I’d read about Ida B. Wells’ campaigns against lynching and I was fascinated by W. E. B. Du Bois’s work on Reconstruction. He had an important critique of standardized testing that I’ve read about, but I didn’t know until I read your book about their critiques of these crime statistics. Then also, later, by people like Anna J. Thompson. So I was hoping you could talk about these people, these Black intellectuals and activists, who really debunked this idea of Black criminality.

Muhammad: Yeah. So I’m hoping that Ida B. Wells, sometimes known as Ida B. Wells-Barnett, is increasingly becoming a household name and being taught more commonly in high school, especially in Chicago, where I’m from. There are more monuments having been built to her in the last few years, and there were always streets named for her in the Chicago of my childhood. So this Black woman starts her career as a journalist in Memphis, Tennessee, and she witnesses the killing of three friends, three Black friends, who own a grocery store. They are killed for the crime of their economic success. Literally, their business is so successful that it poses a threat to local business owners. They refuse to shut their business down, and in exchange for their success, they are killed in a triple lynching. She writes about it in her newspaper.

And for her commitment to speaking truth to power, her newspaper is burned to the ground. She leaves Memphis and goes to Philadelphia where she continues to speak about lynching. She’s so committed and passionate about speaking about mob violence and terror. We hear a lot about terror in the news these days. It literally is an uninterrupted campaign of anti-Black terror that is sweeping the South, of which she had been a direct witness. She takes this to the international court of public opinion and travels to the U.K. to tell these stories. What’s fascinating is, she’s one of the first Black antiracist activists of that era to do an in-depth statistical analysis of the reporting on lynchings.

What she wants to know is, she looks at 18 months of data covered in the Chicago Tribune, which was the dominant paper in Chicago at the time, kind of like the Washington Post does today, keeping track of police killings. So, she looks at this data over 18 months in 1892, and she discovers that the vast majority of lynchings that had been committed, against Black men in particular, were done in the name of protecting white women from rapists. But what she finds is that only in 31% of news coverage over an 18 month sample, were Black men even accused of rape that the majority of lynchings, the accusation that so-called justified the mob violence, were instances of a Black person killing a white person. And from her vantage point, Ida B. Wells, in the instance of self-defense. So she debunks this rape myth by looking at the statistics in white newspapers. She’s really the first person, and she publishes a book called Southern Horrors. She’s the first person to take on this myth of Black male criminality.

The second is W. E. B. Du Bois, who is a Harvard trained social scientist, and he writes a massive tome called The Philadelphia Negro, which at its heart is a way of understanding the social and environmental context in which a disproportionately poor population was overrepresented in crime statistics. What’s interesting about Du Bois is he did not consider himself an activist at the time. He considered himself a true social scientist. So he was unafraid to define Black people’s criminality in moral terms. He wasn’t proud that Black people were overrepresented in crimes of poverty and in crimes of violence, but he understood that poor people faced with certain constraints on participation in legal economies are one, likely out of survival to commit crimes of property. And two, because they cannot sue people when they are taken advantage of, they often have to use violence or the threat of violence to negotiate their own personal safety. He understood this, and so he wrote his book, which takes on Hoffman’s arguments. Du Bois is having an intellectual debate with Hoffman and actually calls him kind of a foreigner who doesn’t know what he’s talking about. It’s pretty fascinating, and there’s an article that we can share with you all later where you can see Du Bois taking on Hoffman.

So we fast forward from that point, in the 1890s — both of those books were published in the 1890s — to someone like Anna Thompson, who’s writing an investigative report for the Philadelphia Urban League in the 1920s, and she’s basically doing the same thing. She’s looking at the overrepresentation of arrest statistics in Philadelphia. We’re outside of the South, it’s past the period of the great migration, and she discovers that Black people are about 7% of the population of Philadelphia at the time. But they’re 25% of all arrests. And so people like Hoffman use such data to say, “See, they’re even criminals in a place like Philadelphia, where Black people have lots of opportunities, as compared to say, Birmingham, Alabama.”

But what Anna Thompson, a Black woman, discovered when she looked closely at the data — and this was true across multiple studies published in the 1920s — was that the vast majority of Black people were arrested for things that weren’t even criminal. It was disorderly conduct. People were considered trespassing on the steps of their own homes. They were picked up for considered vagrancy, and vagrancy was a very elastic crime that often attached to people who appeared out of work, which is essentially criminalizing poverty. Of those, 25% who were overrepresented in arrest statistics for the city were guilty of violent crime, or even things such as robbery or burglary. So when you put it all together, what you have here is decade after decade of the production of crime statistics — which are borne of Black people being over surveilled, subject to racist treatment, no recourse in court — and the accumulation of these disparities that are not read as evidence of racism, but disparities that are read as evidence of people who are degenerate, who have a crime problem, who are a dangerous race. And unfortunately, while Black people were able — like Du Bois and Ida B. Wells and Anna Thompson — to win some of these arguments, and were able to convince some of their white peers to change how they wrote about and explained the crime problem. Ultimately, Black people did not win that battle, and we carried forward the same logic and thinking right up to the present day.

Whitaker: So, we want to shift gears a little bit, and just look at the dichotomy in terms of how crime is looked at in two communities. We were fascinated to read in your book about how different European immigrant populations were racialized in the U.S., and then how their acceptance into whiteness transformed the narrative around structural causes of criminality in those communities. So, if you could talk about the way crime evolved into becoming evidence of the inequities that European immigrant communities were subjected to, whereas Black people or Black crime is explained as a result of personal failure, degenerate culture, biological inferiority, a narrative that really reminds some of us of the discussion that’s going on currently. So, can you touch on some of that?

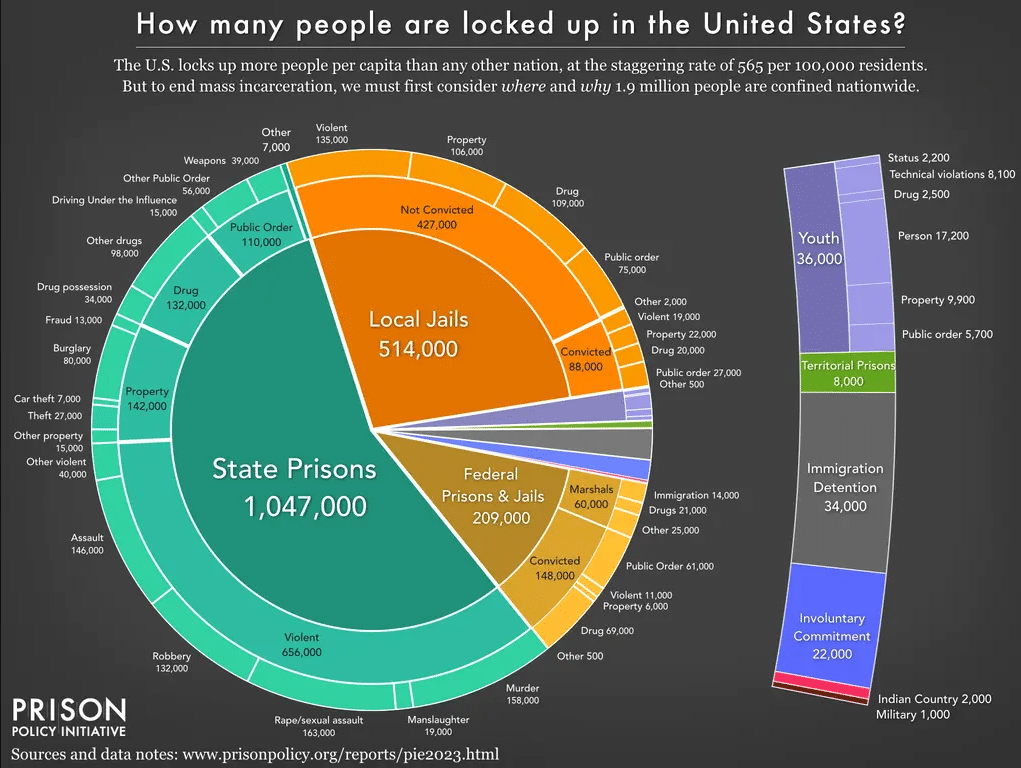

Muhammad: I actually think, T. J., that’s the best way to shorten the learning curve, or to flatten the learning curve, on this issue. We are currently living through a moment when most law enforcement and elected officials, and certainly the public health community, looks at crimes like heroin or methamphetamine use and abuse, and related crimes associated with the use of those drugs, as a public health crisis of addiction as compared to, even to this day, the criminalization of Black drug addiction. Heroin remains a problem in terms of how it is treated in the Black community alongside the crack epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s, which drove much of the problem of mass incarceration today.

Some of our political leaders would like us to believe that everyone’s more enlightened today. But if we were more enlightened today, we would have seen a massive reduction in the incarcerated population of people who were sentenced under the harsh drug war and drug laws of the 1980s and 1990s. But we have not seen that. We’ve seen a very small number of people who have been let out of prison, who were sentenced under those very racist and Draconian drug laws. So when we go back 120 years, literally 120 years, many people learn in history books that Southern and Eastern European immigrants — first the Irish, then the Italians — often, as the story goes, were subjected to tremendous nativist, xenophobic racism, and were subject to police brutality.

For example, the first blue-ribbon study of police brutality in the country took place in 1894 in New York City, and mostly the victims of police brutality were Irish. They were victimized by Anglo-Americans — they called them “Old Stock Americans” — and they just beat the Irish with impunity, for looking the wrong way, for walking down the wrong street, for not showing proper deference, for voting for the wrong candidate, you name it. So most American students, even to this day, learn something about the racism that European immigrants face, including Jews in the early 20th century. What they don’t learn is that at that precise moment progressives and liberals step in to save them, to change the laws, to build settlement houses, to focus on police reform.

The fact that I mentioned the first blue-ribbon commission on police brutality is in the interest of helping the Irish is a perfect case in point. There’s an entire set of public policies that come on the books in the 1890s, 1900s, 19-teens really, right on through the New Deal era, to essentially help these people be less subjected to racism as xenophobia. There is an immigration law, for example, that passed in 1924 that does restrict many of these populations to very small numbers, which is kind of the end of the era of xenophobia. But over the twenty years before that, a lot of social scientists who were self-defined liberals and progressives tried to help them, and they did a pretty good job of it.

The most important thing they did is they redefined their crime, not as crimes of nationality, of an innate culture. They defined them as crimes of environmental stigma. They invite crimes of inequality, as we would understand it today. Hoffman himself, when he’s writing about Black people, is simultaneously writing about high rates of crime committed in white immigrant communities, and says that it is a problem of inequality in society. He says, “The health of the people must come before the wealth of the people, and that’s why we have so much crime in white communities.” The hypocrisy was breathtaking.

Jane Addams similarly made contradictory statements. She talked about prostitution experience among immigrant girls in Chicago. She talked about high rates of juvenile delinquency. She talked about crimes of violence committed between Polish and Irish kids, shooting each other with weapons. She said, “This is a problem that repeats itself every day in the daily newspapers.” And her solution was not personal responsibility. Her solution was not to denigrate the cultures of these people. Her solution was a massive campaign of public recreation, a massive campaign to help these people. She actually says, “We cannot expect the fathers and mothers who have immigrated from faraway places to fix this problem. This is our problem to fix.” And so from that moment through the rest of the 20th century, white criminality increasingly became a symptom of a social problem, whereas Black criminality increasingly became a symptom of Black people’s problem.

Hagopian: Incredible research you did on that. And it’s so revelatory about how crime gets discussed in the news today as well. I hope everyone will read that. I want to ask one more question before we move to breakout rooms. One of the most fascinating parts of the book for me was to read about how you develop this argument that Black education has been associated with criminality. You write, “Calls for greater African American access to public education, for example, were challenged by statistical arguments that education turned Black people into criminals.” I hear echoes of this argument when, for instance, Trump blamed Howard Zinn’s writing for inciting the riots during the 2020 uprising. But talk about this history of tying Black education to Black criminality.

Muhammad: I had not thought about this, Jesse. This is why it’s so important for us to be in community. What you said about Trump tying Howard Zinn to the riots, I mean . . . Some of you know from watching the news that the hearings on December 5th, where the university presidents opened with remarks that people who have been teaching this radical ideology on college campuses, that Virginia Fox described as antiracism or Critical Race Theory, are responsible for the antisemitism on campus. That’s a way of literally criminalizing the teaching of these topics that we’re talking about today, to say very little of the 20-plus states that had passed laws to literally criminalize the right to learn, to read, to speak on these issues.

So of the many surprising things looking at the origin story that I tell in The Condemnation of Blackness, I could not have predicted that I would come upon a debate that starts really around the late 1890s. In the same moment as Hoffman is working, where there’s a census report, and this is fascinating. The census report shows that the disproportionate arrest rates among Blacks compared to whites is higher in northern cities than it is in southern cities. So if you are thinking with a racist logic you would say Black people are even more criminal in the north than they are in the south, because the disparity was higher in northern cities than it was in southern cities. And so someone propagated the idea that because the arrest rates were even higher in the north — like Chicago, Philadelphia, New York — and that Black people had more educational opportunities in Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia as compared to the south, that the association, which they considered causation, was that the more access to education Black people got, the more criminal they became.

Now none of this makes sense. The math doesn’t add up. But guess what? We live in a time right now in 2024, where things don’t have to make sense. Facts don’t actually have to matter. Logic is relevant or irrelevant. It just depends. And that’s exactly what happened then. Now though, what’s fascinating is, the way I tell the story is, I tell it through the debate, not because I’m imposing my presentist view on the past. I tell it because Black people call these people out on their BS. So, Du Bois calls them out and says, “This doesn’t make any sense.” A Black mathematician at Howard University calls these people out and says, “This is just racist.” In fact, the best counter argument was from this Black sociologist named Kelly Miller. It’s just fascinating, and it’s math. It’s looking at racism through the lens of math. He says, “Okay, fine.” If it’s true that, for example, in Massachusetts, Black people are five times overrepresented in the arrest statistics, and in Massachusetts Black people have far more options for schooling than they do in Mississippi. This is the argument, hypothetically. This is what Kelly Miller says. He says, “Then why is it the case that in Massachusetts white men are ten times overrepresented in arrest statistics as compared to white men in Mississippi?” And it’s kind of like a drop the mic moment. Because if the logic applies, then you have a problem. You would essentially say it’s even more the case that going to school in Massachusetts drives white men to more crime than compared to in the South. And so Kelly Miller says the reason this doesn’t make sense is because it didn’t make sense in the first instance.

This wasn’t just a debate between intellectuals and census data. It turns out that by the early 1900s, major spokespersons like Theodore Roosevelt, who was then President, would go around the country and give graduation speeches at Black colleges. He did it at Hampton in 1905. He did it at Tuskegee in 1906, and in his remarks which were covered in the New York Times, he said such things as

Today, you graduates of Hampton are continuing a tradition of law-abiding Black men, because at this college something like 6,000 graduates have come from here, but only two have proven to be criminals. So keep up the good work, and make sure that you are against the criminals in your own community more than any other thing, because that’s the worst thing for you people.

It’s astonishing because what it turned out to be was that there was a tradition, a new tradition then, of counting the alumni of Black colleges in terms of their crime statistics. And you could kind of judge whether the school was doing a good job or a bad job based on the crime rates. Now, the thing that I say in the book is that this wasn’t happening at predominantly white colleges and universities. But if you applied the same logic at Harvard University, where I work today, over its almost 400 year history, and you applied an economic analysis to the amount of crime or the cost of crime to society, you would have a number in the billions for the amount of white collar criminality coming out of Harvard University and the scale of damage done to people’s lives, and the justification for every form of exploitation.

For example, what number do you put on the thousands of Indigenous remains that are still on the property of Harvard University today, or the stolen bodies that were used for scientific research? So, the crime numbers game was always an expression of the power of people to oppress you by defining your community as criminal. That’s why Black scholars like Kelly Miller pointed out the statistical fallacies that were being circulated at the time, and that were showing up in commencement speeches and all sorts of things, similar to the way that these lies about Black criminality continue to circulate on social media right now.

Hagopian: Thanks for breaking that all down. . . . All right. So let’s get back into the conversation, y’all. I think T. J. wants to start us off with a question.

Whitaker: I think our students will appreciate this one, too, because we were watching the interviews earlier today. But those in power are very afraid, very scared, of all this history we’ve been talking about. There have increasingly been bans on teaching honestly about race, gender, sexuality, and capitalism in the United States. You said in a Democracy Now! interview, quote, “What Florida Governor DeSantis is doing is actually shaping national education standards,” and made the case that Florida is a laboratory of fascism at this point. More recently you said that Claudine Gay’s resignation as president of Harvard after the December 5th House Committee hearings was the next step in what is now a 3-year long campaign to destroy this country’s capacity to address its past and its present. Can you say more about what you think is at stake in the struggle for Black education and teaching about true history?

Muhammad: If we applied the same standard of national security to Soviet Russia all of us would be essentially arrested for political activity in this conversation. I mean that when our own political leaders today, like Ron Desantis and others, talk about American freedom, and they contrast it with Russia and the former Soviet Union, they are describing a situation where freedom of speech, freedom of the press, our political rights to due process, are all held up in contrast to those totalitarian societies where people did not have those freedoms. And so Ron DeSantis is constantly beating his chest about American freedom. Nikki Haley answered a question recently in Iowa where she was asked “What role did slavery play in the Civil War?” And I’m not even sure she actually was asked; it wasn’t a leading question. It was like “what caused the Civil War,” and she talked about the struggle over government and government’s right to abridge people’s freedoms and the need for capitalism to thrive.

So we are living through a time in this country which is not the first time that fascism has created political movements, the most obvious of which actually coincided with the growth of what we call fascism today, in the late 1920s and early 1930s in Italy and Germany. There was also fascist movement here, and even fascism as it connected with anti-semitism was a homegrown phenomenon in parts of this country going back to earlier periods of time. There was a fascinating book I reviewed in the New York Times by Sam Friedman this past summer about Hubert Humphrey. It talks a lot about Minneapolis as kind of the capital of anti-semitism in the early 20th century. So, what we see in Florida has been innovating how much fascism you can actually get away with in electoral politics. How much can you push the limit on criminalizing speech, books, the right to protest and the freedom of expression, personal autonomy, and actually continue to be elected, to have a political mandate? Because everyone who studies fascism knows that fascists are always democratically elected to then destroy democracy. So Ron DeSantis, in his innovative efforts to destroy the ability of Florida educators to teach an honest and accurate American history, started to experiment around the ability to control not just speech and learning, coming on the hills of pushing back against gains made against voter suppression in that state. I don’t want to go too far down the rabbit hole, but I just want to make a simple point that the right to vote and the right to protest came before the restrictions on the right to vote, and restrictions on the right to protest in Florida came before restrictions on the right to learn these histories, or the right to care for the needs of non gender conforming youth.

So when we get to the AP story of the college board capitulating to Florida’s pressure by describing whole bodies of knowledge as illegitimate to the state of Florida, we saw early on the potential for one state. in this case Florida, to impact a national curriculum. Because the AP curriculum is used as a standard curriculum across every state, and every student takes one of those classes — in this case, it would be the future African American studies class. He then extended his efforts to restrict the autonomy of a local college called New College, where he replaced the entire board with people supportive of his agenda, which is a fascist agenda in the state of Florida. Most recently, they’ve removed one of the Gen. Ed. requirements for the entire state system in Florida, because sociology apparently is radical Marxist teaching, because anything that focuses on inequalities is now being rendered a crime against the state of Florida. I’m mentioning and emphasizing Florida because they showed us exactly what they intended to do, they’ve done exactly what they’ve intended to do, and they’ve become a model for other states like Texas, Arkansas, Iowa, and Oklahoma. And of course, most recently, those states also have passed legislation restricting public funding for DEI programs in higher education.

So, fast forward to the Congressional hearing, where most people have focused only on the challenge to whether the college presidents should have answered that they would punish students for being critical of Israel. I’m not going to take the bait because no one on any campuses called for genocide against Jews. But using such language as “Freedom from the River to the Sea” or “Intifada” are appropriate terms of debate as to what they mean to different people, which is precisely what all the people who believe in so-called “freedom” in America — they should have a right to say what you want to say, including that Black people are criminals. So anyway, I digress.

That testimony opened, not with setting the table for understanding what is the appropriate line between academic freedom and hate speech, it opened explicitly with calling out the radical ideology of Critical Race Theory and antiracism and intersectionality as the primary drivers of anti-semitism on college campuses. And if you watch the five hours of testimony, about half of it was focused on equity and DI as the real problem. Now, just to close on this point, two presidents have since resigned since December 5th, and in the wake of Claudine Gay’s resignation last week, a forced resignation, the chairwoman of that committee has promised to continue to go after Harvard, because, as she said, this is not about an individual, this is about an institution.

At least Stefanik has called Harvard “institutional rot and corruption” and Virginia Fox described the problem as “woke faculty and partisan administrators.” So what started in the public arena of K through 12, and extended to higher education and Florida public college and universities, has now extended to private universities. And a billionaire donor class are using their influence against private elite institutions by withholding their dollars to rip the heart out of academic freedom and the autonomy of teachers like myself to teach these histories, where one day it is not inconceivable that people like me would be in jeopardy of either losing my job or violating some laws that these people have put on the books.

Hagopian: Thank you for breaking that down it. It truly is chilling to think about the fact that Florida has made the official state curriculum say that slavery was a quote “personal benefit to Black people.” I really appreciate how you look at this laboratory for fascism. But you don’t limit it to Florida. I think that the CRT tracking project out of UCLA has now shown that almost half of the students in the American public school system are subjected to one of these laws that criminalize teaching the truth about race or gender or sexuality. So we are in a struggle.

I think we talked before the session started that that looks a lot like McCarthyism, that it looks a lot like some of the most severe repression in the U.S. history. So, thank you for breaking that down for us. I wanted to ask you a question about the settlement houses. This was a fascinating part of the book that I didn’t know anything about before I read Condemnation. You look at the case of settlement houses in Philadelphia and how they were positioned on the frontlines of strategies for crime prevention during the Progressive era. I was hoping you could talk about how this Progressive era initiative was used to address the roots of crime for European immigrants, and how that same analysis wasn’t extended to Black people?

Muhammad: It’s another part of the archival record. Again, I want to be mindful both of time, since we’re starting to come to an end, but also to teachers. You are often limited in your ability to teach certain topics by the dependence upon primary sources rather than secondary sources. I mean, one of the big problems with the so-called AP African American Studies curriculum was the debate over what was a primary source versus secondary source. And one of the things that’s very powerful is to look at settlement house records, some of which I profile extensively in the book where, on the one hand, when it comes to European immigrants, they literally define the problem of community violence, meaning gun violence. Actual gun violence, not hypothetical gun violence, not like the Martin Scorsese version of Italians back in the day. Gun violence, actual gun violence that was occurring within white immigrant populations. They talk about drug use. They talk about crimes of poverty, etc. They show single parenting by immigrant women having too many babies. It’s all there in the settlement houses.

Their solutions, though, are to actually help to eliminate the social causes of these problems, to give these folks the economic opportunity that they need, and to protect them from the retrograde racist forces that often prey upon them. When you look at the same settlement houses that operate in communities that often have Black residents in them, Black people are literally excluded from them, they are segregated from them, they cannot have access to the same resources. Hull house, which is the most famous of them, the one that is most studied and most remembered for Jane Addams and her influence. Jane Addams was a wonderfully influential and generous, compassionate person. But there were limits to her compassion and her generosity. She did not extend that compassion and generosity fully to Black people in her own community, and as a result, Black people were kept from some of the same remedies and access to opportunities that were extended to these immigrant populations.

Hagopian: I think another fascinating historical part of the book is your look at the 1918 race riot in Philly and then the Red Summer 1919 race riots across the country. I was hoping you could comment on what the underlying causes of this racial violence were, and then how policing in the U.S. was radically altered, how it was shaped by this era?

Muhammad: It’s a really rich period during the Great Migration era, and I hope that all the educators here, since there’s so many, enjoy that period in U.S. history like I do. It’s a period when Black people kind of take their agency back, when they vote they vote with their feet by leaving the Jim Crow South, and they begin to move to Northern cities. This is the period when jazz leaves New Orleans and becomes, eventually, a global phenomenon. It’s just a rich period. And of course the Harlem Renaissance may be the most studied part of the Great Migration period. Well, there are two things that are underappreciated from that period that I write about. One is the level of violence that Black migrants experience in all of these Northern cities. I mean, these are pogroms against the Black community, and largely, the underlying cause is that Black people are beginning to demand access to housing and jobs in ways that threaten the monopoly on such things that white immigrant populations have.

And what’s interesting is the Great Migration helps to force greater homogeneity amongst immigrant populations that had often previously been separated. So there was Little Italy, there was the area where the Irish had a kind of lock on things, and Polish Catholics. And there was the Jewish Ghetto, and all of this because of the increasing presence of Black folks to integrate migration. Many of those white immigrant populations start to band together, to keep their communities all white, and to keep their workplaces all white. And so part of forging a communal whiteness is also the collective violence directed towards Black migrants that occurs in this period. And that’s what those race riots were about.

The second thing that’s under-appreciated is the role of policing in those race riots. There’s no period — no period exists ever at any point in the past — when Black people got due process in policing, when their interests were protected and served. By and large, poor people have been very poorly served by police in general, including poor white people.

But what emerges in this period is that policing in the North begins to take on some of the same work and function that lynch mobs do in the South, and they’re not necessarily the primary distributors of violence towards the Black community. But they are often there when it happens. Sometimes they participate, and oftentimes they either disarm Black people from having the capacity to defend themselves or they arrest them. So you can have entire instances where the Black community is literally being massacred, and the police show up and arrest the Black people.

And what comes out of this period? I mean, it’s fascinating. The best study ever done on this is a book called The Negro in Chicago. It’s a riot report published in 1922, and you can teach it. It’s huge. There’s lots of material there. But one of the things that comes out of it — and you have to kind of brace yourself for this — in the study they interview white criminal justice officials, police officers, chiefs. They talk to court officials, judges, you name it. And basically, these people admit that there’s wide scale prejudice against Black people, and that Black people are subjected to unlawful scrutiny. That Black people are arrested with no evidence. They’re sent to jail for things that wouldn’t be a crime if a white person committed them. All of this is admitted to and the solution that they come up with in the 1920s is unconscious bias training.

Whitaker: I mean, that’s amazing. It’s remarkable.

Muhammad: So 100 years ago, when white criminal justice officials were honest about what was going on in a place like Chicago, they came up with the same solutions offered to us in the era of Black Lives Matter protests.

Whitaker: So we are stuck on stupid.

Muhammad: I just don’t know what other way to describe it, because time and time again those recommendations led to no action. They went nowhere. And you have reports in the 1930s and 1940s, the current commissioner report in the 1960s. By the time we get to the 1990s, the federal government is producing reports all over the place, in almost every major city. So, stuck on stupid.

Hagopian: I hear you. What an incredible conversation.

Muhammad: But I have to answer the question, though, Jesse, because nobody answered, so I’ll take it. I’ll take it very quickly. The answer to the question about why Black man and white man were overrepresented in Massachusetts as compared to Mississippi, is because Massachusetts had a much larger criminal justice bureaucracy. You are much more likely to be arrested, charged, and convicted of a crime in Massachusetts, simply by virtue of the density of population and the age of that system, than in Mississippi, which was more like a frontier society. That’s the answer.

Hagopian: Wow! So much wisdom being dropped tonight. And I can see so many applications of your research for educators, for language arts teachers, math teachers talking, using the research you did on statistics. And of course, history and social studies teachers. There’s just such a rich body of work that I hope everybody will dig into and get your book and use it in class. So, I want to thank you so much for your time this evening. What a wonderful conversation! And I look forward to being in the struggle with you for honest education in the future.

Muhammad: Thank you, Jesse. It’s been a real pleasure to be here, and thanks so much for the very thoughtful questions. And T. J., too, thanks for bringing students.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audiogram

In this audiogram, Khalil Gibran Muhammad discusses Reconstruction, the 1890 census, and the misleading statistical narrative of Black criminality.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

|

The Color Line by Bill Bigelow Who Killed Reconstruction? A Trial Role Play by Adam Sanchez (Rethinking Schools) Reconstructing the South: What Really Happened by Mimi Eisen and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca The Heroes We Need Today: Teaching About the Radical Ida B. Wells by Matt Reed (Rethinking Schools) Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca “Riots,” Racism, and the Police: Students Explore a Century of Police Conduct and Racial Violence by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca; see more classroom resources in the Teach the History of Policing collection.

|

Books

| In addition to The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, the following books were referenced.

Chokehold: Policing Black Men by Paul Butler (The New Press) I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction by Kidada E. Williams (Bloomsbury Publishing) The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander (The New Press) No More Police: A Case for Abolition by Mariame Kaba and Andrea Ritchie (New Press) Teaching for Black Lives edited by Dyan Watson, Jesse Hagopian, Wayne Au (Rethinking Schools) W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America by the W. E. B. Du Bois Center (Princeton Architectural Press) |

Articles

|

A Call for Anti-Bias Education by Erica Licht and Khalil Gibran Muhammad at Learning for Justice. Interviews on Democracy Now!:

Khalil Gibran Muhammad On Why Educating Kids On Race In America Is More Important Than Ever (Time Magazine video interview) Five Ways Textbooks Lie About Reconstruction by Mimi Eisen (an addendum to the Zinn Education Project report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle) Remembering Red Summer — Which Textbooks Seem Eager to Forget by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (from the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series) More than McCarthyism: The Attack on Activism Students Don’t Learn About from Their Textbooks by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (from the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series) |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

Participant Reflections

With more than 270 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 31% K–12 teachers, 20% teacher educators, and 11% K–12 students.

Teaching for Black Lives study group coordinator Linnet Early (in St. Louis, Missouri) spoke briefly about the impact of being a part of a Teaching for Black Lives study group. She said, “The biggest impact the group had was allowing participants to start seeing the inequities that exist in their own sphere of influence.”

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Honestly, there was so much that I didn’t know and am just learning. It is so humbling to realize that I did not realize how much the economic gains of Black people were masked as Black criminality, and all of the history to support that.

To be mindful of how data is used and how we use data to look at our communities today.

There were so many important things that I learned today. One that resonates with me is the intentional history of the criminalization of Black people and the impact that it still has today on our right to education, work, quality of life, and how to “read between the lines” to recognize it.

The through-line of crime classification, statistics, and racism.

The use of statistics to shape the myths. I also appreciated the breakdown of the dichotomy of standards between European immigrants and Black Americans.

That we as Black people create our own stories, so we should not rely on often distorted statistics to impact the way we see ourselves.

The most important fact I learned today was that Ida B. Well-Barnett produced the first in-depth statistical analysis of lynching in the United States by gathering 18 months of data and analyzing newspaper articles in 1892. The second most important idea I learned today is that fascists are typically democratically elected and then move to destroy democracy.

One astonishing story I learned was how the three Black business owners were killed simply for being successful.

I didn’t know about the racism in the settlement houses barring Blacks from services.

This was a great session! This lesson connects with a recent documentary about misdemeanors and how they are used to criminalize Black, Brown, and poor people. It also reminded me about the information in the documentary 13th.

I really appreciated learning about the research and contributions to addressing the issues of criminalization from Ida B. Wells, Ana Thompson, and W. E. B. Du Bois.

What will you do with what you learned?

Foster in students the habit and skill of digging deep and not taking numbers at face value. Helping students understand that though numbers may not lie, people use numbers to tell the story they want to tell.

I plan to use this with the Teaching for Black Lives study group I facilitate. I also use Dr. Muhammad’s work to accompany Ida B. Wells as examples of how we challenge the neutrality and objectivity of science and statistics.

I will be bringing this history back to my fifth graders as they already know that the truth about United States history is being kept from us.

I am teaching Reconstruction this semester and will be reading more about Ida B. Wells.

I will use this information to help students interrogate the mayor of Philadelphia’s platform to address crime.

I have known some of this information but will need to keep educating myself so that I can share more with my colleagues and as a conversation topic in our Teaching for Black Lives study group. I continue to be blown away by how much of this information I was never taught!! It makes me more resolute to bring it to our district and to our students. I love the ideas of picture books and primary sources for young children, too.

I plan to start a book group with my grandchildren and their friends.

I now feel primed to engage more critically and mindfully with statistics in my courses, and through my research. I am struck by Dr. Muhammad’s research and how he traced the ways that statics have been historically used as evidence of Black criminality instead of evidence of white supremacist anti-Blackness. When I become a postsecondary teacher, I really want to prioritize the use of primary sources, particularly sources that use statistics to formulate and justify their claims.

Encourage student journalists to feature Ida B. Wells among their profiles of influential journalists during Black History and Women’s History months.

I teach very young students (6-8 year olds), but plan on expanding our conversation of race and gender being social constructs to include crime as a social construct.

I will try to make lesson plans incorporating the history of criminalization and abolitionist ideas into K–5 Art.

This is a good reminder to me to continue being aware and proactive in looking for opportunities to educate people on the impact that systemic racism has historically had, and continues to have. I am also going to take a trip to the library and pick up some of the books referenced in the discussion.

Presenters

Khalil Gibran Muhammad is the Ford Foundation Professor of History, Race and Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School. He directs the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project and is the former director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a division of the New York Public Library. His writing and scholarship have been featured in national print and broadcast media outlets, such as the New Yorker, Washington Post, The Nation, National Public Radio, PBS Newshour, Moyers and Company, MSNBC, and the New York Times.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

T. J. Whitaker is a high school language arts teacher in the New Jersey South Orange-Maplewood School District, and a Prentiss Charney Fellow.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn