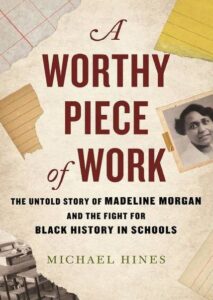

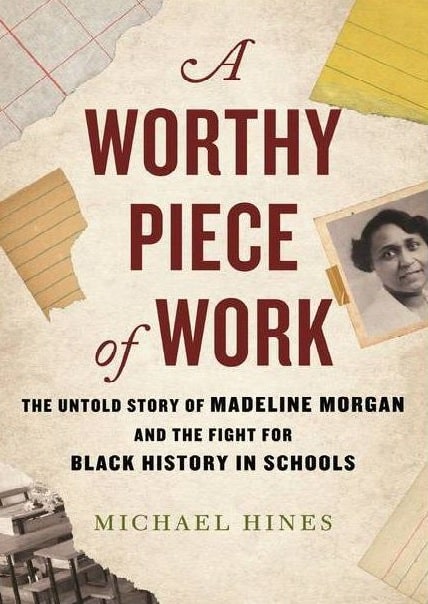

On November 13, 2023, historian Michael Hines joined Cierra Kaler-Jones, Rethinking Schools executive director, and Jesse Hagopian, Rethinking Schools editor and high school teacher, to discuss his book, A Worthy Piece of Work: The Untold Story of Madeline Morgan and the Fight for Black History in Schools.

This session was the latest in our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss upcoming sessions — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and the impact of the session:

I learned about Madeline Morgan, a leader and visionary that laid the groundwork for educators today who fight to teach truth and Black history in schools. It’s inspiring to hear her story and the impact she made on the students who finally saw themselves reflected in the curriculum.

There are so many stories that are submerged within history. It’s important that we understand the contributions of Black teachers in preserving and reshaping the narrative around Black contributions to society.

Teachers have power! This work cannot be supplemental; it needs to be at the forefront.

Black women educators like Madeline Morgan deserve their just due! The struggle didn’t just begin. There have been amazing educators, especially Black women, who have made a huge impact by teaching Black children about themselves.

I absolutely want to read Dr. Hines’ book and learn more about what Madeline Morgan did with her curriculum. I think the lessons will be helpful for today’s classroom and what we need to know to use a similar curriculum today.

Madeline Morgan, the O. G. of activists in educational reform!! I can’t wait to read more about her.

I continue to be amazed with the extent of information that I am still learning. I’m looking forward to reading A Worthy Piece of Work as I continue to build depth in my understanding of American history as a whole — in all of its good, bad, and ugly parts.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everyone to our class this evening with Michael Hines. My name is Jesse Hogopian. I work with the Zinn Education Project, and I’m an editor for Rethinking Schools. I’m joined by my colleague and comrade Cierra Kaler-Jones, who is also the executive director of Rethinking Schools and a member of the Zinn Education Project leadership team.

Some of you are joining us for the first time, and some have participated since we launched this series. We were just reflecting that it was over three years ago, maybe three and a half years ago now, that we started this incredible series. It’s a gift to be able to share this time together with you all and be in virtual community together.

Today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by both Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change as part of our Teaching for Black Lives campaign. We have members here today from our Teaching for Black Lives study groups that have been organized all across the country. So, if you’re in one of those groups, please add T4BL after your name. It’s great to see everybody introducing themselves in the chat. Let us know where you’re coming from; that would be great. And I just wanted to let folks know that the Zinn Education Project offers downloadable free lessons, history lessons that many of you have used for middle and high school classrooms on our website, including lessons on a report that we issued about Reconstruction. Cierra, let me turn it over to you.

Cierra Kaler-Jones (she/her): Thanks, Jesse. Everyone, it’s so good to be in this virtual space with you. Before we begin our conversation we want to find out who is in the room with us and go through our plans for our time together. We’re posting a quick poll to find out how many teachers, educators, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, and others are in the room with us. Many of you are in multiple roles, so just pick your primary one. If for some reason there are tech challenges and you can’t put your role in the poll, go ahead and put it in the chat box.

Introduce yourself. We’re so excited that you’re here. and here are a few notes about our format today. ASL Interpretation is provided by Krystal Butler and Tierra Carter. At the end of the session we ask for your feedback. Trust me, we read every word, and that is where you will request your PD credit. The full recording and the resources listed in the chat will be sent to you in about a week.

Halfway through we have it so that you can meet each other and actually talk in small groups to share your thoughts with one another, and then return for more Q&A with our speaker. Aso, Tweet what you’re learning; share it with your community and tag ZinnEdProject. Okay, let’s see the results of the poll. It looks like we have 36% K–12 teachers — so appreciative of you all, much solidarity and lots of love. We have 3% K–12 students — so welcome to the students, welcome to the young folks. We’re so glad that you’re here. Two percent family members to students, 28% teacher educators in the house coming in strong, 7% historians, and 2% librarians. Thank you all so, so much for joining us. We know this will be a robust and exciting dialogue.

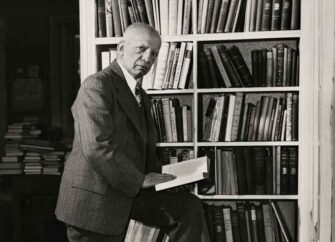

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Yeah, and I’m so happy to welcome historian Michael Hines, whose work focuses on educational activism of Black teachers and students and communities through the progressive era of the 1890s to the 1940s. He’s the author of a wonderful book called, A Worthy Piece of Work: The untold Story of Madeline Morgan and the Fight for Black History in Schools. Thank you so much for being with us here tonight.

Michael Hines (he/him): Thank you so much for the invite. It’s lovely to be here.

Cierra Kaler-Jones (she/her): What a fantastic book. I know I learned so much, and there were so many pieces of Madeline Morgan’s story that I had never learned before. It also just resonated deeply with me, so thank you so much for this incredible text. I’m excited to dive in. So, what encouraged and inspired you to highlight Madeline Morgan’s story? How did you first learn about her?

Michael Hines (he/him): I first came to Madeline Morgan during the process of writing my dissertation. I got my PhD in 2017 from Loyola University, Chicago, and this book really grew out of that work. When I started looking for a dissertation topic, I had a couple of things in front of mind.

First, I wanted to study something local. Chicago has this incredibly rich heritage when it comes to black history. You can think about the contributions the city’s made to Black music, art, literature. I wanted to find some of the educational roots of some of that. Then, second, I wanted to tell a story that looked at Black education before Brown v. Board. There’s a lot of incredible scholarship that’s been written on those tragedies and triumphs of the post-Brown world, of the desegregation era school integration.

But my interest as a historian was a little bit earlier, to the early twentieth century, late nineteenth centuries. With those interests in place, I started looking for a topic, and just really listening, because in Chicago we have this really great tradition of Black historians. People like Timuel Black, who just passed at the age of 102 in 2021. Just these amazing historians with this deep knowledge of Chicago’s Black history.

I was fortunate enough to sit with a man named Christopher Robert Reed. He’s a professor at Roosevelt University, who wrote some of the first histories of Black Chicago. I really heard Madeline Morgan’s name for the first time sitting in his office just trying to keep up with the stories he was telling. He started talking about this teacher [Morgan], and I thought to myself, this can’t be possible. She’s doing Black history work in the 1940s. This is before culturally sustaining pedagogy. This is before culturally relevant teaching. This is before multiculturalism. This is before Black studies and multicultural studies. It’s before school integration. So that interested me. And that question of how did that happen really sort of drove my dissertation, and what became the book.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Yeah. I’m so glad you wrote this book. I realized the huge gap in my understanding of the struggle for Black education when I read it. I’d read stuff about Woodson and then stuff about the McCarthy era attacking Black studies. But there’s that gap in between there that I really didn’t know much about, so I really appreciated that. I was hoping you could give us a biographical sketch of Madeline Morgan, her early life, her education, and her organizational experiences that helped equip her with the skills that she would go on to use to become a champion for teaching for Black lives in her own day.

Michael Hines (he/him): I think Madeline Morgan, first and foremost, she’s a child of the great migration. She’s born in Chicago. But her father, John Henry Robinson, is a Southern migrant from West Virginia. Her mother, Stella May Dixon, is what Chicagoans called an “old settler,” which is the term for Black folks who can trace their families back to the nineteenth century. She grows up on the southside of Chicago, where a majority of the new migrants in the Great Migration land, in this area that’s known as the Black Belt. But during this period it’s getting renamed by Black folks themselves. They’re giving it the name Bronzeville, which is what it’s known as today. I think it’s really important, that ability for self-determination and self-fashioning, that we’re seeing grow in this period, on the southside of Chicago and in Bronzeville.

So she grows up seeing Black folks telling their own stories, whether that’s through the Black press, like the Chicago Defender, The Chicago Bee. Whether it’s through literature, I mean, there’s Langston Hughes coming through the city, Gwendolyn Brooks, Richard Wright. Whether it’s through cultural institutions, you could think about the George Cleveland Hall Branch of the Chicago Public Libraries. The Chicago Defender had this quote, referring to Black Chicagoans that said they make their own wit, their own music, they form their own views, they live their own lives, they do not constitute the fringe of white society. They are the nucleus of another society.

So, she’s growing up in that really rich tradition. At the same time, she’s going through formal systems of schooling where those stories are completely left out. When she goes to high school at Inglewood High school, which back then was predominantly Irish, she’s getting no Black history there. When she goes to the Chicago Normal College to learn how to become a teacher — this ostensibly progressive institution where she trains — she has teachers tell her that they’ve never heard of a contribution to American history being made by a Black person. When she goes to Northwestern, where she gets her masters degree, it’s the same thing. I think it’s really the tension between those two things: the stories that she knows are there, and then these structures that are telling her that we’ve never heard of this, that this doesn’t exist. That really started to drive her to think about these things in a new way.

Cierra Kaler-Jones (she/her): Wow! That’s so powerful. I love how you’re lifting up self-determination and the power of telling our own stories in our own words, and I love that Madeline Morgan really grew up in the spirit of that, and that then permeated and transitioned into her work and her teaching. You write, “white supremacy and anti-Black racism were deeply embedded in the curriculum of America’s schools in the early twentieth century, particularly in history and social studies.” So, can you give us examples of how schools and textbooks portrayed Black history, starting from the Reconstruction era through the early twentieth century?

Michael Hines (he/him): Sure. First of all, it’s important to set the context right when we’re talking about race, portrayals of race, and textbooks in the early twentieth century. They’re really reflecting, and they’re reinforcing the racism that’s just prevalent in the broader society. So white supremacy and anti-Blackness were endemic to society in the early twentieth century. From science we can think about social Darwinism and the rise of the Eugenics movement. It’s in popular literature, right? The first Tarzan book came out in 1912. We could think about early films, like the Birth of a Nation, which premiered in 1915.

It’s everywhere. It’s down to children’s songs and nursery rhymes. I have a two and a half year old who just started singing “10 Little Monkeys Jumping on the Bed,” and I was like, Oh, God!, because I know where that song originated from, and I know it was 10 little negroes, except the word wasn’t negroes. So it was everywhere. It was very, very prevalent. It was in the water.

And then supporting all of that and reinforcing all of that is the official knowledge that’s portrayed in schools. Black people are being characterized as lazy, as unintelligent, as violent, as predatory, as lascivious. And all of those images help to sort of undergird oppression, whether it’s oppression in the past, like slavery, or whether it’s ongoing oppression, like lynching and segregation.

It was very interesting to do the research for this book because I had to do a lot of reading in very old textbooks. I pulled a couple of examples. The first is a description of slavery from Daniel Beeby’s America’s Roots in the Past, which is in 1927. He says,

On the tobacco plantations of Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, the slaves were usually treated kindly. The climate was healthful and the labor of growing tobacco was easy. The work was so simple that it was well suited to unskilled workers. Even when an overseer was employed to direct the slaves, the work was more or less under the master’s observation, and he usually lived on his plantation year round. In winter the slaves’ life was easy. Their work consisted of clearing a piece of land, cutting wood for the fireplace in the master’s mansion, and caring for the livestock.

So, I mean, those are the sort of portrayals. A second one from Ruth and Willis Mason West, The Story of Our Country, which was in the Chicago schools in 1935. They called the Ku Klux Klan “a secret society who dressed like ghosts in masks and long white robes, [and] rode around at night warning the terrified negroes to behave themselves and to let government affairs alone.” So, these are the descriptions that were just par for the course throughout the period that we’re talking about.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Wow! I mean, it hurts my heart. And what is even more painful is to see some of those types of betrayals coming back in our schools. Like in Florida, where, now, official state curriculum says that slavery was a “personal benefit.” I mean, that mind boggling ignorance can only be understood when you know the history of U.S. curriculum, that this is not the first time. Everything you write about, they’ve developed these types of ideas for a long time.

Michael Hines (he/him): Right? Echoes of past curricula. Yeah.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): No doubt. You write about the early history of this Black History Movement and you say that “Morgan’s efforts in the Chicago schools were part of a larger wave of scholarship and activism aimed at the preservation and promotion of Black history. In the early twentieth century an intellectual and social project that historian Pero G. Dagbovie terms the quote ‘early Black History movement’.” So, I was hoping you could talk about some of the highlights of that movement to teach Black history even before Madeline Morgan’s time.

Michael Hines (he/him): I think that this movement goes back. I mean, Black educators have been teaching Black history for as long as Black people have been in this country. But formally, in the schools, I think we can trace the movement back to the work of people like Edward A. Johnson in the late nineteenth century who writes A School History of the Negro Race in America in 1891 or 1892. People like Leila Amos Pendleton, a teacher in D.C. who wrote A Narrative of the Negro in 1912. So, this is a movement that’s been ongoing, and I think what’s different about the 1920s to 1940s, that sort of solidifies it into this movement, is that it becomes really far reaching, really deep, more extensive, better organized.

A name that we’ve already said tonight, I think, is responsible for that. It is in large part the result of Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. Woodson puts together this machine, and it’s still going. It’s still going strong, this machine for the documentation and the dissemination of Black history. And the Association launches academic journals. The Journal of Negro History is holding annual meetings; it’s putting scholarship out there. They’re working in the schools through the negro history bulletin. And of course, the effort that most people are familiar with, which is the Negro History Week movement that becomes Black History Month that we know today.

So that’s really the engine that’s driving this movement during Madeline Morgan’s time. She’s a part of the Association and she really leans on the Association. I think it’s important to recognize that while Carter G. Woodson was the head of the movement, the people who are out in the trenches doing the work day-to-day were these Black teachers, the majority of whom were Black women, who are really carrying this and interpreting it and giving it to kids and to communities.

Cierra Kaler-Jones (she/her): I love that shout out to the Black women teachers, and I just appreciate you for lifting up that and lifting up the everyday, ordinary people that do the organizing, that are part of the struggle, and that are leading the struggle in so many different local contexts. I want to talk a little bit about the intercultural movement, this intercultural movement that got going in education in the run up to World War II, which you talk about in the book. It was really fascinating to us. So, can you explain how World War II helped to create the conditions that led to the intercultural movement?

Michael Hines (he/him): So, by the 1930s, I think the early Black History Movement has grown. It’s expanded, but it’s still very much contained within segregated Black schools. What changes, I think in the late 1930s, early 1940s is that there’s another movement called Intercultural Education that provided this window for Black teachers to bring some of their thinking to bear and into the mainstream of American education. So, the Intercultural Education Movement — it’s also called the Tolerance Education Movement — really begins post-World War I, and then really gets going in the lead up to World War II. It’s concerned mostly with bringing together the sons and daughters of mostly white immigrants — Germans, Irish, Italians, Poles — into this united American whole. And as World War II is looming on the horizon and the threat of fascism is there, educators start picking up on this need for interculturalism in the schools.

And what Black teachers I think immediately recognize is that there’s an opportunity here. America is trying to portray itself as the beacon of democracy, equality, inclusivity and Black teachers are going, “Okay, we can use that same rhetoric, and we can turn it to argue for the importance of Black history as part of this broader American story.” They’re basically calling out the hypocrisy of what’s going on, and I think that happens a lot during the second World War — whether you want to talk about the first March on Washington Movement with A. Philip Randolph, whether you want to talk about the movement to desegregate the military, you could look at civil rights and nursing in war work. There are so many. I think that the Civil Rights Movement during the 1940s really lays the groundwork for what’s going to follow in the 1950s. It’s no surprise that school integration became this issue in the early 1950s because this groundwork had been laid in the 1930s and 1940s. So she’s really taking advantage of that.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Yeah, no doubt. I love how Morgan saw this opening, like, “Oh, you all want to talk about different cultures, but you don’t want to include Black people? That’s not going to work. So, let me open up some space here and we’re going to include Black people in the many cultures that make up this country.” And she went farther to actually create a curriculum that educators in Chicago could use to teach Black History, I think she called it the Supplementary Units for the course of instruction in social studies. So I was hoping you could talk about how she launched this movement and what was in that curriculum, and some of the struggles she had to go through to get it implemented.

Michael Hines (he/him): So, what Morgan does is really recognize that there’s this interest convergence. And I say that really pointedly, because I can talk about this more later, but interest convergence being one of the underlying principles of Critical Race Theory. But there’s this interest convergence between white policy makers at the district level — who are looking to shore up patriotism — and then Black educators who are looking for justice and representation. She develops this proposal for a Black history curriculum and it really takes every part of the existing curriculum and adds material to it. So if the students are studying ancient history, then she has material on Dahomey and other African kingdoms. If they’re studying explorers, then she has material on Esteban [de Dorantes] or Matthew Henson or Pedro Alonso [Niño].

But there’s more than just additional material. It’s something that’s written from a different perspective. So, looking at her units on slavery, they’re the complete opposite of this whitewashed version that existed before her. She’s including descriptions of the Middle Passage; she’s including descriptions of the violence that underlay the slave system; she’s describing resistance to slavery in the form of slave revolts and uprisings. So there’s this very different approach, a very different perspective that informs what she’s doing that comes from this tradition of this early Black History Movement. It’s really a counter-narrative to what’s going on in the official curriculum. So I think that’s the important thing to get, that it’s really cutting against the grain.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Right on. Yeah, I could see that. To follow up on that, I wanted to ask you a little bit more about how widely these Supplementary Units were adopted by educators. How were they received by teachers and students? How widely were they implemented?

Michael Hines (he/him): So, she succeeds in getting the city of Chicago to adopt the Supplementary Units in 1942, and that means that it’s used officially in about 353 schools in the Chicago area. But the question of how these units get used is really interesting for me as a historian and as a former K–12 teacher and current teacher at the college level because there’s always this difference between the curriculum that’s intended and the curriculum that’s enacted. There’s always a difference between what gets mandated and what teachers actually teach. So it’s difficult to know precisely how faithfully teachers use this curriculum. I don’t want to act like this curriculum comes in and magically upends white supremacy in the Chicago schools. It doesn’t do that. I’m sure that a lot of white teachers simply closed their doors and continued teaching whatever they wanted to teach without incorporating it.

But even with that, there’s a lot of evidence about the reception in Chicago, and outside of it. We have records of Black students. One of the fun parts of writing this book was hearing the voices of Black students from the archives saying things like, “Since I have studied negro history, every good word about negroes, and good thing they do, makes me feel swell. Just at one time we were not allowed to do nothing but work night and day, and now we are doing things just as important as anybody else.” That was this girl named Sandra Clark, who was in the seventh grade back then. Of course, that’s a pseudonym because I had to make up names for everybody.

Then we have white teachers and students who are giving the same kinds of reactions. I start the fifth chapter of the book with a story from a teacher named Grace Markwell who is in Brookfield, right outside of Chicago, and she reads her students this story about John Matt Slager and the shoe blasting machine, and her students, their minds are blown by the fact that there are Black inventors. Then they’re even more blown away when she tells them that a Black woman wrote this story about a Black inventor. So her fifth graders eventually beg her and beg her and beg her, and she lets them write a letter — which I put in the book — asking Madeline Morgan to come to their school and talk to them. We know those stories and we know a little bit about the national and international reception that her work gets. I mean, thousands of people — Black and white teachers, administrators, parents, soldiers fighting in the Second World War — are sending her letters requesting copies of these units. So I think her work is widely a success, but it’s always difficult to see exactly the parameters of how far she got.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Wow! It’s great to see the kind of progress she was able to make in that time. It’s a shame that her curriculum was only an addendum to the regular course rather than the core curriculum. And I think that’s a struggle we’re still in today, to make ethnic studies a graduation requirement or part of the core curriculum rather than just an elective or an add-on.

So this history just is empowering to me to hear that this struggle has happened before and we can continue in that legacy. So thanks for sharing those stories.

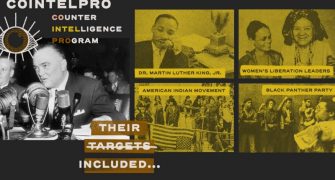

Cierra Kaler-Jones (she/her): Thanks. Yes, I love that. And I love that you’re also just really lifting up the power and how profound this curriculum was for so many people, and how that gets lost in history textbooks. So, can you talk about some of the obstacles to the implementation of the Supplementary Units into the Chicago Public Schools and the eventual end of the intercultural movement? What was the role of McCarthyism and the Red Scare in ending it? And just as a quick note, we have a lesson to teach about McCarthyism because it’s either missing or misrepresented in most textbooks, and we see those same McCarthyism-era tactics and chilling effects on teachers today. So, can you give us a little bit of that historical context?

Michael Hines (he/him): I think one of the major obstacles to her movement into the Supplementary Units, as I mentioned a little bit earlier, is that many teachers, especially white teachers in 1940s Chicago, were simply not ready to teach this material. No matter what was mandated, they weren’t going to do it, and some who were willing to do it were under-prepare. They had never been taught this material before themselves.

As we’re speaking about echoes of today, we can talk about teacher training and equipping teachers to be able to have these types of discussions. In terms of what actually spells the end of her curricular experiment though, I think it’s that the convergence of interest between white policy makers and Black educators that sort of held up during the war years begins to fade after 1945. We have Black soldiers and white soldiers coming back home to Chicago, and almost immediately starting this new war with each other. The late 1940s is this period of hidden violence in the city of Chicago, where you have all of these small-scale race riots because Blacks and whites are fighting for housing; they’re fighting for jobs; they’re fighting for space in public parks; they’re fighting for schools.

There’s this really violent white backlash to the fact that Black folks have made some headway during the war years. The mayor at the time gets ousted because he’s too friendly to the Black community. The superintendent at the time has his house firebombed because he’s trying to end a transfer system that allowed white parents to get out of schools and flee schools if the schools became too Black. Then, like you said, on the national level we’re seeing the switch from fighting fascism to fighting communism. So anyone who’s deemed to be a little too far left is liable to be targeted, and in that context, I don’t think a project like Madeline Morgan’s was able to thrive really.

[Breakout rooms]

Cierra Kaler-Jones (she/her): Hello, everyone welcome back. I hope that you had rich discussions. We’d love to hear what you discussed in your breakout session, so please share in the chat. Shout out your group, share highlights from your discussion. We’d love to hear from you. Before we return back to the conversation, I want to remind you that we have some more sessions just like this one coming up. So sign up now, if you haven’t already, for the sessions with Khalil Gibran Muhammad in conversation with Jesse Hagopian and T. J. Whitaker on the Condemnation of Blackness: Lies We’re Told About Crime.

As another announcement, one of our speakers from last year, Matthew Delmont, is donating 1,500 copies of his book, Half American, to teachers. Please see the link to request your copy in the chat. And as another giveaway, Seven Stories Press is giving away copies of the Spanish Edition of the new YA edition of A Young People’s History of the United States. Also see the link in the chat.

And as another note, please, please, please donate to the Zinn Education Project so that we can keep this work going. A former student of Howard Zinn’s, who is now a lawyer for whistleblowers, Dave Colapinto, will double all donations from now until Giving Tuesday, up to $15,000. Much appreciation to Dave for his support, and to all of you for continuing to help us as we fight back against these attacks on education.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): One way you can support teachers in bringing this history to the classroom is with our Teaching for Black Lives study groups that we have all across the country. We have more than a hundred of these study groups just this year, and you can see some of their locations on the map. And many members and leaders of these groups are in the session with us here today. Two of those coordinators are here: Dr. Candace Cofield and LaShelle Ferguson will share a few words about the impact of having a Teaching for Black Lives study group. So, Dr. Cofield, thanks for joining us. We appreciate you being here. I just wanted to ask you where you are based and about how many people participated in your group.

Dr. Cofield (she/her): Hi, all. Yes, I’m based in Hayward, California. That’s in the Bay area in Northern California. I’m in a T4BL class and we have about 22 members. The cool thing is, it’s not just teachers: we also have librarians, para-educators, and district leaders.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Oh, right on. And same question for you, LaShelle.

LaShelle Ferguson: Our school district is located in Prince George’s County, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C. Our group was small, about 10 members. It consisted mostly of middle and high school teachers and instructional coaches. But we do have on our social justice committee people who are our association’s board members that join us from time to time.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Excellent. I was hoping you could both share one story about how your experience in the study group really deepened your ability to teach for Black lives, or how it’s helping you shift the curriculum and teach outside of the textbook about Black history.

Dr. Cofield (she/her): I’ll say our group is really like an affinity space for all those who have voluntarily joined. They want to know more about not only what anti-Blackness looks like, but strategies to interrupt it. So the book helps us, it gives those supplemental resources that helps them not only understand it — because we also use Black culture as a way to build community — but specifically for our elementary school teachers, we’re looking at the curriculum and seeing how can we update what we have, because it’s pretty problematic to be honest. When it comes to Black history, it’s incomplete or, worse, inaccurate.

So, we use the study group to work together to see what we can take from the book and then use some of the other things that we know through our instructional leadership work to build a resource set for our teachers. So, here’s some lessons you can use to supplement what you have or completely replace it. It’s really built our capacity to, like I said, know what anti-Blackness looks like, and have strategies to interrupt it.

LaShelle Ferguson: For us in our county, it made us realize and focus more on the varied Black groups that we have. Black people are not monolithic, all the same, and people assume that. So, for example, in our county, we have African Americans, Afro Latinos, Africans, Caribbeans, mixed race people. So we realize that although we have a common thread, there’s significant cultural differences that people can often overlook. We realized, even in our curriculum, we don’t always cover different authors, different things of that nature, and that’s something that we need to work on. But also, including just because you assume, oftentimes, you may assume that someone is one race or an ethnicity, and they’re actually not. We’ve had experiences in our county where I have a coworker, let’s say she’s Afro-Latino, and people will say to her, “Oh, you’re Black,” and that’s negating the person’s cultural contributions and how they can basically enrich the school system.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Thank you both so much for sharing about your study group. I know you’ve inspired other folks on this call to think about participating in these groups, and I’m excited to see them continue to grow, especially in the face of these attacks on antiracist teaching. It’s really exciting to see you all being on the frontlines of this struggle. So, thanks for sharing your story with us. Well, welcome back Dr. Hines, we appreciate you being here with us. Did you enjoy the breakout group?

Michael Hines (he/him): I did. I got to sit in on a conversation. It was awesome. Thanks. And I saw your note in the chat about teaching in PG County at Bladensburg High School.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): That was the first school I ever taught at. So shout out to Prince George’s. I first started teaching in Washington, D.C. in Anacostia, right on the PG County line.

Michael Hines (he/him): That’s where I am now. So, we’re all connected. We’ll have to talk about Friendship Public Charter Schools; I taught for them for a couple of years in Anacostia.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): No doubt. Well, we had a couple more questions for you before we let you go. This book is just so rich, and there’s so, so many lessons to dig into. But I really appreciated something that you wrote in the introduction, and that I wanted to follow up on. You said, “a few Black women in the early twentieth century gained access to the kinds of credentials often associated with historical scholarship.” And you said that Black women acted as “historians without a portfolio.” So, I was wondering if you could say more about that, and why we don’t know, and why most students aren’t taught about these incredible figures like Madeline Morgan.

Michael Hines (he/him): The phrase “historians without portfolio” is from a scholar named Pero Dagbovie, who’s a historian of the early Black history movement. Like you were saying, it means that there are these generations of women before the mid-twentieth century who are doing all of this incredible work, this historical work, but are going unrecognized because they don’t have the PhDs, the graduate degrees, the offices on college campuses, and the status symbols that are associated with “professional historians.” So I think there are a lot of reasons that Madeline Morgan’s story is overlooked.

But I think a lot of it is the intersections of her identity. First, she’s a Black person in America. Second, she’s a Black woman in America. And then third, which I think is really important for this story, is she’s a classroom educator. So on the first side, we know that too often the historical narratives that we tell are still centered around what historians call great man history. We know that even that impacts Black historians. Even in the historiography of the Black Freedom Struggle, there’s this tendency to search out charismatic male leaders, individual charismatic male leaders, and center those stories. Whether it’s [Martin Luther] King or whether it’s Malcolm [X] or whether it’s Huey [P. Newton] or whomever. Then the people who don’t fit within that paradigm, whether it’s because of their gender, whether it’s because of their sexuality, whether it’s for other reasons, they don’t get the attention that they deserve.

I’m thinking right now about pioneers like Pauli Murray or Bayard Rustin, who are so critical to the movement, who are just now getting their due Then, in the history of the Black educational struggle, it means that we often center men like W. E. B. Du Bois, Carter G. Woodson, [and] Booker T. Washington. Those are the names that grab the most headlines and the most attention, even though it’s these thousands of Black women who are out here for the most part enacting those visions and creating their own visions. But they get left out.

Then, lastly, tied to that for Morgan is the fact that she’s a classroom teacher. And that’s a group that often still gets overlooked in our conversations about who has power, who are historical actors when it comes to education. I taught education policy for several years at Loyola University, Chicago while I was doing my graduate training, and I would start the semester off by asking my students — and these are all teachers and teacher candidates in the Teacher Ed program — I would ask them who makes education policy? Who affects change in schools? And they would tell me everyone but teachers; I almost had to drag the word teachers out of them. They would say nonprofits and government agencies and politicians and lawmakers and parents, and way down at the bottom of the list, even for them, was teachers. So I think that the stories of classroom teachers being centered is something that needs to happen more in the histories that we tell to incoming educators [and] to educators who are already out in the field, because it really changes the dynamic.

Cierra Kaler-Jones (she/her): Yes, yes, yes to all of that. I’m just loving how you’re lifting up the power of classroom teachers and the knowledge that they hold and continue to pour, not only into the curriculum and the pedagogy, but also the policy, the activism, the organizing that we can learn so much from classroom teachers. You also made me think about this quote from Monique Couvson. She said, “Black women, they know what they know, and they know that they know it.” And that sticks with me, particularly as you’re lifting up the power and the intersections of that experience that then lends them to a type of knowledge.

One thing that you also wrote, you said, “her reliance and Madeline Morgan’s reliance on scholarly communities outside of the boundaries of the school system, including local history, clubs, libraries, sororities, and civil rights groups, highlights the robust networks of support and sustenance that remain, although in different forms, in the present.” That makes me think about the Teaching for Black Lives study groups. We just heard from two facilitators, two leaders. There’s many leaders on the call, and thinking about the Zinn Education Project and Rethinking Schools, educators and Black Lives Matter at School educators that I’m in community with, D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice. Shout out to all of these groups of folks that I get to learn with outside of the academic space, and all of the teachers that I get to learn from their pedagogy. So, can you talk about the networks of support that Morgan leaned into, and how did that shape her activism and her teaching?

Michael Hines (he/him): I think you’re spot on. One of the the big takeaways from this project for me was the power of these networks of teachers that are outside of the formal system. In the 1920s and 1930s, when Madeline was coming up, it was Black teachers’ associations, it was very powerfully Black sororities and fraternities. It was the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, the NAACP, the Urban League. It was women’s clubs like the NACW and the NCNW. So you have these layers and layers and layers of organizing on top of one another that she can draw from. And I’m really interested in what that looks like today. You’ve named some of the ways that that’s still out there. Like Lee Patel says, study and struggle are always being intertwined. So, there are these spaces that are still existing where people are doing the work of studying, the hard work of studying, and it’s informing the struggle.

Out here in the Bay Area where I am now, I think of things like the Oakland Black Teacher Project. When I was in Chicago it was about the Surge Institute, which is this amazing network of Black and Brown educators. Then, to hear you talk about the study groups through the Zinn Ed Project, and and some of the programs in D.C., that’s just one of the reasons that I was really happy to be here, because this is the sort of thing that is continuing that legacy and continuing to build those networks of support.

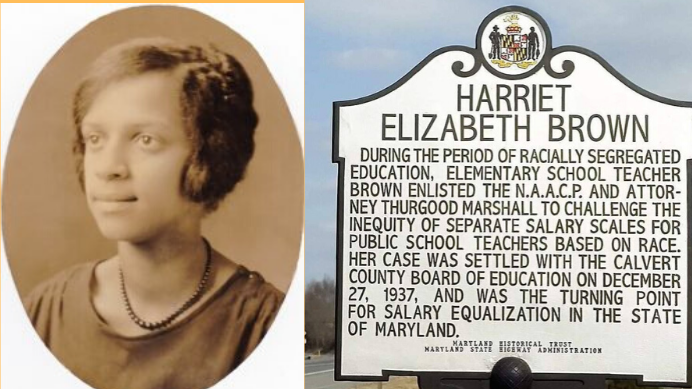

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Right on. Are there other teachers like Madeline that we should know about? I mean, if you think of other ones later, we can always add them to the email we send to teachers, but if there’s some off the top [of your head] that we should begin to look into, I’d be curious.

Michael Hines (he/him): So many teachers need their due and need their stories written. When I was doing this archival work in Chicago, going back to the networks, I was sort of mapping out who Madeline was in conversation with, who are her mentors, who are her associates, who is she running with? And that’s everybody from the Bridge Club at the church where she plays on Sundays, up to formal organizations. So I ran into just an amazing group of women. You talk about Maudelle Bousfield, who’s the first Black principal in the Chicago Public Schools, who’s really like an older sister to Madeline. Or Anita Cockrell, who’s the head of the Phi Delta Kappa sorority, the chapter that Madeleine is in.

Then this whole scholarship is just starting to take off but there’s a whole unexplored world of Black librarians and archivists that still need their stories told as well. There’s women like Vivian Harsh and Charlemae Rollins. Vivian Harsh was the head librarian at the George Cleveland Hall Branch of the Chicago Public Library. Charlemae Rollins was the children’s librarian. They both made this library in Chicago this hub and this bastion for Black history. It’s where Madeline goes to do a lot of the research for the curriculum that she writes. The idea now that’s being called liberation archives, who are the archives and librarians and archivists that are creating these liberation archives that are then fueling the wider movement. Giving those women their due, I think, is really important. So, shout outs to the librarians! Then nationally, there are women like Jane Dabney Shackelford, Constance Ridley Heslip, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. I could go on. But these are all women that need to be explored and need to have their stories told too. They’re all part of the same movement and the same historical moment.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): That’s great. I know we have a lot of researchers and educators right here with us that will dig into some of those names. I love it.

Cierra Kaler-Jones (she/her): Yeah. I was trying to scribble down all of those names, and I hope that we all can just give librarians their flowers, too. I think about so many experiences going to the library and opening up new perspectives for me and new possibilities. I am just appreciative and grateful to you for lifting that up as part of this rich tradition and this legacy. On that note, Madeline Morgan once said, “Knowledge is only power if it’s put into action.” I love that quote. So, what lessons can we gain from how Madeline Morgan organized, and how does her story better help us understand how to build and struggle against current legislative attacks on Black education and Black history?

Michael Hines (he/him): I think the easiest answer, the most simple answer, is that it really highlights the power of teachers and of teacher networks like we’ve been talking about. This work that we’re doing here is a continuation of the things that people like Madeline Morgan were doing almost a century ago. So, if nothing else, I think we can be heartened by the fact that this is not the first time that we’ve seen this stuff.

Jesse, you were saying when we were talking about racist curricula that some of the things that were going on in the 1930s are really echoed in some of the things happening in Florida today. When you see slavery portrayed as something where enslaved people learned “valuable skills,” knowing that that’s not the first time, that this isn’t random, either. It’s not a mistake, it’s not random, it’s not just one sentence. It’s part of an attack that’s been ongoing for generations, for decades, as part of a historical narrative that’s been there for a long time, and that we have to fight back against and push back against. So I think drawing from history in that way is important.

I think another thing that really stood out for me is that better curriculum can’t be additive. It can’t be something that’s at the margins. The reason why Morgan’s curriculum didn’t take is because it didn’t replace what came before. It was too easy for policymakers to abandon it when the political winds shifted and when their priorities shifted, and she even saw that after the war. She worked for a bill in Illinois that would have codified Black history as a requirement for graduation in her home state, and, unfortunately, when that bill went to the House it was modified, the language was modified, and it went from a must to a may, or a must to a can if they want to. And we all know what happens after that, right? It makes it largely symbolic. It takes away any of the teeth. I think that this work that we’re doing has to be done from the ground up. It can’t be around the margins. We can’t nibble around the margins; we’ve got to uproot the curriculum and replace it from the ground up.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Well, thank you for doing all this research and letting us all in on this vital history. Like so many people here this evening, who are not just studying this history passively, but doing exactly what Madeline Morgan said in terms of putting it into action. There are people here not only teaching antiracist curriculum, but also part of the movement to teach truth and fight against these laws. I think we’re all stronger in this struggle now that we’ve learned this history, and I hope that everybody will go get this book immediately and read the details and really get to know Madeline Morgan in a way you can only do by reading this book. So, thanks so much for being with us this evening.

Michael Hines (he/him): Alright, thank you, too, and thanks to everybody who came out. I really appreciate the opportunity.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audiogram

In this audiogram, Michael Hines discusses “historians without portfolio” and the critical, often overlooked work of classroom teachers in the history of the Black education struggle.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

Books and Articles

|

In addition to A Worthy Piece of Work: The Untold Story of Madeline Morgan and the Fight for Black History in Schools, the following readings were referenced. Carter Reads the Newspaper a picture book by Deborah Hopkinson (Peachtree) African American History Reconsidered by Pero Gaglo Dagbovie (University of Illinois Press) Black Lives Matter at School: An Uprising for Educational Justice edited by Denisha Jones and Jesse Hagopian (Haymarket Books) Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865-1890 by Hilary Green (Fordham University Press) Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching by Jarvis R. Givens (Harvard University Press) Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad by Matthew Delmont (Viking). Share how you plan to use the book in the classroom and get a free book. Offer available while supplies last. Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC edited by Faith S. Holsaert, Martha Prescod Norman Noonan, Judy Richardson, Betty Garman Robinson, Jean Smith Young, and Dorothy M. Zellner (University of Illinois Press) The Lost Education of Horace Tate: Uncovering the Hidden Heroes Who Fought for Justice in Schools by Vanessa Siddle Walker (The New Press) The Mis-Education of the Negro by Carter G. Woodson (Penguin Group) Teaching for Black Lives co-edited by Dyan Watson, Jesse Hagopian, and Wayne Au (Rethinking Schools) Five Ways Textbooks Lie About Reconstruction by Mimi Eisen (an addendum to the Zinn Education Project report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle) |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

Participant Reflections

With more than 180 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 36% K–12 teachers, 28% teacher educators, and 7% historians.

Participants Dr. Candace Cofield (in Hayward, California) and LaShelle Ferguson (in Prince George’s County, Maryland) spoke briefly about the impact of being a part of a Teaching for Black Lives study group. Beyond shared education and experiences, Cofield noted, these study groups serve “as a supportive affinity space for us to keep our own wellness in mind as we do this work.”

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

How local history matters and the impact that it has on understanding at the national and global levels.

Knowing that this really is a battle to bring accuracy into the classroom, particularly in the face of so many states trying to whitewash history and rewrite the narratives. One of the teachers in our breakout group shared an activity he called “Bringers of Knowledge,” where he has students research different people and cultures and bring that information and share it with their peers. I think this would be an excellent thing to incorporate into my future ELA classroom.

A reminder about the importance of not letting Black studies or ethnic studies become supplemental. It’s too easy to brush aside and have it taken away.

The intercultural education movement was more or less disbanded with the rise of McCarthyism and fear of communism in the U.S.

The agency of Black educators pre-Brown v. Board.

Black history is available, if not always readily accessible. People can change how history plays out, even if it takes generations. Black history cannot be marginalized.

I learned just how long misrepresenting Black history has been going on in textbooks and curriculum.

I’m thinking about how resistance is teaching hard history.

This class emphasized the role of Black women classroom teachers as leaders in curricular change.

How much there is to learn and grow from Madeline Morgan’s life and work. Along with the reminder that she is one actor in a much bigger story about how and why we are able to teach what we teach.

What did you learn in your breakout room?

In group 8, we appreciated the concept of making sure everyone felt seen and how students responded when Madeline Morgan’s curriculum was implemented. Most of the attendees didn’t know much about Morgan’s contributions and loved the idea of incorporating it into their classroom.

Group 23 talked about racial literacy as a counter-hegemonic practice rooted in kinship/empathy that extends beyond the classroom.

We spoke about feeling angry about the whitewashing that occurs with textbook companies regarding the narratives of Black folks’ impact on and contributions to history. We discussed how much further we have to go, how we can use primary sources to educate, and how it empowers us to know that as educators we can disrupt this historic and current trend. As one member shared, we are “…leading a revolution.” It may start small with some educators on board at first at our schools, but we are hopeful. The Teaching for Black Lives study groups is a valuable, appreciative way to lead this revolution.

Group 6 was fantastic! Love that I am starting to recognize people from other T4BL and other Teaching for Black Lives classes.

Thanks to Valencia Abbott in room 13 and to the rest of our group for speaking to how we can get hope and strength from the stories of folks like Madeline Morgan. We so need that now.

What will you do with what you learned?

I will make sure to share the information that Black women, teachers, and librarians were doing this work long before and yet were not acknowledged. They are unsung heroes.

I am always looking for ways to unlearn my own inaccurate public school education and learn where and how it was incomplete, so I am better able to teach our current high school students. I want to facilitate a better future by opening eyes, minds, and hearts so they are empowered to lead us into the light.

I’m a social science specialist in Chicago Public Schools. I’ll share this story with others in my department and advocate that Madeline Morgan’s story be included in our district’s curriculum.

This class has helped put more resources in my toolbox.

I will bring this back to my Teaching for Black Lives study group and to my rural public charter school. Let’s get this information out there and ignite passion in my students.

I will share the knowledge and use it to further what I share with educators here in NYC as we struggle to establish Black history curricula here.

I loved the idea that there are so many women to lift up with their experiences. I am looking for any way to incorporate a wide variety of perspectives in all that I teach in first grade.

I can better inform students and point them in directions that will enable them to learn our full history and give them confidence to become their full, best selves.

I will keep striving to speak for all communities and keep learning correct information to teach history without it being whitewashed.

I will be sharing this information with teachers at my school and other schools in the district, and will work to get ZEP resources into as many hands as possible.

I think I will use this lesson to empower those in my classroom. Teaching them that they do not need professional credentials to be a storyteller and historian, and that they too can collect history and speak out.

Presenters

Michael Hines is an historian of U.S. education and an assistant professor of education at Stanford University. His work focuses on the educational activism of Black teachers, students, and communities during the Progressive Era (1890s–1940s). Besides his book, A Worthy Piece of Work, Dr. Hines has published articles and book chapters in the Journal of African American History, History of Education Quarterly, Review of Educational Research, and the Journal of the History Childhood and Youth, and in popular outlets including the Washington Post, Time magazine, and Chalkbeat.

Cierra Kaler-Jones serves as the first executive director of Rethinking Schools. Cierra is also on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project, which Rethinking Schools coordinates with Teaching for Change, and has hosted many of our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes. Cierra is a teacher, a dancer, a writer, and a researcher. She previously served as director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn